|

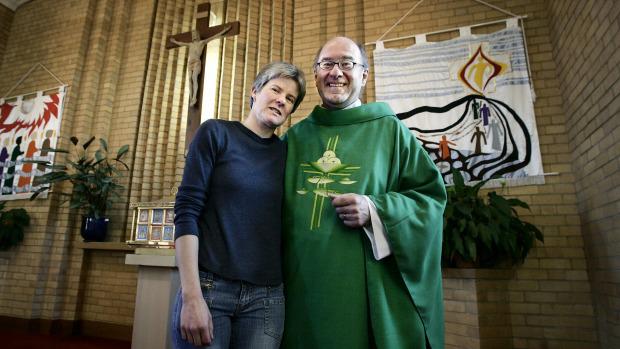

Why did a priest equate the 'sin' of a woman's adultery with paedophilia?

By Ruby Hamad

This week, a Melbourne Catholic priest compared priests who sexually abuse children to women who have extra-marital affairs. Apparently trying to make a point about mercy in the face of public outrage, Father Bill Edebohls, head of schools in his parish in East Malvern, referenced the tale of the adulterous woman spared from stoning by Jesus with the words, "He who is without sin. Let him cast the first stone at her." "For our generation, where adultery is not regarded as a crime – and many have lost the moral sense of the destructive harm adultery does to family and community... we probably don't get the power of the gospel story," he wrote. "Remember this was a sin, a crime that carried the death penalty... Maybe to get the real drama and effect of the story we ought to replace the adulterous woman with a paedophile priest. Then we might begin to understand the mob eager to stone and the outrageous and profligate mercy and compassion of God ever ready to forgive," he concluded. It's not the first time a clergyman's words have minimised clerical child abuse by reminding everyone that women are the real enemy; Cardinal George Pell once called abortion a "worse moral scandal than priests sexually abusing young people." We shouldn't be surprised. An institution as deeply patriarchal as the Church relies on the ostracism of women for its existence. Women cannot be priests and they hold no high-ranking positions. But the inappropriate equation of a woman engaging in consensual adult sex to a priest molesting a child is no accident. It is the product of a long history of casting female desire as dangerous and destructive; so dangerous that is was once worthy of death. It is also a telling reminder of the contempt patriarchy has for women - especially sexually active ones - and its consequences. If there is one thing that unites deeply patriarchal institutions and cultures across the world, it is the special hatred reserved for women who have sex. But it is not only women who suffer for this contempt. In its zeal to control women's sexuality, this hatred has spawned unrealistic restrictions on where, when, and with whom people can get it on. Priests, of course, can neither marry nor have sexual relations with women. This sexual repression is dangerous. Taboos on sex do not stop men from seeking or having sex. But they do increase the likelihood they will look for sexual release in inappropriate places. Leslie Lothstein, a therapist who treats abuser priests, argues that, because priests often enter the seminary in their early teens, they "miss a critical passage of maturation — first-time sexual experimentation". Imprisoned by this stunted sexual growth, "such men may be driven emotionally to claim and possess their past unexplored adolescent territory that the rules of a celibate priesthood had placed out of bounds". This places young people - mostly boys - in their care at risk. Northern Pakistan, seemingly light years away from the inner machinations of the Catholic Church, sees women banished from the public eye. Here, homeless boys are the highest risk group for sexual assault. "A woman is a thing you keep at home," says "Ejaz", who features in the documentary Streets Of Shame. "You can't take women out because people stare at them - they're useless things; you have to show propriety and chasteness with them. You can take boys around anywhere with you and it isn't a big deal." It's a similarly tragic situation in Afghanistan, where gender segregation is strictly enforced, and sex before marriage is both illegal and culturally taboo. It is in this sexually stunted climate that the tradition of dancing boys, bacha bazi, has flourished. Bacha bazi are young boys who are kidnapped or sold by their impoverished parents to powerful and rich older men, including warlords, politicians, and military personnel. Dressed in women's clothing, the boys are made to sing and dance for their overlords who rape them. In this rural region, the taboo on women's sexuality has rendered women unclean, and sex with them only a marital duty. As local men put it, "Women are for children- boys are for pleasure." This is what happens in a patriarchy that demonises women's sexuality. This is how contempt for women warps the minds of men. The stain of sex is for women to bear; it is their bodies that are loaded with shame, it is their freedom that is curtailed. Adult male desire, on the other hand is not only seen as natural but inevitable; women are theirs to use for procreation and young boys for fun. The shaming of female desire is so strong it has literally created conditions where the rape of adolescent boys by adult men is preferable than consensual sex with women. And where women who express desire are regarded as sinful as predatory priests. Both dancing boys and child sexual abuse by clergy have a long history. In both cases, women are pushed to the sidelines in the lives of men. In both cases, an aura of respectability is maintained while children suffer behind the scenes. And in both cases, the abused grow up to be the abusers, keeping the cycle of violence and shame turning into infinity. Is there a way to overcome this? Of course men must take personal responsibility; not every priest molests alter boys and not every Afghan man takes a bacha bazi. But we also need to be aware of how sexual repression creates a stunted environment that treats sex as a power play and can place children at risk. Child sexual abuse still happens in the Church today, but, as some priests demand the right to marry, and women demand the right to become priests, desegregation within the Church is a step forward. Meanwhile in Afghanistan, change hinges on the rule of law; warlords and politicians who have bacha bazi must lose protection and the inroads made in women's rights since the ousting of the Taliban must continue. Without a doubt, humanity's regressively hostile attitude to sex is one of our biggest failings. The conditions we place on it, and the judgement and scorn we reserve for women who have it, underpin so many of our global ills. These ills traverse religious, cultural and geographical boundaries with ease. And they find a resting place in the broken, violated bodies of children.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.