|

Debate Over the Rabbi and the Sauna

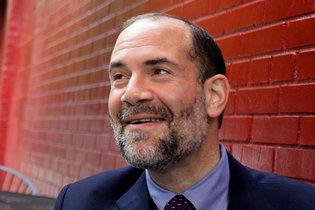

By Andy Newman And Sharon Otterman

For years, Rabbi Jonathan Rosenblatt, the leader of an affluent Modern Orthodox synagogue in the Bronx, did something unusual with the boys in his congregation. He took them, some as young as 12, to the gym to play squash or racquetball, then showered beside them and took them into the sauna, where — often naked, and with them often naked — he engaged the boys in searching conversations about their lives, problems and faith. Some liked talking to the rabbi. But others felt uncomfortable. At the time, the late 1980s, people at Rabbi Rosenblatt’s synagogue, the Riverdale Jewish Center, quietly urged him to stop. He said he would. They believe he eventually did. And because the rabbi was not accused of sexual misconduct, and because this was a time less attuned to issues of clerical impropriety, not much more came of it. As Rabbi Rosenblatt, an accomplished scholar who married into rabbinical royalty, grew to be one of New York City’s most prominent Orthodox leaders, he took older squash partners to the sauna: college students, rabbinical interns, young men from his congregation. Many enjoyed the sauna discussions. Rabbi Rosenblatt acquired a reputation as a great mentor. He told several people the sauna talks — in the Jewish tradition of men enjoying fellowship in the shvitz, or steam baths — were a key to his success. But some people objected to the practice. They said the rabbi was using his authority and position to see his disciples naked. Major Jewish institutions told Rabbi Rosenblatt that inviting his charges to the sauna was not appropriate rabbinical conduct. The nation’s leading seminary for Orthodox rabbis stopped placing interns with him. The Rabbinical Council of America, which oversees American Orthodox rabbis, later made him agree to a plan to limit his activities with his own congregation. Because these steps were taken behind closed doors, the broader community did not know about them. But last fall, decades after the first complaints, a man whom Rabbi Rosenblatt once took to the sauna learned that the rabbi had spoken to sixth graders at the school the man’s son attends. The father posted an email to a Jewish discussion group with about 500 members, who turned out to include at least six veterans of the sauna sessions. Their accounts, along with others that have emerged, paint a disturbing picture. According to the boys involved, who now are grown, the rabbi openly gawked at a naked 12-year-old. He invited a 15-year-old over for intimate nighttime conversations, during which he frequently put his hand on the boy’s leg. He invited himself into a 17-year-old’s living room and tried repeatedly to persuade him to change into a bathrobe. The email thread — private, but later shared in part with a reporter — focused new attention on Rabbi Rosenblatt and raised questions that linger still: What lines did Rabbi Rosenblatt’s behavior cross, if any? Did institutions that dealt with him endanger anyone by acting so quietly? And what should a community do with a religious leader — one beloved by many — whose conduct seems troubling? Rabbi Rosenblatt did not respond to numerous requests for interviews. Seven past and present officials of his synagogue also declined to be interviewed, did not respond to requests or declined to speak for publication about Rabbi Rosenblatt and the sauna talks. The rabbinical council said in a statement, “The leadership of the synagogue has assured the R.C.A. that Rabbi Rosenblatt has acted in accord with the plan” — the plan limiting his interactions with his congregation. Rabbi Rosenblatt, now 58, with a silver beard and a commanding presence, remains an important figure in Modern Orthodoxy. He was considered for the post of chief rabbi of Britain several years ago, is a visiting scholar at Harvard this year and is often invited to speak to and teach young people. His case is hardly the typical stuff of clerical scandal; parsing it is an exercise in ambiguity. From a legal point of view, said Linda Fairstein, the novelist and former sex-crime prosecutor, similar conduct could be construed as endangering the welfare of a minor, a misdemeanor that includes knowingly acting “in a manner likely to be injurious to the physical, mental or moral welfare of a child less than 17 years old.” “I see it as entirely inappropriate behavior for any adult mentoring kids,” Ms. Fairstein said. From a religious standpoint, said Lawrence Schiffman, a professor of Judaic studies at New York University, the Talmud does not specifically forbid a rabbi from appearing naked before his disciples. “But happening to see someone in the shower or bath is a very different thing from hanging out and socializing with no clothes on,” he said. “That is not exactly a Jewish way of doing business.” Jonathan Rosenblatt was 28 or 29 years old in 1985 when he assumed leadership of the Riverdale Jewish Center, an angular structure of glass and concrete and tawny brick on a broad avenue. A Baltimore native with a master’s degree in comparative literature, Rabbi Rosenblatt is a great-grandson of a famed cantor, Yossele Rosenblatt, known as the Jewish Caruso. His wife is descended from both Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, a giant in modern American Orthodox Judaism, and from the Twersky Hasidic dynasty. Very soon, the new rabbi began inviting the local boys to gyms in the area. “It was sort of a rite of passage in Riverdale,” recalled one man, now in his 40s, who, like almost everyone else who spoke about Rabbi Rosenblatt and the sauna, asked to be anonymous for fear of professional or community repercussions. “Pretty much everyone I know that was of that age, you played racquetball with Rabbi Rosenblatt.” The man recalled that the rabbi paused to take in the sight of him naked. “In the shower, and as I got into the tub, I remember him gawking,” he said. He was 12 at the time. Parents began to talk to one another, and Sura Jeselsohn, a synagogue member with a penchant for note-taking, started a journal. On Nov. 29, 1988, she wrote, she dropped in on Rabbi Rosenblatt to share her worries and those of friends. “He was very calm and said that he had agreed to stop taking the kids to the shvitz,” she wrote, “but it was quite clear that he could not see what kind of judgment error this was. He kept trying to tell me that he found it ‘part of a package’ to achieve closeness with these kids.” The rabbi did not appear to have stopped in any case. Another man said Rabbi Rosenblatt took him to the sauna and hot tub more than a dozen times from 1986, when he was 13, until about 1993. The nudity, he said, always made him uncomfortable. “We’d be 15 minutes in the shower, then 15 minutes in the sauna, then 15 minutes in the hot tub,” he said. “There was no rush.” The conversations in the sauna and tub were wide-ranging. Sometimes the rabbi would compliment the boy’s athleticism. Sometimes they would talk about the boy’s conflicts with his parents. The rabbi, the man said, would usually buy him a soft drink at the end of the session. “I remember focusing and fixating on the soda I’d get at the end,” he said. Another former congregation member said that at the ritual immersion bath known as the mikvah, when he was about 15, “I remember getting out of the water and him watching me.” He asked the rabbi why. “He said, ‘I had to make sure that the whole body went underneath,’ ” the man recalled. “I just remember that as being so wrong.” Rabbi Rosenblatt, the man said, often had him over to his house in the evening to chat. “Let’s say I was talking about an issue in my life — when you’re 15 or 16 there’s so much going on,” the man said. “You’re sitting next to him, and he had this way of talking to you and at the same time putting his hand on you to console you.” The routine was always the same: “Always the hand on the shoulder or the leg, always the hand touching some part of your body.” The man said the rabbi never touched his genitals. The rabbi’s touch “was very seductive and it was very manipulative in a way,” the man said. Some who were older when they went to the sauna found the nudity only a minor annoyance. “I never liked that part of it,” said one man who was about 18 when the rabbi took him to the gym. “But to me it was an add-on to the squash, which I did enjoy. The concept of spending time one-on-one with the rabbi of the community for me was a positive.” Ms. Jeselsohn’s notes portray synagogue members and officials who were struggling to deal with Rabbi Rosenblatt but fearful of smearing his reputation or bringing shame on the synagogue. In 1989, she urged Marvin Hochberg, then the synagogue’s president, to have Rabbi Rosenblatt get counseling. Mr. Hochberg told her there was no need to involve “outsiders,” she wrote. “The strange thing is that he kept saying, ‘The rabbi promised, the rabbi promised,’ and that hardly sounded like an appropriate professional way to deal with it,” Ms. Jeselsohn wrote. Mr. Hochberg died in 2007. Ms. Jeselsohn’s journals end in 1990, when complaints tapered off. But through the 1990s, Rabbi Rosenblatt often took young guests to a gym at Columbia University, where he was earning a doctorate in British literature. Around 2002, several Columbia graduate students who attended an Orthodox synagogue near campus complained about Rabbi Rosenblatt’s sauna invitations, said a former official of that synagogue. Rabbi Rosenblatt promised the synagogue’s rabbi that he would stop taking Columbia students to the sauna, the official said. As time went on, Rabbi Rosenblatt became known as a trainer of fledgling rabbis, many of whom went on to prominent positions. He combined an attentive personal style with the pedigree and connections that could launch a career. The squash-and-shvitz sessions were a well-known part of his process. “I knew a lot of people who made the decision to be a rabbi based on his intense mentorship, which included sessions in the shvitz,” said a man who added that Rabbi Rosenblatt told him after a trip to the sauna that he would be a good fit for his synagogue’s internship program. Rabbi Rosenblatt regularly employed rabbinical interns from his alma mater, Yeshiva University, whose seminary is the nation’s largest for Modern Orthodox rabbis. But some Yeshiva alumni found the link between going to the shvitz with the rabbi and advancing professionally to be uncomfortable. “I avoided pursuing opportunities to learn from him and to be mentored by him,” said one graduate who is now a practicing rabbi. “I thought it was inappropriate for a leader to be putting students in that position, so I just stayed away.” Eventually, someone complained: Yeshiva University said in a statement last month that after “particular allegations” of “inappropriate behavior” arose, it had contacted the Rabbinical Council of America. The council brought in a psychiatrist, who reported that the rabbi “did not represent a danger to young men in that no physical boundaries had been crossed, or no inappropriate physical boundaries anyway,” said Rabbi Basil Herring, who was then the council’s executive vice president. Rabbi Herring said Rabbi Rosenblatt had agreed to stop taking Yeshiva interns to the sauna. Yeshiva University said it “discontinued sending interns to that synagogue,” but continued to allow students to “independently elect to pursue an internship” with Rabbi Rosenblatt. And they do: Since 2012, he has had at least six interns from Yeshiva. Two of his recent interns said they had not been invited to the sauna by Rabbi Rosenblatt. In about 2008, still bothered by the rabbi’s conduct, Ms. Jeselsohn contacted Rabbi Herring, who she said told her that Rabbi Rosenblatt was under the council’s psychological supervision. Sauna talks continued, though. Around 2010, Rabbi Rosenblatt befriended a married member of his congregation who was in his early 20s and took him to play squash, the man said. After the game, as they sat wrapped in towels in the steam, Rabbi Rosenblatt urged the man to talk about anything that was on his mind, including “marital issues.” The conversation grew halting. Then the rabbi said to the man, “You know, I’ve had my eye on you since” — and named the program where the rabbi first saw the man when he was about 15. “I’m thinking, ‘What the hell do I say back to that?’ ” the man recalled. He has since left the congregation. In December 2011, Rabbi Herring said — three years after Ms. Jeselsohn’s complaints — Rabbi Rosenblatt reached an agreement with the council to stop taking his congregants to the sauna. It was one of the rabbi’s former squash partners who started the most recent discussion. Yehuda Kurtzer, the head of a Jewish research center, was a 19-year-old Columbia student around 1997 when Rabbi Rosenblatt invited him to play squash. Mr. Kurtzer was “horrified and embarrassed” when the respected rabbi stripped and invited him into the sauna, and further troubled to learn that it was a standard invitation from the rabbi. Last October, Mr. Kurtzer read that the rabbi had just spoken at Salanter Akiba Riverdale Academy, a Jewish day school that Mr. Kurtzer’s son attends. Mr. Kurtzer complained to the school principal. And he posted an essay to the email list of the Wexner Foundation, a Jewish leadership group, asking, “What should I and we do about this rabbi in question?” The list was flooded with responses. A small number defended Rabbi Rosenblatt, but the vast majority condemned his conduct, Mr. Kurtzer said. And five men described sauna experiences they had found unsettling to varying degrees. One of them was the man for whom Rabbi Rosenblatt had bought sodas after each session. A sixth man wrote of an encounter with Rabbi Rosenblatt when he was 17, in 1988. He had felt sick after school the day he was to meet the rabbi, so the rabbi offered him a ride home. “We had a great conversation in the car, so much so that I still remember some of what he said,” the man wrote. Then the rabbi invited himself in. “When we got inside — he and I alone in a big house — he immediately asked me, ‘Would you like to change into a bathrobe? Sometimes if you’re sick it’s good to wear something comfortable,’ ” the man wrote. “I demurred, but in the span of a few minutes he asked me 3-4 times to change into a bathrobe.” One man who went to the sauna with the rabbi several times wrote that he had shrugged off his discomfort with the nudity until reading the email thread “with mounting disquiet and recognition.” Among his 20-something peers at the synagogue, the man wrote, being invited for a squash match with the charismatic rabbi “was seen almost as a mark of honor.” Many of them, he said, “just considered it to be the rabbi’s own personal shtick, without imputing any sinister motives.” “But I imagine,” the man continued, “that if you asked these same people in the abstract, what their thoughts would be about a rabbi who maneuvered himself into situations where he could see his congregants naked on a regular basis, none of them would hesitate about condemning such behavior and taking steps to sever ties.” The email thread was intended to be confidential, but copies of some messages were provided to The New York Times. Mr. Kurtzer and the man with the bathrobe story provided their messages directly. In other cases, other people provided the emails to The Times, which secured permission from the authors to quote from them. Today, among Rabbi Rosenblatt’s former squash partners, opinions are deeply divided. Yaacob Dweck, an assistant professor of Jewish history at Princeton University who often played squash with the rabbi as an undergraduate at Columbia, called the discussion on the Wexner email list a smear campaign. “I think this is character assassination of someone who has spent his entire life in the service of the Jewish community, full stop,” he said, describing Rabbi Rosenblatt as “an incredible rabbinic presence in my life” who introduced him to some of his closest friends through the game of squash. He said the rabbi had never invited him to the sauna. But the man who recalled Rabbi Rosenblatt often touching his leg said the rabbi had caused lasting damage. “He destroyed Orthodoxy for so many of us because he just confused everyone,” he said. And the man who said the rabbi ogled him in the shower when he was 12 feels torn. “I think those behaviors he did are definitely inappropriate,” he said. “I would not let my child step into the shower with a grown man.” He added, however: “I have to tell you, he spoke at my mother’s funeral, my grandmother’s funeral — he’s helped me through the years with different difficulties that I’ve had, he’s been nothing but a help to me.” Rabbi Rosenblatt’s contract at the synagogue is up for renewal in a few years. After an unrelated 2012 sex scandal involving Yeshiva University rabbis, some concerned synagogue members offered to buy out the last few years, said a person who was briefed on the offer. The rabbi, that person said, refused to consider it.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.