A Priest, a President, a Predator

By Tony Messenger

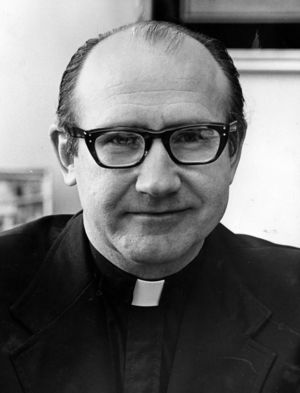

In 1983, Father Daniel O’Connell served as a religious mentor to a young female student from Holy Cross College. The Jesuit priest was a chaplain at Loyola University of Chicago. The student, who in legal filings is known as Jane Doe MB, was studying abroad in Italy, where Loyola had a campus and Father O’Connell was assigned. Over the course of two semesters, O’Connell sexually assaulted Jane Doe MB. For a while, she kept her silence. Two years later, I was a freshman at Loyola, living in a coed off-campus dorm called Gonzaga Hall that had its own resident priest. Father Daniel O’Connell was that priest. He was my religious mentor. So it was with a considerable amount of shock and sadness that I opened an email from the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, or SNAP, last week describing two legal settlements with women who, like me, trusted Father O’Connell, but, unlike me, were horribly violated by him. Jane Doe MB had actually settled with the Jesuits back in 2003, when the religious order found her allegation against Father O’Connell credible and paid her $181,000. Part of that agreement called for keeping the abusive priest away from other women in a ministerial setting, which didn’t happen, leading to a new settlement of $82,000. Jane Doe MB was a St. Louis University student who sued in 2012 over abuse that happened in the late 1960s. Father O’Connell would later become the president of SLU, from 1974 to 1978. Her case settled for $200,000. I can’t help but think that at one point, the women had a relationship with Father Dan that was similar to the one I had. I was considering the priesthood and studying psychology, his area of study and teaching. Often, after he would say Mass at the dorm, I’d knock on his door and enter his Spartan room, sit on the side of the bed or a chair and talk about my interest in becoming a Catholic priest. He was kind, gentle and smart. He guided me away from the priesthood because I was wavering. You have to be sure, he said. You had to know. About 14 years ago, Father O’Connell and I relived those conversations. The Roman Catholic Church’s sex abuse scandal, as broken by the Boston Globe, was a worldwide story continuing to spread like wildfire as more victims came forward. It was March 2002 and I called Loyola and asked Father O’Connell if I could talk to him for a column. His advice was sound, just like it had been all those years ago. He was open about the church’s failures. We talked about his ability to communicate with students, to show he cared, with a simple touch on the shoulder, and how the abuse scandal would change that. “That touch meant something,” he told me, for a column I wrote in the Columbia Daily Tribune. “It was not an inappropriate touch. It meant, ‘Father Dan, my friend, is there for me.’ These things are important. But they must be balanced.” I read those words back now and shudder. I think of my friends in Gonzaga Hall, young women who, like me, treasured Father Dan, and wonder how many of them knocked on that same door, but instead, entered a chamber of horror. Within a year of speaking those words to me, Father O’Connell would resign from Loyola as a result of his assault of Jane Doe MB. But like the various dioceses of the Roman Catholic Church which once moved abusive priests from parish to parish, the Jesuits incomprehensibly left Father O’Connell on the job. Eventually he would teach and minister again, at Fordham and Georgetown, and abroad in Germany. Advocates from SNAP say these breach of contract settlements are an important new chapter in the evolution of the church’s child abuse scandal. Long before the prevalence of abuse cases was known, many of them were settled quietly, just as Jane MB 929’s case had been so many years ago. They are urging the Jesuits to seek out other potential victims of Father O’Connell, and asking victims who signed such agreements with the church or its various arms to speak up if they weren’t kept. For me, I keep going back to one scene in the movie “Spotlight,” which portrays the Globe’s relentless investigation into the scandal, and now I see it in a more nuanced light. In the scene, the archbishop’s spokesman meets in a bar with his old friend Walter “Robbie” Robinson and tries to steer the editor away from the story, reminding his fellow Catholic of all the good that priests do. As long as I’ve read about and written about the scandal surrounding the church of my youth, I’ve never had a problem separating those abusive priests, and the church’s horrendous cover-up, from the priests who helped mold my faith. But I never knew one of the priests accused of abuse. Until now. It changes the calculus of one’s emotional balance in reacting to allegations of abuse. In 2002, I asked Father O’Connell how fellow priests were dealing with the controversy. He grew up in St. Louis (and may be living here again) and knew many of the priests from this area accused of either abuse or cover-up. “We’re all hurting,” he said, adding, “We don’t abandon our sinful brothers and sisters.” In my heart, I’d like to think Father Dan knew he was talking about himself.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.