|

St. George's sex-abuse scandal: Rev. 'Howdy' White's trail of trauma

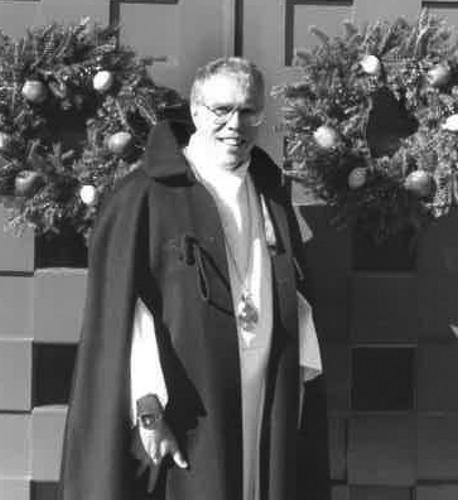

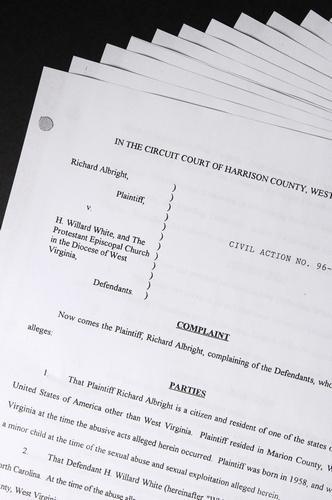

By Karen Lee

In December 1966, the Charleston Daily Mail noted the ordination of Howard W. White Jr. as an Episcopal priest in West Virginia. White, like all other Episcopal ordinates, vowed to follow the teachings of Christ and be "a wholesome example" to his people. White's first assignment, at Trinity Episcopal Church in Martinsburg, West Virginia, lasted less than a year. He moved, and moved again, from parishes to elite boarding schools, from prep schools to churches, from state to state and within states. New Hampshire. Rhode Island. Virginia. North Carolina. Pennsylvania. Along the way, White's accusers say, he left a trail of wrecked and broken lives. The allegations of sexual abuse span decades and distance. A godson. A boy who says he lived with White in a rectory and fled to the streets. A teenage parishioner who says White molested her at the same church. A former St. George's School student. All between 10 and 15 years old. Two of whom have recently stepped forward in North Carolina. In 1974, St. George's in Middletown quietly fired the Rev. "Howdy" White after he admitted sexual misconduct, but did not report him to authorities despite a mandatory reporting law. The St. George's victim, who chooses to remain unnamed, told The Journal in February that White mentored him when he was barely 15. He was a slight, lonely boy -- lured, he says, by White's charisma, attentiveness and Porsche. He says White raped and abused him in a camper in Canada, in Boston hotel rooms and in White's parents' house in West Virginia. Then-headmaster Anthony M. Zane sent White on his way with a letter stressing that White "should not be in a boarding school and should seek psychiatric help." Zane added, "I wish you well." White, it has been established, is one of half a dozen former employees entangled in the sex-abuse scandal at the elite Episcopal prep school that dates to the 1970s and '80s. White has not been charged with a crime. Efforts to reach White, by phone, email, registered letter and through a friend, have generated no response. White, now retired in Bedford, Pennsylvania, is under a bishop's orders not to attend the St. James Church where he has recently served, or to leave town without telling her. Under terms of his administrative leave: He is prohibited from being alone with minors. He cannot perform any priestly functions. He cannot represent himself as a priest in good standing, "although he may represent himself as a suspended priest, and as having been ordained in the Episcopal Church." Two months ago in North Carolina, Forrest Parker Jr. read a Providence Journal news story about White reprinted in a local Asheville paper. The story reported that a woman had just brought a complaint in Waynesville, North Carolina, alleging that White abused her at Grace Church in the Mountains in that town when she was about 15 years old, in the mid-1980s. The woman told The Journal she subsequently attempted suicide and nearly succeeded. The story left Parker dazed and overwhelmed. He picked up the phone and called a Journal reporter to tell his own story about White. Parker, 46, says he lived with White for about four months, and that White raped and abused him in the rectory and on road trips. Parker grew up poor in a hollow -- "like a dip in the mountains," he said during one of a series of interviews. He and his three brothers lived in foster and group homes; they lived intermittently in a trailer on a pig farm with their mother, who was dying of cancer, and an alcoholic, abusive stepfather. "We had water come out of the spring up side of the mountain. We ate a lot of beans and potatoes," said Parker. "We had to go to Christian charities to ask for help in getting my mother's colostomy bags. We didn't have money to pay for them." After their mother entered a nursing home, Parker and his brothers bounced among foster homes, group homes and emergency children's shelters. At one point they ran away: Waynesville police caught them and put them in juvenile detention, "like a kid jail," he said. Finally, Parker says, "they split us up." A social worker from Haywood County Social Services "just left me there with White." He lived with White in the rectory "within spitting distance of the church." At first, Parker believed he'd gotten lucky. White had money. He bought him gifts. A mountain bike. Clothes. Fancy meals. "He had suits tailor-made for me. I stood on a stool -- they measured my arms and legs. It was like you see in a movie." A yellow suit. A blue suit. "I wore the suits to church" several times a week. He also remembers playing with White's sheepdog, Mopsa. White took him on road trips, including to White's parents' "Victorian-type" house in West Virginia, where guests drank cocktails and praised the Lord. Within days of Parker's arrival, White bought a new Ford Taurus station wagon. They drove to Washington, D.C. "He gave me traveler's checks. It's the first time I ever seen them," Parker said. At the Smithsonian museums, "we saw the diamonds, and the airplane hanging from the ceiling." "The Smithsonian was fun during the day, but you didn't want to go back to the hotel room at night because you know what was coming." That, says Parker, marked the first time White raped him. Back in Waynesville, White "would lay in the bed with me. I would turn my face away from him and he would …. rub up against me and sleep with me … " On July 4 that year, White raped him again, when they visited White's friends to watch fireworks by a lake, Parker says. After that, Parker ran away and reconnected with his youngest brother. "If it wasn't the day I turned sixteen it was the day or two after that. Me and my brother went to live on the streets." "We did what we had to do. We went through trash cans to get food." They rifled for quarters at coin-operated car-wash vacuum cleaners. They smoked pot and drank. "Nobody came looking for me. You would think they would have." He went back once to get his clothes and his bike. White refused, saying 'You're on your own,' or something like that," Parker recalled. Out on the street, he used cocaine and heroin. He was in and out of county jail for minor offenses. He spent about 10 months in prison on a DUI. Today, Parker says he's clean and is training to be a counselor at the same drug-treatment center that helped him. He has also met with Waynesville police regarding his allegations against White. His attorney, Leto Copeley of Copeley Johnson & Groninger PLLC in Durham, said Friday that the Haywood County social services department confirmed that a file exists for Parker. She also said she has no doubt about his story because of its specificity. Waynesville Det. Lt. Chris Chandler said Friday, “We are proceeding with the (criminal) investigation" into two cases: Parker's, and that of the woman who reported that White molested her in the mid-80s' at the church. At around the same time -- apparently after Parker ran away -- another boy came to live with White at the Grace Church in the Mountains rectory, and, according to half a dozen community members may have been adopted by him. The Journal located that boy, now in his 40s. His wife said he didn't want to talk. Former classmate Hunter Pope says, "The first time I knew [the boy] was when he was with Howdy at my grandfather's funeral. I was probably 14 or 15." Pope ran cross-country with the boy. He recalls him as a good student who "blossomed more and more every year" when he lived with White. As for the allegations against White, "Like pretty much everyone else -- my whole family -- it's very shocking, and heartbreaking, too," Pope says. "I have nothing but positive things to say [about White]. He was a delightful guy. He was extremely intelligent, and like I said, I liked his dry wit. He made people chuckle quite a bit during his sermons. He had some levity" even while discussing serious topics. "He brought the church a new pulse," said Pope. "We got a good heartbeat going again." During his years as rector, White also drew accolades in "Grace Notes," the church newsletter, including for his "Tuesday Discovery" after-school classes with children. Longtime parishioner Mary Elizabeth Staiger says she recalls that White adopted the boy, "who came from very, very poor circumstances." Staiger also recalls that an artist who painted the walls of the children's nursery included an image of White "in his robes, with his sheepdog," amid depictions of animals and trees. On Dec. 20, 1987 -- 13 years after St. George's School fired White but did not report his sexual abuses -- the Haywood County court swore him in as a guardian ad litem, a trained community volunteer who is appointed, along with a guardian ad litem attorney, to investigate and determine the needs of abused and neglected children. According to court administrators, White had to pass a criminal background check, undergo a screening interview, provide three references, and complete pre-service training. Having done so, he was appointed to advocate for a child’s best interest in juvenile court. In 1996 -- while White was still rector at Grace Church in the Mountains -- Richard "Tim" Albright, who said he was White's godson, sued him and the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of West Virginia. Albright's suit was based on recovered memory of a sexual assault around 1969 that allegedly took place in a camper at Oral Lake, West Virginia -- roughly three years after White's ordination. Albright, now 57 and a musician in Florida, spoke by phone after The Journal published a story about the lawsuit in February. Recalling that night, Albright said White demanded he get in bed with him in the camper. Two boys shared another bed nearby. Albright, around 10 or 11 at the time, says he tried to fight White off. White "threw me to the floor" and said, "What's wrong with you? The other boys like it." "The number he pulled on me was just total psychological, to keep me from saying anything. He told me everybody else liked it and I better shut my mouth …" Albright adds, "He changed my life forever. I didn't know how to deal with what happened … he took my childhood from me. He took my self-esteem." Albright said he drank for 23 years; he's been sober for 24. Albright's lawsuit alleges that White and the Church conspired to cover up White's abuse of him and that they were "motivated by their desire to prevent public knowledge, criminal prosecution, disgrace and scandal, and by their desire to obtain and/or retain the active service of a priest." And as such, the Church -- "upon discovery of Defendant White's molestation of children … systematically and clandestinely suppressed knowledge of the misconduct of Defendant White and continued to appoint him to permanent, temporary and substitute assignments with The Diocese of West Virginia and elsewhere, without reporting the criminal sexual misconduct to law enforcement authorities" or notifying parishioners as to White's "history and propensities for sexual molestation of youth …" The circuit court of Harrison County dismissed the case, saying it was filed too late, beyond the statute of limitations. Two years later, the state Supreme Court of Appeals upheld the dismissal. White and the Church were neither absolved nor found guilty; the merits of the case were never discussed. In 2002, White resigned from his volunteer guardian ad litem service. He told the court he had lost interest. Four years later, he retired to the borough of Bedford, Pennsylvania, where he had family. He became a volunteer priest, filling in for Sunday worship services at St. James Episcopal Church in Bedford. In December, 2015, on the cusp of White's 50th year since his ordination, a story broke in The Boston Globe about systemic sexual abuse at St. George's School. At a subsequent Boston news conference, lawyers for an alumni victims' group, "SGS for Healing," publicly identified White and a former choir director as among the half-dozen unnamed perpetrators in the school's initial investigative report. The Rt. Rev. Audrey Scanlan, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Central Pennsylvania, put White on administrative leave. Scanlan said parishioners have been bringing him meals and sending cards. And at the request of the Rt. Rev. W. Nicholas Knisely, Episcopal Bishop of Rhode Island, the Church has launched an ecclesiastical investigation. The Rev. Canon Michael Buerkel Hunn, canon to the presiding bishop for ministry within the Episcopal Church, said: "We really support what Bishop Knisely has been doing, in terms of both collaborating with law enforcement and helping the truth come out and be told." "We really believe in confession and repentance," Hunn said. He added that the Episcopal Church, since the 1990s, has been strictly applying its "Safe Church" policies, requiring training for clergy, parents, volunteers and children. In Rhode Island, state police are close to wrapping up their St. George's investigation for review by the Rhode Island Attorney General's Office. A third-party investigator commissioned by St. George's and SGS for Healing also plans to issue a report. He was hired after the alumni/victims' group raised concerns that the first investigator had a conflict of interest. The school's initial investigation found that six staffers sexually abused 26 students. Lawyers Eric MacLeish and Carmen Durso say they have consulted with more than 40 alleged victims. State police say a primary focus is why St. George's did not report known and alleged perpetrators to authorities. The school has admitted it "failed on several occasions to fulfill its legal reporting requirements." "I think people would look at it and they'd say the school should be held accountable if they knew of the behavior," says Rhode Island State Police Maj. Joseph F. Philbin, detective commander. "Were the proper people notified of this misconduct? What steps did they take, if any? Was the student body notified? Were the parents of the student body notified?" Philbin said. The failure to report sexual abuse, or known sexual abuse, can be prosecuted as a felony, said Philbin. The school has expressed its "deep regrets," calling it "heartbreaking to hear these reports and to contemplate how St. George's students have experienced abuse and suffering as a result of their time at the School." It has pledged "to do all we can to support and help them in their efforts to heal." The Rev. Russell W. Ingersoll, a friend who knew White since they were dorm masters at St. Paul's School in New Hampshire in the late 1960s, said he was "blown out of the water" when he heard the accusations. White is his daughter's godfather. "I read it as a very difficult situation for him -- tragic for him and others if it is true," Ingersoll said in a telephone interview from his Arizona home. "He's suffering." White maintains his innocence, said Ingersoll. "He says it's not truthful … But I don't know. I don't know what to make of it." Ingersoll said he recruited White to be chaplain at Chatham Hall School for Girls in Chatham, Virginia, in 1978. That was four years after White was fired from St. George's. In an April 15 interview, Ingersoll said he was "certain" he called Anthony Zane, then St. George's headmaster, to ask about the circumstances of White's departure. He said Zane said nothing about allegations of abuse or that White had been fired. On April 21, when reporters called Ingersoll back, he said he felt his earlier comments were "misleading." He said he had "no memory" of speaking with Zane. "The fact that I don't remember the content of the conversation tells me it's more likely I wouldn't have called," Ingersoll said in the latest interview. After previously declining comment, Zane said Friday: "Reverend Ingersoll -- I don't know what he says, but I never talked to him about Howdy White ... I never recommended Howdy White to anybody and nobody ever called me." Zane said he never kept track of White after he fired him: "I did not follow through. When he was gone, he was gone." Ingersoll, though, said there is one thing he's sure of. "If someone told me [that White had been fired], I wouldn't have hired him." Contact: kziner@providencejournal.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.