|

Loyola School on Upper East Side covered up teacher who molested seven girls in 1970s, 1980s — but victims can’t sue

By Michael O’keeffe

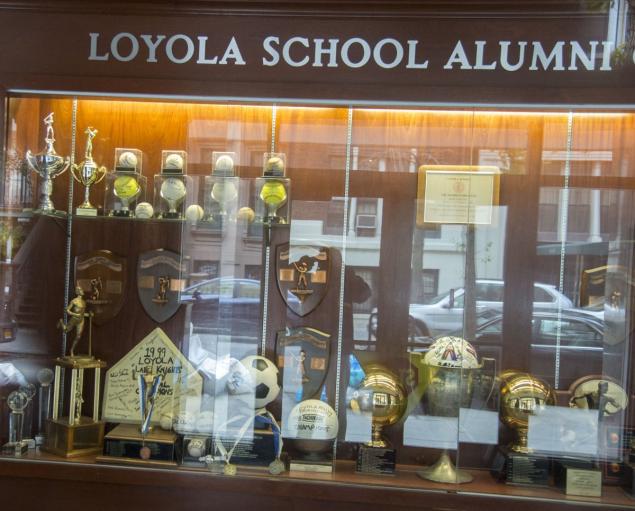

Louis Tambini was a legendary figure at Loyola, a history teacher, coach and athletic director who worked at the small Catholic school on the Upper East Side for more than 30 years. Tambini was also a creep who molested seven girls who attended the school in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Officials at the Jesuit-run school failed to notify authorities, parents or alumni when they learned about the sexual abuse allegations, according to a report commissioned by the current Loyola administration and prepared by the Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft law firm. But despite evidence that Loyola officials covered up the abuse for decades after they learned of the allegations in December 1982, the victims can’t file lawsuits against the school because New York’s statute of limitations expired decades ago. The statute of limitations in New York, considered one of the strictest in the nation, bars sex abuse survivors from pursuing criminal charges or civil damages after their 23rd birthday. “This report really does memorialize how an institution can use a strict and draconian loophole in New York State law to keep the matter quashed until the statute of limitations runs out,” said attorney Mike Reck, who represents one of the victims. Barbara Dorris of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, meanwhile, said the damning Loyola report provides a cogent argument for why statute of limitations reform is necessary. “This report is more proof that even now, Catholic officials work very hard — and usually with success — to keep child sex crimes and coverups covered up,” Dorris said. “That’s one reason why New York’s archaic, predator-friendly statute of limitations must be reformed and why every person who saw, suspected or suffered abuse and coverup should call secular authorities, not church officials.” The six-page report issued April 15 and prepared by Cadwalader attorney Ken Wainstein and two associates concluded that Tambini, who died at age 70 in 1999, could have been prosecuted for sexual abuse. All of the incidents took place at the school; one of the girls was molested as Tambini taught a class. “The actual abuse was generally similar in each instance,” the report said. “Each victim reported that Tambini approached her from behind and rubbed himself against her backside in a state of arousal.” Loyola administrators learned about the abuse in December 1982, according to the report, when a freshman told two faculty members that Tambini had abused her. The parent of another girl also reported at that time that Tambini, a popular teacher who coached the school’s baseball, basketball and girls’ volleyball teams, had “inappropriately touched her.” Tambini was fired — but he was allowed to continue teaching and coaching until the end of the 1982-1983 academic year. Administrators did not call the police or notify parents or alumni about the allegations. Some of the victims, the report said, were frustrated because Loyola officials continued to laud him publicly long after his dismissal. Tambini’s name continued to grace the school’s annual award for outstanding male athlete until just recently. Current Loyola president Tony Oroszlany learned about the sexual abuse allegations against Tambini in April 2015 when one of the alleged victims posted about it on Facebook. The report says Oroszlany later discovered a letter written in the mid-2000s by one victim that described Tambini’s abuse and “the school’s inadequate and insensitive” response. An administrator forwarded the letter to police, but the cops declined to investigate because Tambini was dead. Loyola officials yet again failed to notify parents and alumni or issue a public statement seeking additional victims. Loyola officials commissioned the Cadawalader investigation in May of last year. The school also provided funding to the victims for counseling and paid travel expenses for victims to meet with Wainstein and his investigators. “From my perspective the current administration’s response to learning about this misconduct was an example of how every school should respond to sexual abuse allegations,” Wainstein said. Despite Loyola’s admissions, the victims won’t be able to use the courts to learn what school officials knew about Tambini’s abuse and how they responded to it, Reck said. The victims won’t be able to pursue full disclosure without passage of the Child Victims Act, which would eliminate the statute of limitations in sexual abuse cases and open up a one-year window for older victims to pursue litigation. “This is an investigation that could have and should have been done a decade earlier,” Reck said. “I think they are doing the right thing because of pressure from survivors and their advocates.” Contact: mokeeffe@nydailynews.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.