Untold Story of How the "Spotlight" Team Turned a Journalism Procedural into an Oscar Front-runner – Awardsline

By Mike Fleming

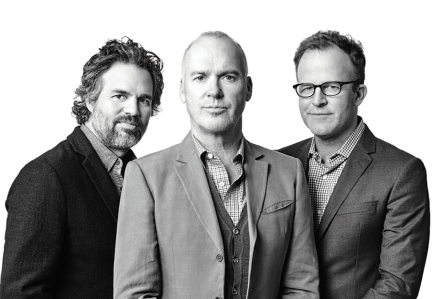

Spotlight has been in the Oscar hunt since Toronto Film Festival audiences gave it a long, thunderous standing ovation. At the heart of the film is a team of dogged journalists whose expose of the shameful Boston Archdiocese cover-up of pedophile priests led to the forced resignation of the all-powerful Cardinal Bernard Law. The film subsequently has been as well-reviewed as any this fall, even getting a thumbs up from the Boston Archdiocese, which acknowledged the role the Boston Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Spotlight team played in forcing the church to confront a malignancy and renew its vow to stop predatory priests, who previously were moved to other parishes, leaving shattered lives and hush-money payouts in their wakes. Despite its incendiary subject matter, Spotlight so far hasn’t had to bear the brunt of accuracy attacks that hobbled so many fact-based Best Picture aspirants in recent years. Director Tom McCarthy and his co-writer Josh Singer took a page from The Globe’s investigative Spotlight team playbook: They stuck to the facts. For The Globe, that mandate grew out of a series of 1992 stories the paper wrote about predator priest James Porter, which caused Cardinal Law to threaten to bring down the wrath of God to ostracize the newspaper in the Catholic community comprising the majority of its readership. The topic of predatory Catholic priests was just as polarizing for Hollywood, a factor in DreamWorks dropping the picture before Open Road signed on. Other inherent risks in the film were structural: no traditional lead, and, as Spotlight reporter Mike Rezendes says, “no Hollywood cliches, no car chases, no sex scenes and no guns. Just a true story.” The filmmakers contented themselves with an honest exploration of a journalist’s work, perfectly encapsulated by ex-Spotlight editor Walter “Robby” Robinson during the film’s Boston premiere: “We as reporters stumble around in the dark, one step forward and two steps back, and through all the tedium you keep going. Maybe you get some dumb luck, but in the end you get that story and it was all worthwhile.” You might think you’ve heard the whole story about the journalists and the actors who played them—Robinson (Michael Keaton), Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo), Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams), Ben Bradlee Jr. (John Slattery), Matt Carroll (Brian d’Arcy James) and editor Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber)—but here are a few threads that informed how the unlikeliest Best Picture contender came to be. Some Actors Don’t Believe the Perfect Script Is One that Has Them in Every Scene

Of the six actors who star in Spotlight, Ruffalo, Keaton, McAdams and Schreiber have carried movies, and yet it wasn’t difficult for them, or for Stanley Tucci or Billy Crudup, to commit to a movie with no traditional lead to anchor as with most movies. Ruffalo so loved the script that he committed overnight; Keaton signed on almost as quickly. So what happened to the notion of actors being protective of the big moments that matter in awards season? Ruffalo, for one, says he only began having fun as an actor when he stopped prioritizing his needs over the picture. “I’d given up long ago the idea about the awards or, ‘Am I going to have my acting moment?’ ” he says. “I found that chasing awards and outcomes and trying to impress people, and all the things that happen when you get really protective about your moments, left me feeling empty. Before The Kids Are All Right, I wasn’t enjoying it anymore. I went into Kids thinking that was going to be my last movie. And then I had so much fun. It was an ensemble and it was all that I wanted from acting. Here, a lot of that came from Tom. The agreement we made, without even speaking about it, was that we’d share and respect each other and play like a team. So when the moment comes where someone says, ‘Do you think you should be up for lead?’ I’m like, ‘No, man, I’m in an ensemble. My part isn’t the lead.’ I know Michael felt the same and it happened naturally, out of the spirit of the filmmaking.” The results are clear in the subtle moments each actor has. Singer says he and McCarthy embraced that ensemble structure at the start, then wrote hundreds of drafts to hone a gentle chemical balance. “Tom made a bold decision to keep six characters alive, with individual arcs and moments, and he’s just so good at small moments so you don’t write over the top,” he says. “Mike and Sacha’s characters were always prominent, and we’d do a draft where we would focus on Robby and make sure we got that arc right. Then, we had Marty Baron, this moral and ethical national treasure who holds the powerful accountable. Did we give him enough? And then you want to lure guys like John Slattery and Brian d’Arcy James, and their characters need enough meat on that bone. We did rewrites up until production, and it became a question of whether we could get the financing for this, because we felt we had something really special.” Ruffalo says freedom from self-protective urges opened the door to more enjoyable things. “When we were sitting in those rooms, those ensemble scenes were just magic,” he says. “You are just sort of floating in it and it’s shared. No ego, just serving the story. That becomes fun and easy. Tom led us that way starting in rehearsals, and you find yourself marveling at watching your team play: ‘Oh my god, that was a great moment for Michael. Rachel, man, the way she listens. Look at Brian and how he mastered Matt Carroll’s accent in that scene.’ It became more enjoyable as it went along.”

It stoked embers of an activist instinct Keaton had as a young man. “It’s a blessing to be in something that will change lives,” he says. “How many people get to have my job, where you get to be in something that’s good, that will affect change in a positive way? I went to college in the ’70s. I went to anti-war demonstrations. We were aware of the civil rights movements. To think that someday you’d be doing what you love, and it could have an effect on society, that’s pretty great. In this movie, it’s stuff that people have been talking about a long time. But then when you see it this way, you realize that it’s shocking this hasn’t been addressed before on film. In that regard, it kind of feels bold.” How Early Game of Thrones And Julian Assange Setbacks Helped Forge Spotlight Robinson’s comment about stumbling around in the dark isn’t a phenomenon singular to journalists. Adversity for the filmmakers helped shape Spotlight as well. People in Hollywood who know will tell you that McCarthy is the reason Peter Dinklage plays Emmy-winning Tyrion Lannister in Game of Thrones. When he first transitioned from actor to filmmaker, McCarthy directed Dinklage’s breakout turn in The Station Agent, and then was the original director of the pilot of the hit HBO series. That didn’t turn out well—credit for the episode went to another filmmaker—and it perhaps focused McCarthy toward a wheelhouse that involves intimate character dramatic structures with which he finds a personal connection. In Spotlight, that connection was being a Catholic sometimes conflicted by an institution run by imperfect men.

McCarthy and Singer’s path on Spotlight began at DreamWorks, which let the film go after the Singer-scripted Julian Assange-WikiLeaks drama, The Fifth Estate, failed at the box office. While Assange’s early fame led to a small stampede of development projects, his coldness and personal problems overshadowed a promising subplot of how The Guardian, in tandem with The New York Times and Der Spiegel, coordinated with WikiLeaks to publish groundbreaking, leaked, classified U.S. documents. Those types of secondary characters are front and center in Spotlight. “We had two books, one by The Guardian guys and the other by Daniel Domscheit-Berg,” Singer says. “It felt fresh when we pitched Daniel’s coming-of-age story before he realized Julian was something of a monster. It was like there were two movies and, after I spent time with The Guardian guys, I was torn. That pure journalism process was so interesting to me. You could have written a whole movie about that. But it was my first film, and unfortunately by the time it came out, Assange didn’t feel so fresh. “I just saw The Guardian guys at a BAFTA screening for Spotlight, and I told them that so much of what I learned from them is on the screen.” Who Cares If Reporters Don’t Sleep with Sources or Are Boring?

When the Pulitzer Prize-winning Spotlight team unveiled the film to their Globe colleagues at Coolidge Corner in Boston, they were treated like conquering heroes. Many in the audience laughed at how the actors captured each mannerism, down to Baron’s monotone speech cadence, or when Rezendes sprints up a Globe escalator that, Robinson noted, was usually broken. The reporters seemed relieved the film pleased their colleagues as much as film critics. “The genius of the movie is that it somehow makes exciting the drudgery of investigative reporting,” Rezendes says. “There’s that scene in the movie where we are building that church database (of predator priests). That took three grueling weeks and I don’t think our eyesight ever really recovered. It was incredibly tedious, and boring. But there in that movie, with that wonderful score, cutting back and forth between Sacha, Robby, myself and Matt Carroll, it seemed riveting.” It was a different set of sheets that gave Pfeiffer the most consternation. “I had the most concerns of, ‘Is it a good idea to let somebody make a movie about your life and give them license to potentially fictionalize it?’ ” Pfeiffer says. “We got asked very personal and sometimes intrusive-feeling questions in the process. Like, ‘How did this affect your marriage?’ I had this growing sense of concern and even doom. What are the Hollywood versions of our lives going to be like, and are we going to regret this?” Pfeiffer later admitted during a post-screening Q&A that she “was convinced there would be a love affair—we’d be depicted sleeping with our sources—and there would be a sex scene. (The filmmakers) didn’t do that and focused instead on the slow process of developing sources. They did tell me that as a routine part of the process, they (send out) the script for notes and one said, ‘This movie could use a bit of romance. What about an affair between McAdams and Ruffalo?’ So I wasn’t paranoid—it was on the table—but luckily the director and screenwriter felt it would diminish the story. I think we got lucky.” Singer confirmed the suggestion was made, but added: “We were definitely never going to do anything like that. I remember one actor in particular read a version of the script and said, ‘Why doesn’t Mike have a family and why isn’t he a practicing Catholic? Then he can really rage against all this, and wouldn’t that make him more dramatic?’ I thought, ‘It would make him more Hollywood,’ but it’s that way because Mike isn’t a practicing Catholic. We felt a deep responsibility to be faithful to the story, to the reporters, and the survivors.” Spotlight’s Six Degrees Connection to the Truth Saga of Dan Rather and Mary Mapes

If Spotlight has proved to be the most compelling procedural since All the President’s Men, in which good journalism was done right, then the other buzz-worthy journalism film this year, Truth, is its polar opposite. Had either Mapes or Rather read The Globe, chances are they never would have gambled their careers on a hasty expose that relied on ex-Texas National Guard Officer Bill Burkett, who provided documents they couldn’t verify. Robinson and Rezendes wrote stories about George W. Bush’s spotty record in the National Guard during Vietnam, including one in which their attempts to verify charges by Burkett just didn’t pass their sniff test. “Six months before, their source came to us with a different story and we debunked him, and I thought it was a bogus story,” Rezendes recalls. “I don’t know if Rather and Mapes read any of it, but the information was out there. They rushed it. Spotlight was about not rushing it until you get it right, even though there are always time pressures.” Bradlee saw Truth while he was in Toronto for Spotlight. To say he was unimpressed is an understatement: “They got the story wrong, and yet they made a movie out of it?” he says. “I just think the whole thing is inherently flawed, like a make-up to justify a story they never had right.” Recalling The Globe’s early reporting on Father Porter that incurred Cardinal Law’s wrath, Bradlee says, “We wrote hundreds of stories on that guy, but we couldn’t get the internal church documents we were able to get in the Father John Geoghan case. That’s what made the difference. It made our story bulletproof.” The Globe Reporters Haven’t Gone Hollywood

Even though they milled around Hollywood at premieres and awards events, the Spotlight journalists don’t seem overwhelmed by sudden screen glory. Four of the six major characters—Rezendes, Robinson, Pfeiffer and Carroll—still write for The Globe. Bradlee took a leave to write a Ted Williams book that has its own movie potential, and Baron runs The Washington Post. Robinson left to teach for seven years but missed the action and returned, as did Pfeiffer when she became a public radio star but lamented reading Globe-originated stories she once broke. “This whole fame thing was very awkward for us, frankly, but at least it’s a movie about us doing our jobs,” says Rezendes, whose spartan lifestyle in the film drew laughter from his colleagues during the Boston screenings. “I don’t expect our lives to change, but maybe it will bring us some better news tips. “A few things have changed,” he acknowledges on second thought. “Ruffalo’s character lived like a monk. I still live in the same part of town, but I’ve got a nicer apartment now.” To see a video of McCarthy, Singer and producers Steve Golin and Nicole Rocklin discussing Spotlight at Deadline‘s The Contenders event, click play below:

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.