|

Will Pope Francis confront the ‘devil’ in the Mexican Church?

By Rafa Fernandez

MEXICO CITY—When Pope Francis visits Mexico from Feb. 12-17, many people will be watching to see if he finally addresses the Vatican’s failures to prevent and punish cases of child sexual abuse by some members of the Mexican clergy. There’s plenty of such scandals to address—from a priest in Oaxaca accused of abusing indigenous minors to the fugitive priests of San Luis Potosí on the run from sexual abuse charges. There are other cases of the Church hierarchy allegedly protecting accused pedophile priests such as Nicolas Aguilar Rivera, who was transferred from Puebla to Los Angeles, California, after facing several accusations in Mexico. But perhaps the most notorious case is that of Marcial Maciel, a priest accused of sexually abusing dozens of minors during his tenure as the leader of the powerful Catholic order known as “The Legionaries of Christ.” Maciel founded The Legion in Mexico City in 1941 as a movement to prepare young men for the priesthood and Catholic leaders from across Latin America. Today, the Legion is best known for creating dozens of private schools and universities that primarily serve Mexico’s middle- and upper-classes. In a recent interview with a Mexican reporter, Pope Francis said Maciel, who died in 2008, was “sick, greatly sick.” But he downplayed the Vatican’s involvement in any cover-up. The pope told Televisa that Maciel most likely had an enabler within the Vatican—someone who “suspected and didn’t know” about the priest’s pederasty. But many Mexican victims who were sexually abused by Maciel believe the pedophile priest must have been protected by more than one individual in the Vatican. A cover-up of that magnitude would require the protection of many. “There’s an entire institutional strategy to manage these cases from the inside, in secret and with the intention of disqualifying those who speak out,” charges Alberto Athie, a former priest who now helps sexual abuse survivors.

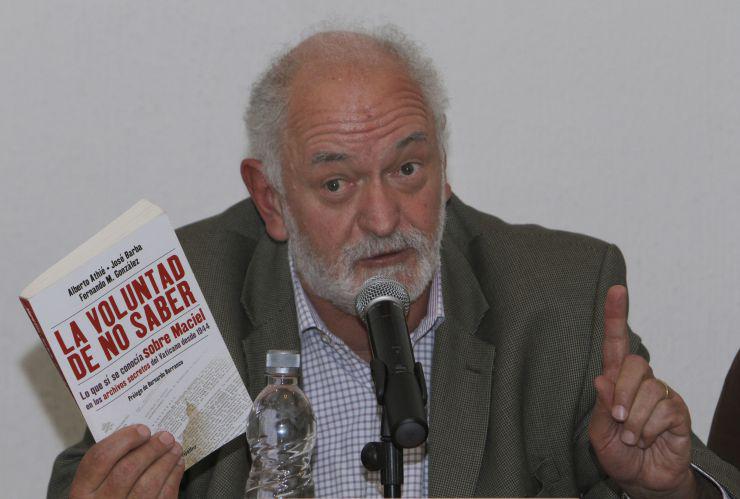

AP Photo/Marco Ugarte

February 5, 2014. Alberto Athie holds up a book he coauthored about Marcial Maciel's abuses. Athie renounced the priesthood in 2003 after meeting a victim of Maciel and seeing how top clergymen in Mexico discredited the allegations as lies and conspiracies. Now that the pope is visiting Mexico, Athie wants the Holy See to publicly and fully acknowledge this and other scandals, which hopefully would be a first step towards some type of reform within the Church. “Clerical pederasty still prevails,” Athie told Fusion. “The [Vatican’s] structure hasn’t been touched.” Many sexual abuse survivors agree that the issue still needs to be dealt with. The memories and pain of what happened have not faded with time. “I came out crying with semen running down my leg. He forced me to. He masturbated me, I had never masturbated, and I came out very confused because I was feeling pain and pleasure at the same time,” Jose Barba, a renowned Mexican academic, told Fusion. Barba was a devoted student of the Legionaries of Christ and on his way to becoming a priest when he says he was first molested by Maciel in 1955. Instead of becoming ordained, he left the Legion in 1962. “He chose students as if they were cattle. He wanted middle class boys, white-skinned, blonde, and attractive.” - Jose BarbaBarba says Maciel told him that masturbating him was an “act of charity” that would ease him from pain in his urinary tract. “He told me he had permission from Pope Pius XII to get his genitals massaged by some nuns,” he said. It would take many years before Barba could speak out about the abuse. “For a long time I thought I was the only one,” he says. “Then other victims started coming out and we organized.” Barba and seven others eventually denounced the abuses before Vatican authorities in the late 1990s. But the process took years and faced fierce resistance within the Holy See. In 2005, facing great outcry over the Church’s sexual abuse scandals in Mexico and around the globe, Pope Benedict asked Maciel to step down from leading the Legionaries. Maciel went into reclusion and died quietly in 2008 without ever facing justice.

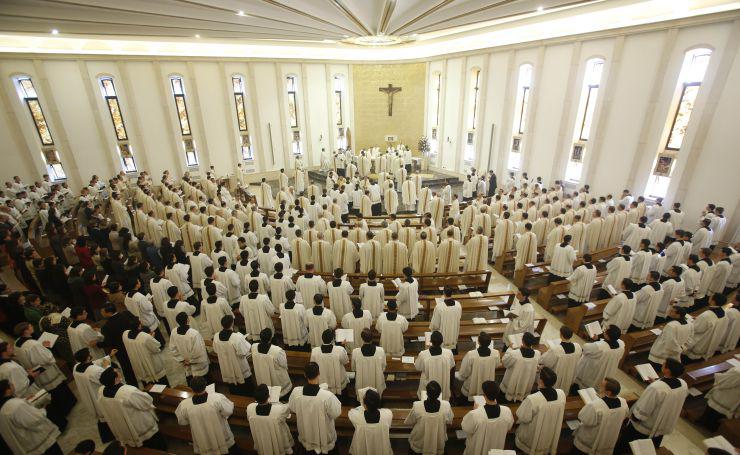

AP/Riccardo De Luca

Feb. 25, 2014. Prelates attend a mass celebrated by Cardinal Velasio De Paolis in the Legion of Christ main headquarters, the Ateneo Pontificio Regina Apostolorum, in Rome. Cardinal De Paolis celebrated his final Mass as papal delegate and was sent off with a round of applause from a congregation eager to take back the autonomy that was wrested away from it by Pope Benedict XVI in 2010. Benedict intervened after a Vatican investigation determined that the Legion had been infected by the influence of its founder, the late Rev. Marcial Maciel. “I think it’s shame, fear, social preoccupation,” says Barba, when asked why it took so long to publicly denounce Maciel’s abuses. This prolonged silence among victims is not uncommon. Studies on sexual abuse have found that many survivors generally speak out once they’re older and have reached some sort of social comfort and security in their lives. “No one talked,” says Barba. “One person took 25 years to tell me the truth.” The victims who have spoken out claim the Legionaries were especially good at discrediting them and framing abuse allegations as ill-conceived attacks against their religious order. Fusion reached out to the Legion for comment but did not receive a response. “Marcial Maciel had the help, the complacency and the complicity of many, which allowed him to lead a life of luxury, riches, lies, simulation and crime, protected by a great mantle of impunity of which no one is in charge nor claims responsibility,” writes Carmen Aristegui, a Mexican journalist who published several interviews with sexual abuse survivors in a book titled Marcial Maciel: History of a Criminal. In her book Aristegui exposed how the Legionaries became important fundraisers for the Vatican, and how a machiavellian and wildly-charming Maciel managed to gain the blind trust of Pope John Paul II, who was widely beloved by Mexicans.

AP/Plinio Lepri

Nov. 30, 2004. Pope John Paul II gives his blessing to Father Marcial Maciel during a special audience at the Vatican. When the scandals eventually became too big to contain, the Vatican dismissed the problem as one caused by a few bad apples. “Like the lone assassin; the lone pederast,” Saul Barrales, one of Maciel’s many victims, told Aristegui. But Maciel didn’t act alone. Investigations found that he built an influential support network through the congregation’s charities, its private universities and its high schools. His charisma, calculated and contagious, fooled many in the country’s well-heeled upperclass who embraced the priest and become unconditional donors to his religious order. Maciel even officiated the wedding ceremony of Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim and was especially close to many prominent businessmen in the northern city of Monterrey. “Maciel’s financial strategy targeted the wives of wealthy men,” writes journalist Jason Berry for the National Catholic Reporter. For a time Maciel was the rockstar of the Mexican Church, a man capable of bringing back religious values to the education system and instilling a culture of charity amongst Mexico’s elites. But that quickly faded once the scandals surfaced. Since Maciel’s death, there have been various news reports that have sparked public outrage about his abuses, his alleged drug addiction, the children he conceived with women, and his shady finances. But Mexicans have yet to closely analyze the support network that Marciel had with the Vatican and Mexican society, which enabled the priest and his Legionaries to operate with total impunity for so long. Now that the pope is visiting Mexico, the world’s second-most Catholic country, it’s a chance for the Vatican to finally confront an old wrong in all its dimensions. But breaking the silence won’t be easy for Francis. To the surprise of many, the pope recently issued a customary indulgence pardoning the Legionaries for their sins. That indulgence didn’t necessarily pardon Maciel, but that’s how some critics are interpreting it. Roberto Blancarte, founder of Mexico’s Center for Religious Studies (CEREM), thinks the pope will avoid talking about Maciel’s pederasty and the Legionaries during his trip. And the Mexican Church can’t be expected to bring it up either, because “it’s a subject they’ve tried to leave in the past,” Blancarte says. Barba thinks Francis may eventually try to promote some type of reform within the Church, but that won’t be an easy fight.

Rafa Fernandez De Castro

Jose Barba has learned to forgive but not forget. “He may have the will to do, but can’t do because the Roman Curia won’t allow him,” says Barba, who thinks Francis will continue to project himself in Mexico as a humble “pope for the poor.” That image has gained Francis public trust and Barba thinks he could use that support to challenge the Roman Curia that’s preventing change. However, Barba also sees Francis as “a pope of gestures” and one who “talks in generalities.” Ultimately, Barba thinks the pope is unlikely to reform Church laws to prevent and punish future sexual predators like Maciel. “I’ve already seen three popes say and do nothing,” he said. There’s rumors Francis might try to meet with sexual abuse survivors in private during his trip to Mexico. Many hope such a meeting would push the pope to go beyond soundbites and apologies. It remains to be seen how far this new pope is willing to go.

Barba painfully remembers what a Vatican lawyer told him when failing to push the canonical complaint he and seven others filed against Marcial Maciel:

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.