Oscar-nominated Movie Spotlight Looks at the Catholic Church’s Shameful Response to Child Sexual Abuse in Boston

By James Mottram

There are many shocking things about Spotlight, Tom McCarthy’s new film about the discovery of widespread sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church, but perhaps the most shocking thing of all comes at the end. Fear not, this is not a spoiler. Before the credits roll on this Boston-set story, a caption lists hundreds of cities around the world where such crimes were subsequently uncovered. It will make you gasp with disbelief. “It’s astounding!” admits Stanley Tucci, one of the stars of Spotlight. “But if you know it’s happening in Boston, you know it’s happening all over the place. If it’s that systemic in one city … the Catholic Church, it’s all connected. It’s all connected!” He breaks off, aware that he’s beginning to sound like his character, eccentric lawyer Mitchell Garabedian. “It’s not like this is a new thing. It’s appalling. It’s disgusting.” Spotlight doesn’t just examine how priests targeted children in their parishes. Set in the early 2000s, it showcases how the four-strong investigative team at The Boston Globe uncovered a widespread cover-up within the Catholic Church, as predatory priests were simply removed from one diocese, sent to a treatment centre and quietly reintegrated into another parish “where the abuse would continue”, as McCarthy puts it. “That is the heartbreaking thing,” adds the director, who co-wrote the screenplay with Josh Singer (The Fifth Estate). “You find out about it and you allow it to happen somewhere else.” Among the acres of research he and Singer did, they met with a few of the Boston victims of this systematic molestation. He says: “There was so much hurt and anger, which was understandable. It’s really difficult to recover a life after that kind of abuse.”

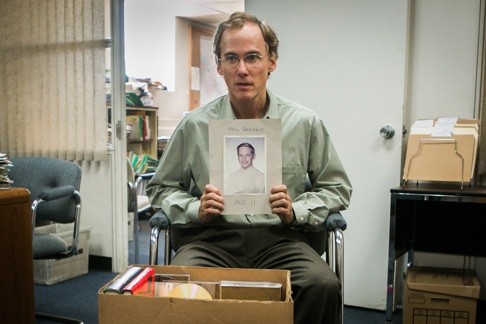

At least Spotlight might bring into focus the horrors these victims endured. The film has been one of the most celebrated of last autumn’s festival circuit, and will go into the Oscars with six nominations – including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Supporting nods for Rachel McAdams and Mark Ruffalo, two of the quartet of actors (alongside Michael Keaton and Brian d’Arcy James) who make up the “Spotlight” team. On the surface, Spotlight is also a love-letter to investigative journalism, recalling other newspaper-set procedurals such as All The President’s Men and Zodiac. Set in an era where the internet was still in its infancy, the team spend their time combing files, archives and microfilms for information. “The discipline with which they went through material was particularly remarkable,” says Ruffalo, who got to spend 10 days shadowing Mike Rezendes, the Globe reporter he plays. The film begins as allegations resurface concerning a now-defrocked priest, Father John Geoghan, who is said to have molested more than 80 boys, many of whom have since been represented by Tucci’s lawyer. Stories had previously been run but no follow-ups pursued, until the Globe’s new chief Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber), a Florida native and the first Jewish editor of the paper, turns it over to the Spotlight team, run by Keaton’s veteran reporter Walter “Robby” Robinson. Other examples of abuse by fellow local priests are pursued, but as the team painstakingly compile the story, there is a gradual dawning realisation that this is not just confined to Boston. When a former Benedictine monk and mental health researcher tells the team over the phone that this might be a “recognisable psychiatric phenomenon” among Catholic priests, the camera pulls back, almost in horror, as the reporters become aware that this is just the tip of the proverbial iceberg.

To the film’s credit, there are no sensationalistic flashbacks to scenes of abuse or depictions of the Catholic Church hierarchy as cartoonish villains. “It’s certainly salacious what had happened, but like any true great reporting, it allows us to get there by factual, dispassionate, discerning inquiry,” says Ruffalo. “The story will have a deeper reach into the world because of that.” For all the Spotlight team’s tenacity, mistakes are made and details overlooked. “Reporters are always talking about how they’re feeling around in the dark,” says McCarthy. “They’re always looking for that one thing. This is an example of well-funded professional journalists doing their job at a very high level, and the result was quite amazing, but they miss things along the way.” Human error is one thing, but Spotlight also focuses on a much darker area; as the reporters piece together the case, they begin to ask, “What took us so long?” After all, evidence was there, even buried in their own archives. According to McCarthy, that speaks to a much bigger topic – “questions of deference and complicity, both on an institutional and societal level”. Or to put it more bluntly, “people know but they don’t act”. In Ruffalo’s eyes, Spotlight emerges as a universal story. “It’s not just about the Church, it’s about us. What happened in Boston happened all over the world. And what happened essentially was that everyone in the community in one way or another turned an eye away from the truth. “It wasn’t just the Boston Globe, it was the police department, it was the politicians, it was the Catholic Church … that’s what this story is about. All of them, at some point, were not willing to look at the truth.”

To date, the film hasn’t triggered any negative outcry from the Catholic Church. At the US Conference of Catholic Bishops last September, guidelines were drawn up to help bishops deal with the emotions the film might stir among their parishioners. The consensus was to show the Church has changed since the 2002 scandal, that predators will be immediately removed from the Church and any abuse complaints will be reported to civil authorities. At the apex of the Catholic Church, Pope Francis even formed the Vatican’s Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, led by Boston’s Cardinal Sean O’Malley, to develop programmes to help bishops deal with sexual abuse cases. McCarthy calls it a step “in the right direction” but notes that organisations such as SNAP (Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests) are sceptical and want full and open apologies. “I think they’re looking for those kind of reparations,” he says. Certainly the problem has not gone away. Three American bishops were removed from their posts in the first half of 2015, something McCarthy is not surprised at. “This was a problem that existed for centuries, if not decades, and there’s no reason to assume this started in the ’50s and ’60s. It’s been going on for a long time and it’s going to take a long time to clean up.” Thanks to Spotlight, that arduous road has been impressively illuminated. Spotlight opens on February 18

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.