|

Grave situation: Deaths at Bessborough don’t add up

By Conall ó Fátharta

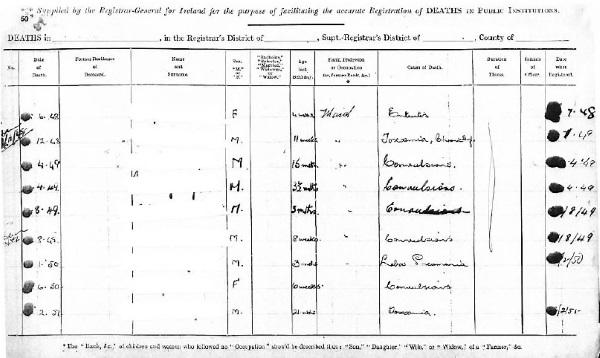

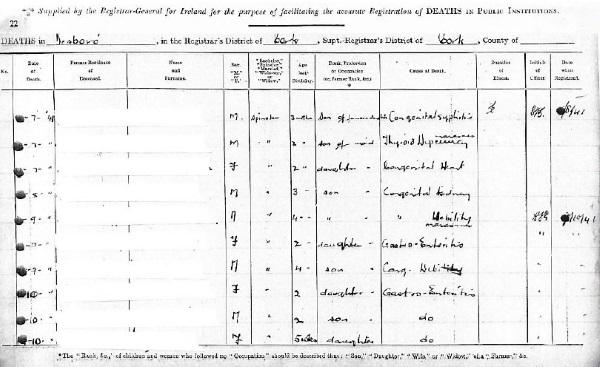

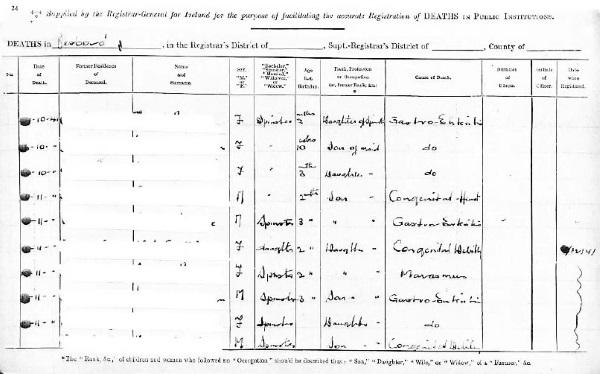

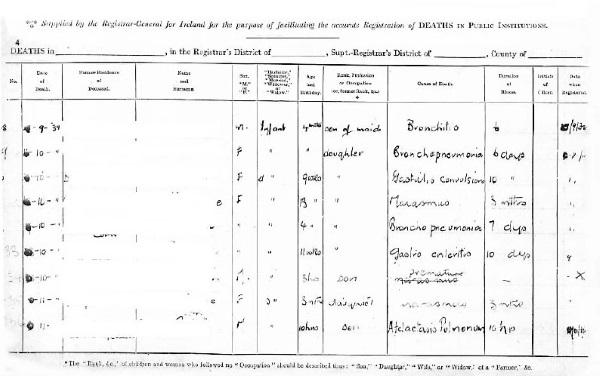

Religious order reported to the State that 353 babies died in Bessborough, but its own register showed 80 fewer deaths. A report found a system of ‘human trafficking’ in which ‘women and babies were considered little more than a commodity for trade’. Conall Ó Fatharta reports THE revelation that the order which operated the Bessborough Mother and Baby home was reporting higher numbers of infant deaths to the State than it recorded in its own death register raises some serious questions. So far, the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary have declined to offer any answers. The order says it will only deal with the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes. It can only be hoped that Judge Yvonne Murphy can get some answers. It is imperative she does. One question is straightforward: Why was the order informing the State of higher numbers of infant deaths in Bessborough than it was recording in it’s own death register? The figures are worth repeating. An inspection report from Department of Local Government and Public Health (DLGPH) by inspector Alice Litster in late 1944 revealed that between March 31, 1938, and December 5, 1944, a total of 353 infants died in Bessborough (out of 610 births). Ms Litster stated that the figures for 1939 to 1941 “were furnished by the superioress”, while those for 1943 and 1944 had been “checked and verified and their accuracy can be vouched for”. However, the order’s own death register — supplied by the Registrar General for Ireland “for the purpose of facilitating the accurate registration of deaths” in Bessborough — for the exact same time period, records just 273 deaths. That is a discrepancy of 80 deaths. Take the figures for 1939 to 1941: For the year ended March 31, 1939, the DLGPH inspector was told 38 infants died. This is also what is reported in the death register. However, for the following two years, the order informed Litster of higher numbers of deaths. For example, for 1940, Ms Litster was told 17 children died. The register records only eight. Similarly, for 1941, the DLGPH was told 38 children died, whereas the register records just 22. For every other year cited by Ms Litster, the figures given to the DLGPH are significantly higher than what is recorded in the order’s own death register. This is particularly the case for year ending March 31, 1943, and 1944. In these years, Litster reports that 70 and 102 infants died, respectively. In the latter figure, this amounted to a death rate of 82% in that year. However, again, these figures differ greatly to the order’s death register, which records 55 and 76 infant deaths in these years. For 1944, this brings the death rate from 82% down to 62%. This 82% death rate had caused such concern at Government levels that it was in regular contact with the head of Bessborough on the issue. So, why was the order content for a DLGPH report to publish higher numbers of deaths than it was recording itself? Perhaps there is another death register for the same period where the order logged the other deaths. However, the order is on the record that the register is the only one in existence. It confirmed this to Tusla via its solicitors in January of this year, when it stated that “all records” it held were transferred to the HSE in 2011 and that it “does not hold any other death register”. Given that Bessborough took in both public and private patients, perhaps the death register only recorded public patients. This appears unlikely, for a number of reasons. Firstly, the figure of 38 infant deaths for 1939 provided to Ms Litster by the order matches the figure in the death register. It would therefore seem that the register was the source for the figures she received from the superioress. However, they do not match for any other year. Secondly, Litster points out that the 102 deaths recorded in 1944 include 35 deaths of children from private patients. The death register records 76 deaths in this period. Adding the 35 private deaths to this figure comes to 111. In short, it doesn’t explain the discrepancy in any way. The Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary is the only body that can provide an answer to all of this. It declined to answer a series of queries posed by this newspaper, stating it was dealing directly with the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes on all such and related matters. It has stated in the past that it reported all deaths to the appropriate authorities at the time. The question then is what is the correct number of deaths for this period? Where are the other 80 children listed as having died at Bessborough in the DLGPH report? Why were their deaths not recorded in the order’s death register? These are questions which must be answered, whether by the order or by the commission. THE story of Ireland’s mother and baby homes is one that has taken decades to reveal. It is still not fully clear. The media has outlined the experiences of women who remain scarred by their experiences in these institutions and haunted by the fate of the children they lost, either through adoption or death. Yet, despite all of these events happening decades ago, a shroud of secrecy continues to hang over the entire period. Firstly, we heard from the women, then we heard about deaths, then we had Tuam. Now, we have the spectre that the number of infant deaths reported to the State at one of the country’s largest mother and baby homes are significantly higher than what the order recorded in its own records. It is worth noting that this latest revelation comes just five months after this newspaper revealed an unpublished internal 2012 HSE report which, based on an examination of the Bessborough records, expressed concerns that death records were falsified in Bessborough, so children could “be brokered in clandestine adoption arrangements”. Prepared as part of the HSE’s examination of the State health authorities’ interaction with the Magdalene Laundries for the McAleese Committee, it highlighted the “wholly epidemic” infant death rates at the home as revealed in the death register and added: “The question whether indeed all of these children actually died while in Bessboro or whether they were brokered into clandestine adoption arrangements, both foreign and domestic, has dire implications for the Church and State and not least for the children and families themselves.” Those words take on a whole new significance in light of the discrepancy in the number of deaths recorded by the order compared to the State. Rumours of such a system have abounded in Ireland for years. Mothers have spoken of being told their child had died, but having never seen the body. The HSE report into Bessborough describes the number of recorded deaths as “wholly epidemic”, “shocking” and a “cause for serious consternation”. Despite this, it went ignored. When it was revealed by the Irish Examiner earlier this summer, the reaction of the Government was to deny any knowledge of it, then admit that two departments — the Department of Health and the Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA) — had seen it, before dismissing its contents as “conjecture”. New material released under FOI reveals that not only was the report seen by two departments, its contents compelled Dr Declan McKeown — consultant public health physician and medical epidemiologist — of the Medical Intelligence Unit in the HSE to write to principal officer at the DCYA and member of the McAleese Committee Denis O’Sullivan on November 1, 2012, to warn that “adoption, birth and registration and the recording of infant mortality” were issues that may require “deeper investigation”. Clearly, senior medical professionals within the HSE were telling DCYA officials that the issue of how deaths were recorded needed to be investigated, not to mention how adoptions were contracted and how births were registered. Yet, it took almost another two years and worldwide headlines about a mass grave in Tuam before the Government felt compelled to act and order a State inquiry. If any action had been taken on the contents of the HSE report or on the words of Dr McKeown, the discrepancy in the number of deaths contained in the register versus what was reported to the State could have been found years ago. Apart from uncovering a death rate higher than that found in Tuam two years later, the Bessborough report outlined a system of “institutionalisation and human trafficking”, in which “women and babies were considered little more than a commodity for trade amongst religious orders”, in an institution where women were provided with little more than the care and provision given to someone convicted of a crime against the State. It revealed evidence from an admission book from 1929-1940 that adoptive parents were charged a sum ranging from £50 to £60, payable on a monthly scheme in exchange for their child, before advising that “further investigation into these practices is warranted”. While no specific criteria for assessing adoptive parents could be found, minutes from meetings of the Sacred Heart Adoption Society’s board of management suggested prospective adoptive parents were assessed “on the basis of their earnings, the size and condition of their home, and their social status within the community (not to mention the fundamental expectation that couples were practising Catholics)”. However, despite all of this, the HSE report on Bessborough was not included in the final HSE submission to the McAleese Committee. While included in various earlier drafts, Denis O’Sullivan emailed Gordon Jeyes on November 7, 2012, to advise that any issues around mother and baby homes were outside the remit of the McAleese Committee. “Material included beyond that is beyond the scope of our work — eg, the scope does not extend to an examination of other places of refuge eg mother and baby homes, other than in the context of referrals from Magdalene laundries. “If there are separate and validated findings of concern emerging from such additional research, obviously they should be communicated by HSE and through a separate process.” The previous month, Nuala Ní Mhuircheartaigh of the McAleese Committee had emailed then HSE Assistant National Director of Child and Family Services Phil Garland acknowledging the Bessborough report, but stating it was “heavily focused on broad narrative and context rather than fact.” However, it wasn’t just Bessborough that was on the radar at this point. Serious concerns were also being reported about Tuam Mother and Baby Home — again almost two years before it made headlines around the world. In June, the Irish Examiner revealed that senior HSE officials expressed concern that up to 1,000 children may have been “trafficked” to the US from the Tuam Home in “a scandal that dwarfs other, more recent issues with the Church and State”. The revelations were contained in an internal note of a teleconference in October 2012 with Phil Garland and then head of the Medical Intelligence Unit, Davida De La Harpe. THE note relays the concerns raised by the principal social worker for adoption in HSE West, who had found “a large archive of photographs, documentation and correspondence relating to children sent for adoption to the USA” and “documentation in relation to discharges and admissions to psychiatric institutions in the Western area”. It notes there were letters from the Tuam Mother and Baby Home to parents asking for money for the upkeep of their children and says that the duration of stay for children may have been prolonged by the order for financial reasons. It also uncovered letters to parents asking for money for the upkeep of some children that had already been discharged or had died. The social worker had compiled a list of “up to 1,000 names”, but said it was “not clear yet whether all of these relate to the ongoing examination of the Magdalene system, or whether they relate to the adoption of children by parents, possibly in the USA”. At that point, the social worker was assembling a filing system “to enable her to link names to letters and to payments”. “This may prove to be a scandal that dwarfs other, more recent issues with the Church and State, because of the very emotive sensitivities around adoption of babies, with or without the will of the mother. “A concern is that, if there is evidence of trafficking babies, that it must have been facilitated by doctors, social workers etc, and a number of these health professionals may still be working in the system.” The note ends with a recommendation that, due to the gravity of what was being found in relation to Tuam, an “early warning” letter be written for the attention of the national director of the HSE’s Quality and Patient Safety Division, Philip Crowley, suggesting “that this goes all the way up to the minister”. “It is more important to send this up to the minister as soon as possible: with a view to an inter-departmental committee and a fully fledged, fully resourced forensic investigation and State inquiry,” concludes the note. It’s unclear what, if any action, was taken on foot of this dire warning from the HSE. What is clear is that since 2012, the Government has been advised of serious concerns with both Bessborough and Tuam Mother and Baby Homes. It was specifically told that the number of deaths recorded were “a cause for serious consternation” and that the issue of how these deaths were recorded needed to be investigated. It was advised that what was being found in relation to Tuam warranted a full State inquiry. Now, we know that there are large discrepancies in the deaths reported to the State versus those recorded by a religious order. We now have a State inquiry. Let’s hope it can get to the bottom of why the figures don’t add up.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.