|

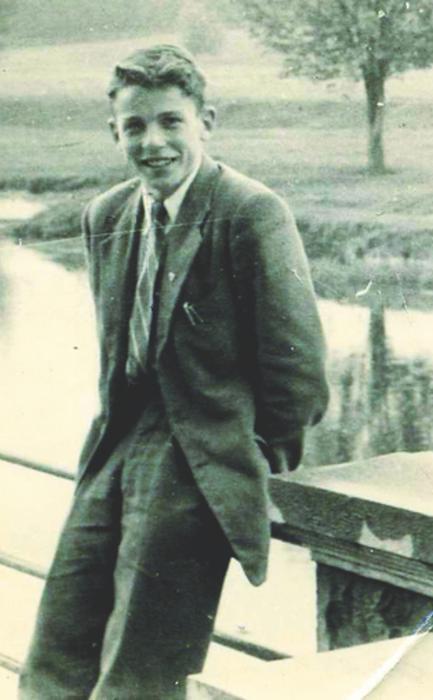

Local View: Retired Duluthian still healing after abuse, life of shame and guilt

By Damien Cronin

I had just turned 13 in 1954 when I started at Dominican College Newbridge, a residential Catholic high school for boys in Ireland. I had grown up in Carrick-on Shannon, a small town in the Midlands, and this was my first time away from home and family.In October or November, I recall, I was told a priest wanted to see me in his office. He was waiting for me and closed the door behind me. He told me he had heard that too many of the new students were goofing off and that I was a main offender. He told me to drop my pants. He then put me across his knees and gave me a terrible beating. I’m convinced he meant to hurt me. Next he stood me up in front of him, and he molested me. I was shocked and in pain. He told me to pull up my pants and return to study hall. He warned me not to tell anyone what happened or he would expel me and call my parents to pick me up; I would have to leave in total disgrace, he said. I was so ashamed. It was all my fault. I believed everyone in the school, faculty and students alike, knew or soon would know what happened. I clearly was a bad kid. The priest said so. The baddest of the bad, he said. I believed him. And it became my personal definition. I was totally unworthy of anyone’s friendship or love or caring. I had become a shame-based child.Within a few months I forgot about the beating and molestation. I did not know the psychological term for this, repression. But I clearly had unknowingly repressed all memories of the abuse. It was a way of subconsciously protecting myself from the awful memories. A year later I had this priest as an English teacher, and two years after that he was coach of my rugby team. I was clueless about what he had done to me. But shame was not just an abstract idea running around in my brain. I lived it every day. I was fearful of others. I blamed myself for anything that went wrong. I wanted friends, love and attention, but I never trusted it when it was offered because I knew that as soon as anybody got to know me they would want nothing to do with me. That was my truth. It was who I really was. And it was never questioned. I put myself on a mission to not make mistakes and to excel at everything. Then I could rid myself of the black shame. I did well academically and in sports at Newbridge. But I was still a lost kid who did not know he was lost. Neither did anybody else. Struggling with my shame When I was 17, I decided to become a Dominican priest. I remember thinking that being a Catholic priest was an honorable profession, that people would respect me, and it would offer me many opportunities to help others. What I didn’t realize was that the motivation behind this decision was really to remove my shame. In 1959, still in Ireland, I joined the Dominican Order as a novice. From the beginning it was not a good fit. The daily routine of praying, chanting, meditating and silence was so difficult. But being a good Irish Catholic boy, there was no quitting. That would have confirmed my unworthiness. I was on another mission — my own mission impossible. In 1965, I was among a group of six Irish Dominican students sent to the Dominican House of studies in Dubuque, Iowa, to study for a master’s degree in theology. I loved it. In 1966, I was ordained a Dominican priest in Dublin, and afterward I returned to Iowa to continue my studies. While there, I began another master’s degree, and that was when I first had doubts about remaining a priest. Scary and persistent, these thoughts forced me to take perhaps the first real look at myself and where I was going. I shared my doubts with many American Dominicans, and they were understanding and supportive. They told me it had to be my decision. In Ireland two years later, my brothers and sister were great, too: loving, understanding and very supportive. But it was a different story when I confided my doubts to my brother Irish Dominicans. Their responses included, “Please leave; we have nothing more to say to each other,” and, “You are possessed by the devil and you should go to a Cistercian monastery and have the devils cast out.” Probably the worst was when an Irish Dominican priest barged into my room and tore into me for about 30 minutes and called me every name he could think of and ended up telling me I was an absolute disgrace and an embarrassment to the Irish Dominicans. My parents, too, immediately became very angry and made it clear I no longer was welcome in their home. I had confided my doubts to people I loved and respected and very much needed. But I let them down, and it was all my doing and my fault. I was beaten up, thrown away and penniless. My guilt and all the rest I added to my shame bucket. Despite the harsh pressures to the contrary, I decided in 1969 that I no longer should remain a priest. Golden time in Duluth I knew there would be no way I could live in Ireland as a layman. The American Dominicans in Dubuque kindly took me in while I got back on my feet. They were aware of my situation and were supportive and very kind. I spent most of my time while there applying for scholarships and admission to graduate school to get a master’s in psychology. I wanted to teach psychology and be a counselor at the college level. I returned to college in Iowa but flunked out after a year. In 1970, I was accepted into the University of Minnesota Duluth’s graduate program in counseling. I supported myself in Duluth by taking any job I could find: construction, roofing, cleaning restaurants and bartending were among them. I also lived for a year in a funeral home. My job there was to pick up dead people from the local hospitals and morgue. Not the most pleasant job but it did keep a roof over my head. I finished my master’s in 1972 and was offered a full-time job at UMD, teaching psychology and counseling. It was then that I got married. I was on my way again and over the moon with joy and confidence. It was a golden time for me. But within three years I was diagnosed with alcoholism, and my marriage ended. In treatment I learned a lot about myself and came to believe my shame and depression were caused by my disease, and that as long as I stayed sober the symptoms would disappear. In reality, my drug use was a symptom of my deep-felt shame, not a cause of it. Sober (and for 39 years now), I remarried. But that marriage also failed. My relationships were doomed, I know now, by the negative baggage I carried inside of me from the abuse. In 1988 I became head of the counseling office at UMD. I enjoyed teaching and counseling. I counseled hundreds of victims of every kind of abuse, unaware through every session that two abuse victims were always present. Teaching and counseling were the most meaningful and satisfying things I ever did. But there were times when I helped a client feel better and more hopeful that, while I was delighted for them, I also was envious. I knew I could never have what they had. That’s what my shame and depression kept telling me. Facing my abuser In 2003, I was diagnosed with clinical depression. Three years later while in Ireland visiting family, my abuser walked by unexpectedly. More than 50 years had passed since I had seen him. Instantly I wanted to get in his face and call him every name I could think of. I was shocked at my reaction and could barely control my urge to utterly humiliate him. I had no idea what this was all about, and even after thinking about it for months I was still clueless. Less than three years ago, in 2012, an Irish friend mentioned in an email that my abuser died. Within minutes all the ugly memories came flooding back — the summons to his office, the terrible beating, the molestation and the stern warning. I was devastated by the ugly, heart-scalding memories. I finally recalled what happened to me. Eventually I could cry for this innocent child. Two months later I contacted the Irish Dominicans, told them about the physical and sexual abuse, and started therapy that would last for two years. It was a tough slog, meeting weekly with a therapist, but it worked. I was able to shed much of my shame and depression after carrying them for 60 years. I met with the head of the Irish Dominicans in Dublin in April 2014 and told him my unvarnished story. He said it was an ugly story. It was a golden day for me to be heard and believed, even though there was no evidence to back me up and it had happened so long ago. I gave back to him the shame and depression I had carried for six decades. It didn’t belong to me. It belonged with the Irish Dominicans. I have forgiven most of my abusers and believe eventually I will be able to forgive all of them. Today I am a happily retired college professor and counselor, grandfather, avid gardener, nature lover, photographer and writer. I am healing, fun-loving, healthy and happy. I have so many to thank for helping me on my journey and finding my way back. I am so grateful to God who never gave up on me, to my brothers and sister and nephew and family in Ireland, to the American Dominicans, to my therapist, to a wonderful organization in Ireland called “Towards Healing,” to many, many good friends on both sides of the Atlantic, and to Father Eric, pastor of St Benedict’s Parish in Duluth, who welcomed me back to the Catholic Church. I thank them all. Contact: damiencronin@charter.net

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.