|

Doing the Right Thing

By Anthony Lane

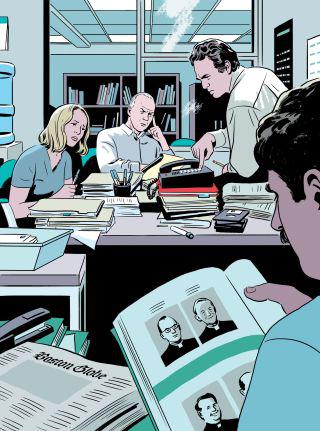

The title of the new Tom McCarthy film, “Spotlight,” refers to the investigative section of the Boston Globe. The main action begins in 2001, with the arrival of a new editor, Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber), lately of the Miami Herald. He has lunch with the head of Spotlight, Walter Robinson (Michael Keaton), who tells him, “We’re trolling around for our next story,” adding that a year or more can be spent on a single case. Recently, the paper ran a column about a local priest who was charged with abusing children; Baron wonders if this was an isolated incident, or if there might be more to dig up. The movie, to put it mildly, has news for us: there’s more. Robinson has a crew of three at his behest: Matty Carroll (Brian d’Arcy James), a quiet family man with a mournful mustache; Mike Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo), pushy and restive, the kind of guy who will never stroll across a street when he can hustle and barge; and Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams). Any film that can make McAdams look resolutely unglamorous is flashing its heavyweight credentials, and “Spotlight” gets bonus points for giving her a thrilling scene in which she struggles to load a dishwasher. The movie adheres to the downbeat and the dun, with cheerful colors banished from our sight. The exception is a youthful choir, chanting “Silent Night” in a church ablaze with the trappings of Christmas. Even then, we see Rezendes watching, with a sour expression on his mug, and clearly thinking, Are these kids safe? He has a point. The film is a saga of expansion, paced with immense care, demonstrating how the reports of child abuse by Catholic clergy slowly broadened and unfurled; by the time the paper’s exposés were first published, in 2002, Spotlight had uncovered about seventy cases in Boston alone. (In a devastating coda, McCarthy fills the screen with a list of other American cities, and of towns around the world, where similar misdeeds have been revealed.) The telling of the tale is doubly old-fashioned. First, there are shots of presses rolling and spiffy green trucks carrying bales of the Globe onto the streets; we could be in a cinema in 1945. Second, the events take place in an era when the Internet still seems an accessory rather than a primary tool. As the journalists comb through Massachusetts Church directories, looking for disgraced men of God who were put on sick leave or discreetly transferred to another parish, we get closeups of rulers moving down lines of text. Don’t expect “Spotlight” to play at an imax theatre anytime soon. On balance, this arrant unhipness is a good thing. So crammed are the details of the inquiry, and so delicately must the topic of abuse be handled, that a more intrepid visual manner might have thrown the movie off track, and one of its major virtues is what’s not there: no creepy flashbacks of prowling priests, or—as in the prelude to Clint Eastwood’s “Mystic River”—of children in the vortex of peril. Everything happens in the here and now, not least the recitation of the there and then. You sense the tide of the past rushing in most fiercely during some of the plainest scenes, as Globe staffers listen to victims like Joe (Michael Cyril Creighton) and Patrick (Jimmy LeBlanc) explain what they underwent decades before. They are grown men, but they are drowning souls. Boldest of all is the brief appearance of Richard O’Rourke as Ronald Paquin, a retired priest, who answers the door to Pfeiffer and answers her questions with the kindliest of smiles. “Sure, I fooled around, but I never felt gratified myself,” he says, as if arguing the finer points of doctrine. “Spotlight” comes across as the year’s least relaxing film, thanks to the attention that McCarthy and his fellow-screenwriter, Josh Singer, oblige you to pay. Consider one conversation between Rezendes and a lawyer named Mitchell Garabedian (Stanley Tucci), about addenda to court documents. It’s so complex that you feel like pausing the action for a quick rewind, yet it has the crunch of truth, all the more so because Garabedian is sitting on a bench and eating from a plastic container while he talks. He’s been wading through the issue of pedophile priests, and of the secret legal settlements made by the Church in response, for many years, and Tucci—whose presence in any film, however grim its theme, is guaranteed to lift the heart—does a great job of showing how an obsession, especially a morally compelling one, can stifle a life. (“I never got married,” he says. “I’m too busy.”) What matters most about Garabedian, though, is that he’s not paranoid, and the movie is uninfected by the noirish unease that drifted through “All the President’s Men.” Even the unseen caller who phones the Spotlight office, or the guy who arrives with a box of hoarded evidence, half-resigned to being dismissed as a crank, turns out to be right, and, as for the knock on the door that Rezendes hears one night, in the throes of the investigation, don’t expect a hooded figure standing on the threshold with a scythe. It’s only Ben Bradlee, Jr. (John Slattery), the deputy managing editor of the Globe, bearing a pizza. If “Spotlight” feels dogged in its procedure, then why does it exert such command? Because, I think, McCarthy is tackling something more basic than paranoia—namely, pride of place, and the way in which it offers both an embrace and a choke hold. “Born and raised,” Robinson says, when asked if he’s from Boston, and the same rings true, throughout the film, for the hunter and the hunted: for the Spotlight squad, for the fund-raisers at a charity gala, and for the authorities at Robinson’s old high school (across the street from the Globe), who harbored an abusive cleric in their midst. And what of the paper’s subscribers, who are fifty-three per cent Catholic? Will they be willing to read of rot in the foundations? Paul Guilfoyle has a wonderful turn as a Bostonian grandee, confident that any unpleasantness can be smoothed away with a hand on the shoulder and a quiet drink. He’s not a monster, or a hypocrite; he’s a decent sort, oiling the wheels of society. To stop them turning, in the interests of justice, takes not only guts but imagination, and that is why Marty Baron, of all people—shy, taut, and humorless, in Schreiber’s clever portrayal—struck me as the hero of the hour. He is mocked for being, as one insider labels him, “an unmarried man of the Jewish faith who hates baseball,” but it is precisely his status as an outsider that allows him to initiate the quest. Folks in the Church, and elsewhere in the city, know what went on, yet they don’t really want to know. It’s all too close to home. Baron wants to know. For a different stroll down the path of righteousness, try “Trumbo.” Jay Roach’s movie follows the tribulations—and exhausted triumphs—of Dalton Trumbo, one of the deftest of American screenwriters. Even if you don’t recognize his name, you will know his work. The script for “Roman Holiday” (1953), for instance, was largely Trumbo’s creation, but he received no onscreen credit, because he had refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee and was confined to the Hollywood blacklist. After all, who’d want to watch a romantic comedy about a princess if it was dreamed up by a goddam Commie? He is played in the film by Bryan Cranston, who nails the natty Trumbo look. Even when he leaves a Kentucky jail, in 1951, having served ten months for contempt of Congress, he emerges in bow tie and hat. More stylish still is his working garb; he likes to write naked, in the bath, with a glass of whiskey, a cigarette in a holder, and reams of paper stacked on a rack across the tub. (This makes him a well-scrubbed match for Waldo Lydecker, the sybaritic wit of “Laura,” from 1944, whose habits were much the same.) Then, there is the ever-rolling stream of his voice. We get the impression, from John McNamara’s script, that Trumbo expressed himself in natural one-liners (“What the imagination can’t conjure, reality delivers with a shrug,” he notes of his prison experience), and you side with his pal Arlen Hird (Louis C.K.) when he pleads with Trumbo, just for once, to shut up. The story is strewn with bit parts. Michael Stuhlbarg is Edward G. Robinson, who sells a van Gogh to meet the legal costs of the accused; Helen Mirren proves beyond reasonable doubt that Hedda Hopper was pure poison; against all odds, Dean O’Gorman makes a convincing Kirk Douglas (an important role, since Douglas helped to break the blacklist by hiring Trumbo to write “Spartacus”); and John Goodman bullies the movie into life as a producer of schlock, who employs Trumbo—or his pseudonyms—when nobody else will touch him. (The deal is tight: a hundred pages, three days, twelve hundred bucks, cash.) All these characters revolve around Trumbo, but where, exactly, does his story go? He is no more or less principled at the end than he was at the start. The drama is stuck with that ethical rigor, and we are left with a near-heretical irony: thanks to this admiring tribute, our hero gets top billing at last, but was he not more beguiling, somehow, as a legendary figure in the shadows?

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.