|

FRANCIS VISITS THE CHURCH THAT JOHN PAUL BROKE

By Patricia Miller

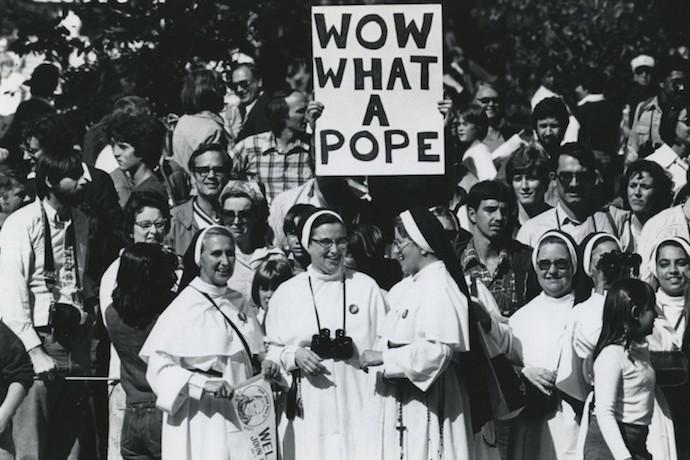

Nearly two and one-half times as many current Catholics think Francis is “more liberal” than they are on “the environment, immigration and distribution of wealth” than those who think he is more liberal on “birth control, abortion and divorce.” – From a New York Times/CBS News poll, release on September 20, 2015 The last time there was this much excitement about a pope’s inaugural visit to the United States, Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall” topped the Billboard charts, Jimmy Carter was in the White House, and cell phones were the size of a brick. But those aren’t the only differences between Pope John Paul II’s historic 1979 visit and Pope Francis’ virgin trip to the US this week. Pope Francis will find a church that is markedly different in a number of significant ways; so different, in fact, that it calls into question whether we can still refer to the Catholic Church in the US. When JPII made his first visit US, he found a church that was in transition but largely intact. Some 40 percent of Catholics went to mass in any given week and there were nearly 60,000 Catholic priests and 135,000 nuns, with the nation’s 18,800 parishes boasting an average of two priests each. The sacraments were still a major part of most Catholics’ lives: there were nearly 1 million baptisms and 350,000 Catholic marriages. The controversy over Humanae Vitae ten years earlier had largely subsided; most Catholics used birth control and most priests ignored the issue. The Catholic Church had tried valiantly over the previous decade to make abortion a major political issue for Catholics as it pressed the issue of a constitutional ban, but with little success. Even the head of the church’s own National Committee for a Human Life Amendment admitted that the “overwhelming majority” of Catholics were apathetic about the issue. Orthodox Catholics fretted about the rise of “cafeteria” Catholics who picked and chose from doctrine, particularly around issues related to sex, but most continued to identify as Catholics, raise their children as Catholics and take part in the life of the church. Some formed reform groups like Call to Action and the Women’s Ordination Conference to agitate for a more democratic church and clerical roles for women. Pope Francis will find a very different church. According to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, only one-quarter of Catholics attend mass every week (CARA has some of the best, most rigorous tracking of mass attendance; other surveys find higher percentages using more generous methodologies.) The number of priests and nuns has declined precipitously; from 58,000 to 38,000 for priests and from 125,000 to 50,000 for nuns. Despite a significantly larger population, there are 1,300 fewer parishes, with an average of just one priest per parish; some 3,500 parishes have no resident priest. The sacraments are no longer as central to the lives of Catholics. The number of baptisms has declined from nearly 1 million to just over 700,000, and the number of marriages within the church has declined by nearly half. Only the number of Catholic funerals has held steady. And while the number of Catholics overall has remained level, that’s largely due to Hispanic migration to the US; some 40 percent of those born Catholic have left the church. But numbers don’t tell the whole story. The church Francis will encounter is fundamentally different in character from the church of John Paul in two important ways. One is the unprecedented ideological polarization of the church. There are today two distinct Catholic populations: one progressive-leaning population that supports the church’s social justice mission and the pope’s call for environmental stewardship, but largely ignores the church’s teaching on sex and family issue; and a conservative-leaning population that’s on board with the church’s anti-abortion message (though not as much with it’s opposition to same-sex marriage) but largely ignores social justice teaching and eschews concern about the environment, having signed on to the free-market, libertarian policies of the Republican Party. As Robert Jones, CEO of the Public Religion Research Institute recently told Sister Maureen Fiedler on NPR’s “Interfaith Voices”: [An] anthropologist might conclude that there are two Catholic Churches on the ground: there’s one catholic church that is concentrated in the Northeast, tends to be white, tends to be older, tends to support Republican candidates, and there’s another one that has a center of gravity more in the Southwest—we now have five states that have majority Latino Catholics in those states—and that tends to be younger, and leans heavily toward Democratic presidential candidates. Will the Roman Catholic Church ever become two churches in reality? Already there are threats of a schism if progressives in the Vatican have their way and allow divorced Catholics to receive communion. As Marquette University theologian Dan Maguire recently wrote in the New York Times:

It’s with this conservative Catholic community that Francis faces the biggest problem. Only 28 percent of Republican Catholics have a very favorable opinion of Francis, versus 53 percent of Democratic Catholics and 45 percent of independents, according to a poll from Faith in Public Life. And while 92 percent of Catholic Democrats think Pope Francis is leading the church in the right direction, only 70 percent of Republican Catholics are confident of his leadership. Just as they do with President Obama, many conservatives question Francis’ legitimacy, like my conservative Catholic brother-in-law who recently told me: “He’s not my pope.” While many Catholics rejected the church’s teaching on birth control because it didn’t align with either their own sense of morality or the realities of their lives, Republican-leaning Catholics have been politically conditioned to ignore Francis’ message on everything from climate change to economics. Francis faces another feature of modern Catholicism that’s vastly different from what John Paul encountered: the unprecedented number of Catholics, mostly progressives, who have given up any hope of reform and have left the church altogether. The number of former, non-practicing Catholics in the US now rivals the number of actual Catholics, comprising a shadow church of lost adherents that will trail Francis as he moves through former Catholic strongholds like New York and Philadelphia that have closed churches by the dozen. And the numbers make it clear that the Catholic rate of disaffiliation isn’t an artifact of the general trend toward non-affiliation; in fact, it’s the other way around: the unprecedented number of Catholics leaving the church is a major driver of the increase in “nones.” A recent Pew Poll, which provides one of the most detailed looks to date at this phenomenon, found that while 20 percent of US adults currently identify as Catholic, nine percent identify as ex-Catholic, with an additional six percent who were raised Catholic (or who had a Catholic parent) identifying as non-practicing “cultural Catholics.” The difference between ex-Catholics and cultural Catholics seems to be how definitively they’ve separated themselves from the church: some 90 percent of ex-Catholics say they will not return, versus just over half of cultural Catholics. Cultural Catholics are also more likely to occasionally attend mass. Not surprisingly, former Catholics tend to be doctrinally alienated from the church, backing major changes, such as allowing women to become priests or sanctioning the use of birth control, at higher percentages than practicing Catholics. A new survey from PPRI, however, makes clear just how politically alienated they are from the church’s US leadership. While former Catholics have a relatively favorable view of Pope Francis, with nearly 60 percent saying he understands their needs and priorities, just 35 percent feel that way about the US bishops—which is 25 points less than practicing Catholics. It’s clear that the decades-long campaign by the US bishops to make abortion the number one issue for Catholics, and their concurrent alignment with the Republican Party on other conservative social and fiscal issues, has alienated a large percentage of Catholics from the church—and they don’t seem inclined to return, no matter how popular the pope is. Another recent study found that sex abuse scandals played a major role in driving Catholics from the church, finding “a significant decline in religious participation” in areas affected by the scandals. (Perhaps the politics of religious affiliation, like “all politics,” is local.) As a result, what we now call the Catholic Church looks very different from the church of 1979. Francis will find a fractured church where a significant number of practicing Catholics aren’t receptive to his papacy and its message, and where a large population of those who would presumably be supportive of his papacy and its priorities are politically and doctrinally alienated. Ironically, this diminished, splintered church—or, nascent churches—is largely the creation of John Paul, the last pope to get a rock star reception when he came to America.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.