|

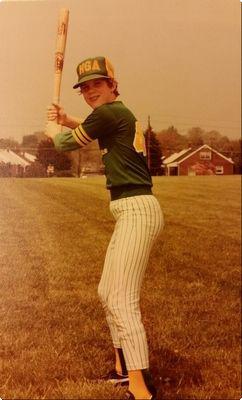

Silent Struggles: Thomas Humma

Reading Eagle

As state lawmakers debate a plan to make it easier for victims of childhood sexual abuse to seek justice, abuse survivors are coming forward to tell their stories. The day is seared into Thomas Humma’s memory.It was the moment, he said, that he finally broke free of the priest who snaked into a central role in his life only to sexually molest him.Though Humma hasn’t told his story publicly until now, parts of it have been recounted in media reports, at press conferences, even during state legislative sessions.His story is intertwined with that of his childhood friend Mark Rozzi, who’s since become a state lawmaker representing part of Berks County and an advocate for abuse victims.Their alleged abuser, Edward R. Graff, died in 2002 while awaiting trial in Texas on charges he abused a 15-year-old boy there.Humma, who grew up in Reading and now lives on the West Coast, figures Graff pushed his luck the day he took both boys together into the rectory at Holy Guardian Angels in Muhlenberg Township. At the time, Humma was 12, and Rozzi was 13.To Humma, Graff’s transition from surrogate uncle to sexual predator had been seamless and subtle. It wasn’t until that day that he was suddenly hit with the reality of what was happening.He remembers lying naked and half-drunk on Graff’s bed with pornography playing on the television as Rozzi darted out of the shower, picked up his clothes and motioned that it was time to leave.“I’m in the room and Rozzi comes running,” Humma said. “And I saw pure fear in his eyes. And a switch went on.”Humma said he would later learn Graff had raped Rozzi in the shower, the act that pushed the abuse over the edge and cost Graff both boys’ trust. But then in the room, Humma saw Rozzi, the alpha male in his group of friends, broken and frightened like a little boy.“He didn’t say anything to me,” Humma said. “He just looked at me. It was the scariest thing that I have ever dealt with.”Rozzi confirmed the events of that day.The boys made a pact never to speak about what had happened. The secret drove a wedge between them, Humma said, and the once-close friends became distant acquaintances.It wasn’t until both were in their late 30s and ready to talk about their abuse that they began to repair their friendship.Humma promised his parents when he eventually told them about the abuse that he wouldn’t go public with his story until after his grandmother’s death. She was a devout Catholic and he said he has no doubt the heartbreak would have killed her. Master manipulatorHumma was a seventh-grader at Holy Guardian Angels school when Graff arrived at the school and parish. Graff would pay Humma and other boys to rake leaves and do other chores around the campus. Graff and Humma would talk about football and horses. Soon, Graff was a regular guest at Humma’s family cookouts. The family trusted him.“He was a master, there was no doubt,” Humma said. “He was a master manipulator.”It wasn’t long, Humma said, before he and Graff were taking trips together.They would go to Penn National Race Course near Harrisburg where Graff would bet on the horses and give Humma money to do the same. Graff gave Humma a snap-brim newsboy cap to wear, saying it made the boy look older. Humma said the sight of such a cap still triggers painful flashbacks. So does the smell of cigar smoke, which permeated Graff’s car and rectory.Humma said Graff started to sneak him into the rectory, telling him that he wasn’t supposed to be there and it must be kept secret. They would drink wine and talk about sports. Humma said he was honored and flattered that Graff treated him like an adult. He felt special.The transition happened slowly.First, he said, Graff would show him pornography and talk with him about sex, telling him he needed a teacher. That led to Graff masturbating him while touching himself, he said. That continued for six months.Humma said he was uncomfortable but didn’t know how to respond. He said Graff would ply him with alcohol during the visits and he’d been taught to trust priests. When he questioned Graff, he said Graff responded that he was acting as “an instrument of God.”“The mental gymnastics that he was forcing us to go through when we were 12 or 13, it’s hard to describe,” Humma said. “It was almost like psychological warfare.”Humma said he was finally free of Graff’s abuse after running out of the rectory with Rozzi. But it wasn’t the last he saw of the priest. He said Graff approached him days later and threatened to destroy his family if he ever spoke of what happened.For the next few years, he said, Graff would periodically show up uninvited and unannounced while Humma was home with his parents. Humma suspects that was to gauge his parents’ reaction and verify they didn’t know about the abuse. Facing his abuseNow 44, Humma figures he’s built himself back up 80 percent of the way. But the abuse is still something he deals with on a daily basis. He’s spent years in therapy and tried all sorts of medication, each with its own litany of unpleasant side effects. He’s remained a bachelor and moved often, reluctant to get too attached to people and places. His personal relationships have been strained.“I let people close,” he said, “but not super close.”For years, Humma said, he kept his abuse a secret. He was worried what people would think about him and about Graff’s threat.He didn’t even tell his parents until he was in his mid-20s. For them too, he said, the feelings of betrayal have been a strain.He was in his late 20s when he finally began to face his abuse and seek help. He was living in Michigan then and was sitting in Sunday Mass when it all hit him. He began feeling sick and walked out of the church. He hasn’t been back to Mass since.At that time, Humma said, he felt broken. He had been self-medicating with excessive drinking. He couldn’t sleep. He suffered from chronic stomach problems.So he began counseling. And he got sober.That was shortly before the Boston Globe’s 2002 investigation into the Boston Archdiocese cast a national spotlight on sexual abuse by priests and its concealment by church officials. Humma followed the coverage of other victims’ stories.“You get vindicated through the media breaking stories about that parish in this city,” he said. “But you’re still by yourself because you can’t talk about it. You’re not alone, but you’re on an island.”That same year, Graff was arrested in Texas and charged with molesting a boy there. Texas authorities said at the time that there were reports of at least 15 other victims of Graff in Texas and 12 in Pennsylvania. “They could have just put Graff out to pasture,” Humma said of church leaders. “But they didn’t.”Humma contacted an attorney representing the Texas boy’s family in a lawsuit against the Allentown Diocese, to which Graff was still connected after his move to Texas. Humma agreed to go on the record and send a signed statement detailing his alleged abuse.In 2003, the diocese announced a $275,000 settlement with a Graff victim, who was later confirmed as the boy from Texas. Pushing for justiceSince taking office, Rozzi, a Muhlenberg Township Democrat, has spearheaded the push to give child sex abuse victims more time to confront their abusers and organizations that shield them in court. The bill he’s championed would end time limits for criminal charges. It would also extend the deadline for victims to file lawsuits and allow all victims up to age 50 to file lawsuits, even if their earlier deadlines have passed.As the state House prepared to vote on the bill earlier this year, Allentown Bishop John O. Barres penned a letter to church faithful, opposing the plan and detailing the diocese’s response to abuse.“We have responded to the survivors and their families who have come forward with compassion and support to help them heal,” Barres wrote. “No matter who in the church committed the crime against them, or when the crime occurred, we make counseling and medical treatment available.”Humma said he shook his head with disbelief as he read the letter. The diocese would have known about his allegations of abuse as early as 2003 because of the statement he gave. But he said church officials didn’t reach out to him until 2010.At the time, he and Rozzi had been hounding state lawmakers and asking them to overhaul the time limits for abuse victims. It was two years before Rozzi would run for state representative. But Rozzi had spoken to the Reading Eagle on May 7, 2010 about his abuse.The diocese’s victim assistance coordinator emailed Humma on May 12, 2010, to offer her contact information. That came in response to an email Humma had sent to state lawmakers referencing the Eagle column about Rozzi and saying he was also abused by Graff.Humma was contacted again five months later by a man who identified himself as a private investigator hired by the diocese. His letter, which was sent to Humma’s parents’ address, referenced Humma’s 2003 statement.Diocese spokesman Matt Kerr confirmed that in 2003 the diocese received Humma’s statement from its insurance company, among other documents related to the Texas settlement. But he said the diocese didn’t have Humma’s contact information until 2010, when it obtained his email and reached out to him.He said the diocese’s response to abuse has evolved and services are offered to assist victims no matter when the abuse occurred.Humma said the diocese could have easily obtained his contact information.Humma enlisted the help of an attorney but never sued the diocese because the short window he had to file a lawsuit had passed. He’s hoping Rozzi’s reform effort is successful so his case can move forward.It’s not about money itself, he said. It’s about the church’s acknowledgement of what happened to him and the pain he suffered as a result.“The only thing that is tangible — because they’re never going to admit guilt — the only tangible thing you can hold is money,” Humma said. “The only thing they’re going to do is cut a check. But it’s a tangible thing that attaches to presumed guilt.”As more stories of abuse come to light, Humma said, he’s hoping there will be a tipping point in efforts to hold accountable those who are responsible.“There’s too much of this going on,” he said. “They can’t continue to paper over this thing without consequences.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.