|

The Case of the Pope: Vatican Accountability for Human Rights Abuse

By Geoffrey Robertson

Church and State

January 7, 2015

http://churchandstate.org.uk/2010/11/can-the-pope-be-sued/

|

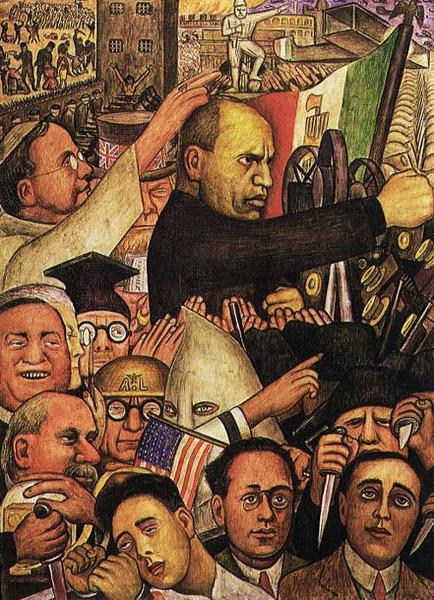

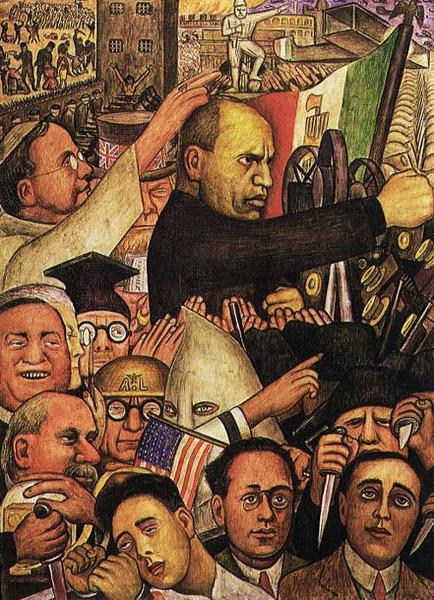

| Diego Rivera captures a truth about the Lateran Treaty. The pro-Fascist Pope Pius XI blesses (with fingers crossed) the demagogue Mussolini, having stayed silent when his death squad murdered the courageous democrat MP Matteotti |

Exclusive excerpt from Geoffrey Robertson’s book, The Case of the Pope: Vatican Accountability for Human Rights Abuse (published by Penguin Books in 2010). This book delivers a devastating indictment of the way the Vatican has run a secret legal system that shields paedophile priests from criminal trial around the world.

Is the Pope morally or legally responsible for the negligence that has allowed so many terrible crimes to go unpunished? Should he and his seat of power, the Holy See, continue to enjoy an immunity that places them above the law?

Geoffrey Robertson QC, a distinguished human rights lawyer and judge, evinces a deep respect for the good works of Catholics and their church. But, he argues, unless Pope Benedict XVI can divest himself of the beguilements of statehood and devotion to obsolescent Canon law, the Vatican will remain a serious enemy to the advance of human rights.

In the exclusive excerpt below – the first six pages of Chapter 10, “Can the Pope be Sued?” – Robertson reveals that unless the Vatican confronts its history of protecting paedophile priests and abandons its claim to deal with them under Canon Law, then its leader might well be sued for damages or end up as the subject of investigation by the prosecutor at an international court.

Geoffrey Robertson QC is founder and head of Doughty Street Chambers. He is a ‘distinguished jurist’ member of the United Nations Justice Council, having served as the first President of the Special Court in Sierra Leone. He has argued many landmark cases in media, constitutional and criminal law in the European Court of Human Rights, the House of Lords, the Privy Council and Commonwealth courts. He has recently appeared in the Court of Final Appeal for Hong Kong, the Supreme Court of Malaysia, the Fiji Court of Appeal, the High Court of Australia and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes.

His books include Crimes Against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice; Media Law; Freedom, the Individual and the Law; a memoir The Justice Game; and The Tyrannicide Brief, which tells the dramatic story of how Cromwell’s lawyers challenged the monarchy.

10. Can the Pope be Sued?

“The bishop of the Roman church, in whom continues the office given by the Lord uniquely to Peter, the first of the Apostles, and to be transmitted to his successors, is the Head of the College of Bishops, the Vicar of Christ and the pastor of the universal church on earth. By virtue of his office he possesses supreme, full, immediate and universal ordinary power in the church, which he is always able to exercise freely.”

Canon 331

|

215. |

The act of sexually abusing a child is not only a crime – it is a tort (a civil wrong) of assault and battery to the person occasioning a physical or psychological injury for which the victim can sue to obtain financial compensation. The direct perpetrator, if a priest who has by definition taken a vow of poverty, will rarely be in a position to meet a damages award, but in most cases his employer – the bishop or diocese for which he works – will be a ‘joint tortfeasor’ and hence vicariously liable because the wrongful act was committed in the course of employment. Bishops may, alternatively, be held directly responsible for their negligent failure to supervise the priest or to take sufficient care of the children in his charge, for example by ignoring their complaints or providing no effective investigation. In most cases, therefore, plaintiffs will have no need to look to Rome to find a defendant with deep pockets: usually dioceses have insurers who will take over civil actions by subrogation, and decide whether to fight or settle them. The courts in common law countries have developed rules for employers’ liability for sexual assaults committed by employees, generally finding vicarious liability where the wrongful act by an employee is connected with his employment, as in most clerical abuse cases.[1] There are, however, exceptional cases: in the US, dioceses are corporate entities which makes them easy to sue but unviable as defendants if they declare themselves bankrupt. And in some common law countries the Catholic Church remains an unincorporated association which does not exist as a juristic entity and cannot be sued in its own name – so unless the plaintiff can identify the officials who exercised an active or managerial role and can therefore be held personally liable, his action will fail.[2] There are, in other words, meritorious claims which cannot for technical or legal reasons be met by local church defendants, so some plaintiffs have good reason to consider taking action against the Holy See or the Pope. |

|

216. |

There is nothing objectionable, in principle or in justice, about seeking redress from an organization (or its leader) that is ultimately responsible for the damage: legal actions serve not only to compensate the injured, but to provide the best incentive for the organization to exert its powers of control to prevent similar harm from being done in future to others. The doctrine of respondeat superior, by which an employer is held responsible for actions of agents and employees, irrespective of any direct authorization, has the policy rationale of encouraging greater care in their selection and control. The Pope appoints and dismisses bishops, and is ultimately responsible for disciplining priests: Canon 331 of the Code of Canon Law gives him supreme power in the church. The Holy See has had no difficulty in calling clergy to account for errors of doctrine or morality, no matter where in the world they are based, through its moral and legal authority over subordinates in Catholic religious orders that are bound by obedience to the Pope ‘as their superior’ (Canon 590). It follows that allowing plaintiffs to sue the Holy See for clerical sex abuse ‘could have a significant policy effect by encouraging better safeguards and more stringent oversight at the highest level of the church’s administration … and emphasize cooperation with law enforcement, while requiring church leaders to account for their effectiveness in overseeing their personnel and protecting the members of the faithful entrusted to their care’.[3] Given these obvious public interests, is there any good reason why, in appropriate cases, plaintiffs should be disbarred from suing the head or governing body of the Catholic Church? |

|

217. |

The first hurdle for them to surmount is state immunity, which protects against civil suit as well as criminal action. In the case of Doe v Roman Catholic Diocese of Galveston-Houston and Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, the second-named defendant had become Pope Benedict XVI by the time the action was heard. As Cardinal Ratzinger, he was alleged to have approved the Crimen system of concealment: his 2001 letter, so the plaintiffs pleaded, ‘is conspiratorial on its face in that it reminds the archdiocese that clerical sexual assault of minors is subject to exclusive clerical control and pontifical secrecy’.[4] However, the US State Department filed a ‘suggestion of immunity’ under the hand of Bush lawyer John Bellinger III which recited that ‘the apostolic nunciature has formally requested that the government of the US take all steps necessary to have this action against Pope Benedict XVI dismissed’.[5] American courts deferentially treat such State Department ‘suggestions’ as diktats, and the case was dismissed on the Bellinger certification that the Pope was ‘the sitting Head of State of the Holy See … a foreign state’. There was no argument about whether it was a state, because the government’s ‘suggestion’ was treated as conclusive. Courts in some other countries are not prepared to defer to the Executive to this extent and might hear argument on whether the Holy See satisfies the Montevideo criteria. In Britain, although Section 21 of the State Immunity Act provides that a ‘certificate of statehood’ from the Foreign Secretary shall be ‘conclusive evidence’ of whether a country is a state,[6] in the case of the Holy See the courts would probably be prepared to examine the correctness or at least the rationality of the minister’s decision to grant the certificate, in light of international law. As Law Woolf pointed out in the Pitcairn Island case,

today it can no longer be taken for granted that the courts will accept that there is any action on the part of the Crown that is not open to any form of review by the courts if a proper foundation for the review is established.[7]

But if the Holy See is a state, the Pontiff cannot be brought before any civil court, even for wrongs that he committed when he was Cardinal Ratzinger.[8] Were he to resign, of course, he could be made a defendant – the case of ex-King Farouk (who was held liable for his mistress’s Paris debts for Dior dresses after he was deposed) shows there is nothing so ‘ex’ as an ex head of state. An ex-Pope, however, is an oxymoron.[9]

|

|

218. |

The Holy See is a different matter. Even if it succeeds in establishing that it is a state, it will not have complete immunity from civil process. State immunity, after all, is a hangover from centuries past, where great sovereign nations regarded themselves as equals: their ‘comity’ would be upset if they permitted their courts to entertain actions against other nations. But when states and their nationalized corporations began to engage in international ventures which could do serious damage by breaching contracts or causing injuries, this had to change, and most countries now have national laws that restrict the immunities of states that engage in commerce or undertake activities that, through negligence, cause personal injury to individuals in the country in question. The European Convention on State Immunity reflects these exceptions, and in the UK the State Immunity Act (SIA) of 1978 and in the US the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) incorporates them in broad terms. There is an exception for states that engage in commerce, but it is difficult (although not impossible) to argue that the Holy See engages in commercial transactions with its dioceses: it could be said to supply them with organizational and doctrinal services in return for financial contributions (for example ‘St Peter’s pence’). Where it is more clearly vulnerable to immunity loss when it is made a defendant to actions for negligence; for example ‘for proceedings in respect of … personal injury … caused by an act or omission in the United Kingdom’ (SIA s 5). Or when ‘money damages are sought … for personal injury … occurring in the US and caused by the tortious act or omission of that foreign state or any official or employee of that foreign state while acting within the scope of his or her employment’.[10] Other advanced nations restrict immunity in similar terms, so there would be no immediate bar to a civil action against the Holy See in relation to child sex abuse committed by a priest employed by the Catholic Church in the country where the action was brought, so long as a casual connection could be plausibly alleged with negligent orders or directives or decisions issued from the Vatican. |

|

219. |

As in all tort claims, much would depend on the particular facts. The Vatican obviously does not direct priests to offend, or approve in any way of sex abuse. The cases brought against it in the US by victims of re-offending priests have been based on the theory that the abuse would not have happened had the Vatican directed its bishops to inform law enforcement authorities of the evidence of the original abuse, or had not ordered or approved reassignment to other parishes or to other countries – all being directives given with foresight of the risk that the priest will re-offend. These decisions are taken in the Vatican, outside the country where the claim is brought, and to succeed against the Holy See the plaintiff has to show that the directive was communicated to and complied with by the local bishop.[11] An alternative approach has been to argue that bishops are employees of the Holy See, acting within the scope of their employment and under instructions from the Holy See when they negligently failed to warn parishioners about paedophile priests and failed to report allegations of child abuse to police. |

|

220. |

The English Court of Appeal has recently cut through some of these problems by asking whether there was a sufficiently close connection between the defendant’s employment as a priest and the sex abuse he inflicted on a boy to make it ‘fair and just’ to impose vicarious liability and make the church pay. This was a strong case because the victim was not a Catholic, but was picked up whilst admiring the priest’s sports car. Nonetheless, the Court held that his church was liable: a priest has ‘a special role, which involves trust and responsibility in a more general way even than a teacher, a doctor or a nurse. He is, in a sense, never off duty.’[12] His clerical garb ‘set the scene’ by emitting a moral authority that can bewitch a small boy. |

|

221. |

The only case that has as yet reached the US Supreme Court – where in 2010 the Vatican suffered a serious setback – is Doe v Holy See.[13] The plaintiff had been molested at the age of 15 by a priest at a monastery in Portland. Ten years previously the same priest had admitted to sexually abusing a child at a church in Ireland, so he had been furtively trafficked to work as a counsellor at a boys’ high school in Chicago, where (as he later admitted), ‘temptation to molest was maximized’. After three victims complained, he was sent to Portland where the plaintiff became his next victim. The case against the Holy See was based on its controlling power over the Catholic Church, its process of appointment and removal of bishops and through them its responsibility for disciplining priests. In this case, despite knowing of the priest’s dangerous propensities to abuse children, it negligently placed him, time and again, in a position to do so, and negligently failed to warn those coming into contact with him, including the plaintiff and his family, and negligently failed to supervise him. The Court rejected the Holy See’s technical defence that its conduct did not occur in the United States, on the basis that it was sufficient that the injury and some of the conduct alleged to be negligent took place there, even if other aspects of the negligent conduct took place at the Vatican. The state of Oregon, where the action was brought, had an extended law of employer liability which covered crimes committed by an employee as a result of being given the opportunity to commit them by his employment, and the Holy See was potentially liable on the basis that ‘an employer who has knowledge of an employee’s predilection to sexually abuse young boys unreasonably creates a foreseeable risk by allowing the employee uninhibited access to young boys’. |

|

222. |

The Vatican, pursuant to its strategy of avoiding trial at all costs, took an appeal against this ruling all the way to the Supreme Court, where it had the support of the Obama administration in an amicus brief filed by Solicitor-General Harold Koh, who made some inconsequential submissions about Oregon law and the FSIA which did nor persuade the Court. He did confirm that the Holy See ‘is recognized as a foreign sovereign by the US’ – an indication that, like the Bush administration, the Obama White House will support the Pope’s claim to immunity.[14] This case, however, proceeded under the FSIA exception to immunity, and the Supreme Court rejected the Vatican’s request to review the decision of the Court below. In practical terms, this means that the Vatican tactic has misfired and it may have to go to trial, or at least make some evidential disclosure about CDF treatment of paedophile priests and perhaps even permit the Pope (although it is certain to proffer only a monsignor) to answer questions on oath in a recorded deposition. |

Notes

[1] See Bazley v Curry (1999) 174 DLR (4th) 45 (Supreme Court of Canada); Lister v Hesley Hall [2002] I AC 215 (UK House of Lords) and NSW v Lepore (2003) 195 ALR 412 (High Court of Australia), discussed in Simon Deakin, Angus Johnson and Basil Markesinis, Tort Law (5th edn, OUP, Oxford, 2003), 593-5. In Maga v Trustees of Birmingham Catholic Archdiocese [2010] EWCA Civ 256, the English Court of Appeal gave broad scope to the requirement of a ‘connection’ between a priest and the church that is necessary to support a child sex abuse claim.

[2] See Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church v Ellis (2007) NSWCA 117, where a body representing members of the Catholic Church could not be made liable for actions by an assistant parish priest. This was a bad case where the victim had complained to the priest’s superior who, without his knowledge, arranged for him to be confronted by his abuser to ‘work things out’. ‘It is rather chilling to contemplate’ said the judge, that the superior might have been another sex abuser. See first instance decision Ellis v Pell [2006] NSWSC 109, para 90.

[3] Lucian C. Martinez, ‘Sovereign Impunity: Does the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act Bar Lawsuits Against the Holy See in Clerical Sexual abuse Cases?’ (2008), 44 Texas International Law Journal, 123, 144.

[4] Roman Catholic Diocese of Galvarston-Houston 408 F Supp 2d at 276.

[5] Letter, 2 August 2005, John Bellinger III (Legal Advisor to the State Department) to Peter Keisler (Assistant Attorney General, US Department of Justice).

[6] This ministerial certificate is conclusive only in civil proceedings. It might be introduced in criminal proceedings, where it would be ‘significant’ but not conclusive: Alamieyeseigha v CPS [2005] EWHC 2104.

[7] Christian v R [2007] 2 AC 400 at para 33, per Lord Woolf. The attack would have to be based on the irrationality of certifying the Holy See as a state. The ECHR has held, albeit by 9:8, that although state immunity denies access to justice (a prima facie breach of Article 6), it is within the ‘margin of appreciation’ for a state (the UK) to extend it even when the plaintiffs were trying to sue over a crime against humanity (torture inflicted by officials of Saudi Arabia). See Al-Adsani v UK (2001) EHRR 273 and David McClean and Kisch Beevers, Morris’s Conflict of Laws (7th edn, Sweet & Maxwell, London, 2008) 153.

[8] This was the conclusion of Justice David Hunt in a curious libel action brought by a priest against both his bishop and Pope John Paul II for a statement by his diocese that he was mentally deranged when he attacked politicians in a sermon. It was not disputed by the plaintiff that the Pope was head of state, so the judge applied the rule that he could not be sued in New South Wales unless he consented: Wilkins v Jennings and Pope John Paul II (1985) ATR 68-754. Ironically, sixteen years later, it was Judge David Hunt, sitting as a judge of the ICTY, who issued the indictment against Slobodan Milosevic, a sitting head of state, for crimes against humanity.

[9] The last Pope to abdicate was Gregory XII, in 1415.

[10] 28 USC s 1605(a)(5) cite King Farouk case

[11] The alternative basis for liability would be to invite the Court to find that the abusive priest was directly employed by the Holy See, which would have made him vicariously liable for the assaults. See Doe v Holy See 434 F Supp 2d at 949: O’Bryan v Holy See 471 at Supp 2d at 291; Melanie Black, ‘The Unusual Sovereign State: FSIA and Litigation against the Holy See for its Role in the Global Priest Sexual Abuse Scandal’ (2009), 27(2) Wisconsin International Law Journal, 299.

[12] Maga v Trustees of Birmingham Catholic Archdiocese [2010] EWCA Civ 256, per Neuberger MR.

[13] John Doe v Holy See, US District Court, Oregon, Judge Mosman, 7 June 2006, and see Doe v Holy See, US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, No. 06-35563 and ‘US Rules that Victims Can Sue the Vatican’, The Times, 29 June 2010.

[14] Holy See (Petitioner) v John V Doe, Supreme Court Case No. 09-I, brief for the United States as amicus curiae, filed by Solicitor-General Koh, May 2010, 3-4.

|