|

Pope Francis’ Visit to Latin America Will Test His Ability to Keep Catholics in the Fold

By William Neuman

QUITO, Ecuador — Pope Francis has turned heads with bold stands on climate change and income inequality. He helped broker a historic thaw between the United States and Cuba. He has shaken up the stodgy brand of the Roman Catholic Church.

But for all his forays into international diplomacy and deftness at image-making, his trip to South America, which begins Sunday, will test his skills in what could be a much more difficult task: putting parishioners in pews and keeping them there.

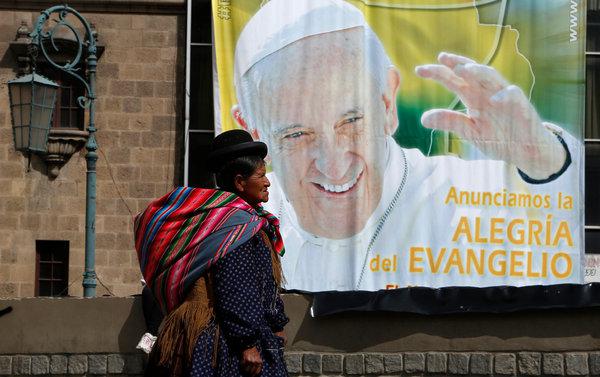

When Francis was named pope in March 2013, becoming the first pontiff from Latin America, he was hailed by many as the kind of figure long needed by the Catholic Church to appeal to its vast base in poorer countries.

His selection signaled how vital the developing world is to the church’s future and offered a way to reverse its erosion in Latin America, a region that holds almost 40 percent of the world’s Catholics but has experienced a steady rise in secularism and competing branches of Christianity.

At the very least, the change of tone — by a pope who champions the poor and eschews many of the luxurious trappings of his office, and even poses for selfies with followers — has raised the hopes of many churchgoers.

“Before Pope Francis, the Catholic Church was out of reach,” said Rosario Zuñiga, a volunteer at a church here who credited Francis with “a new, more human” approach. “He has touched on very sensitive subjects about the attitude of the church regarding its own mistakes, like sex abuse.”

But whether a change of image at the top will be followed by results on the ground remains a pressing question around the region.

In Argentina, Francis’ native country, the director of a Catholic association said that while the pope had personally ignited excitement and interest, attendance at church services and the number of Catholic marriages had barely increased.

“There is an asymmetry,” said the director, Justo Carbajales, 56, a cardiologist. “Argentines have strengthened ties with the figure of the pope, but still not at all with the church.”

Here in the capital of Ecuador, where the pope will begin his visit to Latin America, Archbishop Fausto Trávez acknowledged concern over what he called the church’s decline in recent decades, including a dwindling number of priests.

But he said he thought that the pope’s influence could be seen through increased attendance at Mass, increased collections and a recent rise in the number of seminary students studying to become priests.

“With everything that he says about the poor and about justice,” Archbishop Trávez said of Francis, “the young people become motivated.” He added that many had entered seminary “because the pope is doing things that they would like to do.”

Latin America and the Caribbean have 425 million Catholics, 39 percent of the world’s total, according to the Pew Research Center. But like a multinational corporation facing slumping sales, falling market share, rising competition and a fatigued brand, the church is vulnerable.

As recently as the early 1970s, at least 90 percent of Latin Americans were Catholic. But that number began to fall as Protestant churches grew. In a survey published in November by the Pew Center, 69 percent of adults in Latin America identified as Catholic.

What was once a gradual shift has become a flood, with Catholics now a minority in Uruguay and Honduras, and at just 50 percent in some other countries, according to the survey, which was based on more than 30,000 face-to-face interviews in 18 countries and Puerto Rico. In Brazil, the country with the world’s largest Catholic population, 61 percent of adults now identify as Catholic, the survey found, but 81 percent said they had been raised Catholic.

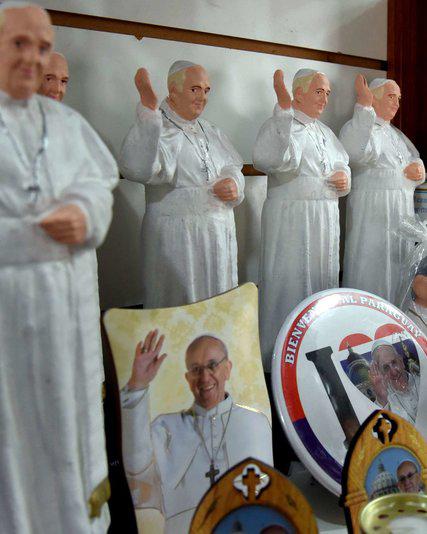

That is the landscape Francis will face on his first trip as pope to Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America, with visits to Ecuador, Bolivia and Paraguay.

“It’s a free market of faith in Latin America,” said Andrew Chesnut, a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University who was a consultant on the Pew survey. “The Catholic monopoly they had for four centuries is over.”

Just months after becoming pope, Francis attended celebrations of the church’s World Youth Day in Brazil. Now, more than two years into his papacy, he returns to the continent of his birth with a message of a church in transformation, having established himself globally as a figure able to provoke both fascination and controversy.

The Vatican said the pope appeared to have delivered a boost to the church, but also said it had no way to measure.

“We have recently observed widespread enthusiasm for the pope and an interest for the church that has been awakened in many countries in the world, including Latin America,” said the Rev. Federico Lombardi, the Vatican’s spokesman. “But we don’t have statistics or more precise data on this.”

Here in Latin America, the pope’s influence has extended beyond the religious sphere.

He played a role last year in secret negotiations between the United States and Cuba to restore full diplomatic relations after more than 50 years of hostility, writing letters to encourage the deal and then arranging for a Vatican meeting between the two sides. President Raúl Castro of Cuba met with Francis in May and even declared that he might consider returning to the church.

In Venezuela last year, President Nicolás Maduro, a leftist whose predecessor, Hugo Chávez, had testy relations with the church, has praised Francis, noting his advocacy for the poor. The shift allowed the Vatican’s ambassador to foster dialogue between the government and the opposition last year.

In Colombia, officials have talked about their hopes for a visit from Francis next year, as possible help in efforts to end more than 50 years of guerrilla war.

In Argentina, where Francis, as archbishop of Buenos Aires, had strained relations with President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, he has mended fences and is often seen as a stabilizing influence for the country.

And in a particularly notable moment for the region, Francis this year cleared the way for the beatification of Archbishop Óscar Romero of El Salvador, a defender of the poor who was assassinated in 1980 and is already regarded as a saint by many.

Nonetheless, the church faces numerous challenges. Many Catholics have left the church for Protestant congregations, especially Pentecostal churches.

Increasing numbers of people who were raised Catholic say that they are no longer associated with any church, especially in countries like Uruguay, Chile and Argentina.

The church has also been hurt by revelations of sexual abuse of children by priests. Francis has spoken out strongly on the topic, and he recently approved the creation of a tribunal to judge bishops accused of covering up or ignoring cases of sexual abuse. But in Chile, he has been fiercely criticized for naming as bishop a priest who was closely associated with a cleric at the center of a notorious sexual abuse scandal.

Although the countries that Francis will visit share in these regional trends, they have generally seen a more limited shift away from the Catholic Church, according to the Pew survey.

Paraguay registered the highest percentage of adults who identified as Catholics, at 89 percent. And both Paraguay and Ecuador have a relatively high percentage of Catholics who say that they practice a “charismatic” form of Catholicism — which sometimes includes jumping up and raising hands during services, or speaking in tongues — a phenomenon that has developed in recent years in response to the rise of Pentecostalism.

The three countries are also among the poorest and smallest in South America, making the pope’s visit in keeping with his focus on helping the poor and ministering to those on the periphery. And all three, particularly Bolivia, have large indigenous populations, which the church is losing.

“If there’s any one sector of Latin American society who have most abandoned the Catholic Church, it’s been the indigenous population,” Professor Chesnut said.

He said Pentecostal churches had been quick to employ indigenous ministers in countries like Guatemala and Bolivia, “whereas you could count, in many of these countries, the number of indigenous Catholic priests on two hands.”

The pope will preside over several Masses expected to draw hundreds of thousands of worshipers, and some will include texts in indigenous languages.

Still, the gap is hard to close. Archbishop Trávez said that although some seminary students in his archdiocese came from indigenous families, none of them speak their native languages.

As for the visit by Francis, Archbishop Trávez said, “I think that there are lots of people who realize that the pope is coming to rescue the lost sheep.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.