|

A CROSS TO BEAR: Abuse victim seeks reconciliation with church

By Jeffrey Jackson

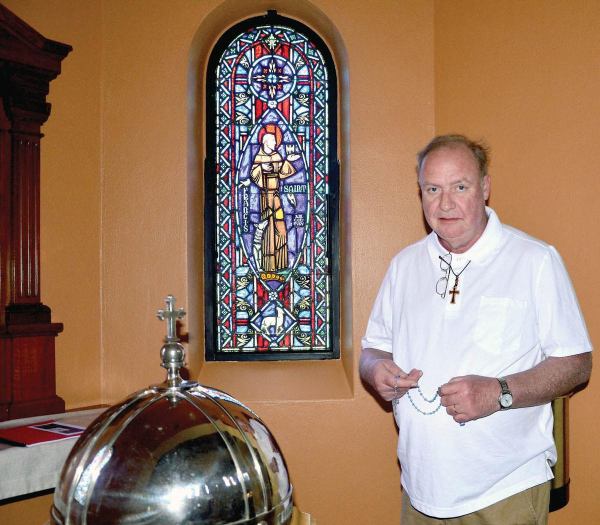

OWATONNA — Despite all that has happened, Gerald Lynch still wears a cross around his neck. “I still believe in Jesus,” said the 64-year-old Owatonnan. And Lynch still considers himself a practicing Catholic, though he admits that it’s not always easy to go to Mass, to be around priests or even to face Sunday mornings. Those things — “triggers,” he calls them — bring back memories he’d rather not face. “I want to be involved. I want to go to Mass on Sunday,” he said. “But there are circumstances within myself that make it difficult.” He paused. “I feel dirty,” he added Now, if there is anything Lynch is seeking in life, for himself and others like him, it’s reconciliation — reconciliation with the Catholic church, with the priest who sexually abused him as a young man, and, yes, with God. But Lynch realizes that the healing process for a person like himself who was abused by a priest can be a long journey: In his case, a journey of more than 40 years. And for Lynch, that journey began by admitting what happened to him. “The first thing I wanted to do was to deny it,” Lynch said. “But what you bury alive, stays alive.” Now, Lynch is on a mission to help others like himself to try to find that reconciliation. “People can harm you in the church, but that doesn’t mean that God is bad,” he said. “God didn’t cause this to happen.” A very Catholic life Jerry Lynch grew up on a farm outside of Bancroft, Iowa, during the 1950s and 60s — a town that he remembers as a Catholic community, a very Catholic community. There was a convent with 16 Franciscan sisters living there, a rectory with three priests, a Catholic grade school and high school, and, of course, a beautiful church. Not bad for a community whose population was hovering just over the 1,000 mark, he said. “Being Catholic was our whole being, our culture as well as our religion,” Lynch said. “Everything revolved around the church, other than a couple of bars.” And his own life, as well as that of his large extended family — four sisters, a brother and 96 first cousins, a very Catholic family — revolved around the church. And that wasn’t always easy. When Lynch was a freshman in high school, his father, then just 42, had a heart attack that nearly killed him. And young Gerald, the oldest boy of the family, had to take on many of the duties around the farm while still going to school, something he would continue throughout his high school career. Still, he found time pray at daily Mass and was honored as the “outstanding Mass server of the year” for his work during his senior year. So it probably came as no surprise to those who knew him that when it came time for him to further his education beyond high school, he entered the seminary at Loras College, a Catholic school in Dubuque, Iowa, with the intent of entering the priesthood. “Their whole personhood centers around the Catholic faith,” he said of his reason for wanting to become a priest. It wasn’t an easy road to travel. First, there were the times — a time of upheaval, as Lynch describes it, with the Vietnam War still raging and the protests that accompanied it. Even in the church, in the aftermath of the Vatican II Ecumenical Council, there were a lot of changes to which he and other Catholics were having to adjust. Then there were his own personal limitations — limitations to which he readily admits. “I was not the best student,” he said with a smile. “Learning was hard, and I was never a very good reader.” And even with the move to the vernacular in the Mass, he still had to learn Latin. “That was a killer,” he said. So he dropped out, though he didn’t give up his faith or his active involvement in the church. If anything, his involvement increased as he moved to Minneapolis and joined Servants of the Light, a Catholic charismatic organization that was growing by leaps and bounds during the 1970s. It was there that he met Father Bill Farrell, a Dominican priest who was one of the leaders of the community. It was Farrell, Lynch said, who abused him as a young man. “Father Bill stalked me,” Lynch said. “He had me over to the rectory, checking me out. Only in reflection do I realize what happened.” Betrayal It is in his poetry, penned some 40 years after the abuse occurred, that Lynch’s feelings — the guilt, the shame, the anger, lots of anger — come pouring out, sometimes raw, sometimes detached. Sometimes the titles of the poems —“Voices,” “Daybreak,” “The Quilt” — are vague enough, obscure enough, to hide the deep emotion within. With other poems — “Victim, Survivor, Thriver” or “A Sexual Survivor’s Prayer” — there is little doubt from the titles what the poems are about. Then there’s “The Betrayal,” a poem whose very title suggest what Lynch felt — what Lynch still feels — about what happened to him, a title that equates the actions of the church he loves with those of Judas. Then comes the first stanza, a stanza that would become like a choral refrain throughout a poem wracked with anger and pain. One word, one touch changed my life. Where is the outrage? He started writing poetry two to three years ago after he had attended a family reunion in Iowa with all those cousins, a reunion he attended with his daughter, born blind. Because she couldn’t see them, they couldn’t — or wouldn’t — see her. They talked around her and about her, but not to her. Lynch felt something very close to his own experience as a sexual survivor. The result was his first poem, “Am I a Statue?” Since then, he has written many more poems that he has self-published. And when you see him, he often has a copy in his hand or at least nearby. He has taken them with him to conferences, most recently last weekend to a national conference in Chicago of SNAP — Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. “Most people have difficulty stepping into the shoes of someone else,” he said. Especially, he added, stepping into the shoes of someone sexually abused. That, he said, is where he hopes his poems can help. “I’m trying to educate people about the devastation of sexual abuse by priests,” he said. And in poem “The Betrayal,” that devastation, at least for Lynch, is quite clear. Another stanza: Young, naïve, vulnerable; Stalked, targeted. Prey for insatiable sexual appetite. One word, one touch changed my life. Where is the outrage? The abuse The outline of Father William Patrick Farrell’s life is very brief: Born and reared in Rochester, N.Y. Entered the novitiate in Winona, Minn., in 1958. Ordained to the priesthood as a Dominican in 1965. He taught high school in Chicago and Dallas before moving to Edina, Minn., in 1971 to serve as associate pastor of Our Lady of Grace parish. It was during that time that he became involved with the Catholic charismatic movement in the Twin Cities. In 1973, he went to Louisiana as chaplain at Southeastern Louisiana University. But his health wasn’t good, mainly due to complications related to his diabetes. He was going blind. Still he kept active in ministry until he died on Ash Wednesday 1989. But according to Jerry Lynch, there is much more to Father Farrell’s story. As Lynch recalls it, the other leaders of Servants of the Light, the Catholic charismatic movement in the Twin Cities, got wind of Father Farrell’s sexual proclivities and went to his Dominican superiors, the provincial in Chicago, asking that he be removed. “In those days, that’s what the church was doing — move him to another place,” Lynch said. “So they moved him to Louisiana, to a different province.” It was in that move, Lynch said, that the abuse happened. By that time, Lynch, then 21, had moved to the Twin Cities and was very much involved with the Catholic charismatic movement there. And he was asked, along with another young man, to help Father Farrell make the move to Louisiana. “They didn’t tell me he was gay,” Lynch said. During the trip down, they twice stopped for the night. Both nights, Lynch shared a room — separate beds — with Farrell while the other young man had a room of his own. Both nights, Lynch said, he was awakened by the priest. “He woke me up naked in the middle of the night wanting sexual favors,” Lynch said. “I was tired, groggy, upset and confused. I didn’t know what to say, no clue.” Compared to other people’s experiences of sexual abuse by priests, Lynch counts his experience as tame. He wasn’t abused as a child. And, in fact, he says he rejected Farrell’s propositions of him. He even jokingly calls his experience “Priest Abuse Lite.” Yet to him, 40-plus years later, the experience is still devastating, to use Lynch’s description. “He was my confessor. He knew my vulnerability,” Lynch said. “I was 21, asking questions, ‘Do I date? Do I marry?’ I was a young man trying to find out who the hell I was. I shared that in confessions, and he knew my weaknesses. I was devastated at 21 — a vulnerable adult.” His age at the time of the incident does raise the eyebrows of some, coupled with the fact that, thus far, he has not found another victim of Father Farrell, though he’s certain they are out there. “I’m trying to track people down,” he said. It isn’t easy. The Bishop Accountability website — a website that tracks and documents abuse claims in the Catholic church — has no record of claims against Father William Patrick Farrell. And the provincial office of the Dominicans in Chicago has thus far not been able to locate any claims against the priest, though Bill Skowronski, director of communications and marketing for the province, said Thursday that they have not yet gone through all of the files. Likewise, neither the SNAP chapter in Minnesota nor the chapter in Louisiana had Father Farrell on its list. “This is not to say that he was never involved in abuse either here or in Louisiana,” said Frank Meuers, director of SNAP for southern Minnesota, “but as far as we know that abuse was never reported or a record made of it that has been made public.” In fact, it doesn’t surprise Meuers at all that Father Farrell’s name has not come up, particularly if he preyed only on adult males. “There is often more stigma attached to the adult cases [of clergy sex abuse],” Meuers said. “The victim beats himself up. ‘I should’ve known better. I should’ve walked away.’ The denial and guilt is smothering.” And because of that guilt, the victim will often blame himself over and over, Meuers added, to the point that the abuse goes unreported. Liturgy of reconciliation It was at a conference in Cambridge, Minn., in late April that Jerry Lynch first met Bishop Donald Kettler of the St. Cloud Diocese — a conference at which Bishop Kettler was speaking on the subject “Moving Forward.” Joe Towalski, the director of the office of communications for the diocese, explained in an email what the bishop meant by “moving forward.” “‘Moving forward’ does not mean ignoring people who have been hurt or forgetting about survivors,” Towalski wrote. “It means working together to bring about healing, reconciliation and justice in whatever ways are appropriate and possible.” It was at that point that Lynch came in. Lynch was attending the conference not as a speaker, but as an audience member who made his voice heard. “Bishop Kettler does recall the event and meeting Mr. Lynch,” Towalski said. “He was impressed by Mr. Lynch’s desire to help other people and move forward on the path to healing.” The bishop wasn’t alone. Jode Freyholtz-London — the founder and director of Wellness in the Woods, the mental health organization that hosted the “Learning through Sharing: Moving Beyond Trauma” conference — understands both Lynch’s guilt, depression and anger associated with the abuse and his desire to find some reconciliation. She’s seen it before. “I work with a lot of people who have trauma like Jerry,” she said. “For many of them, it’s not about blaming but about healing and bringing people back together again.” And she sees that in Lynch’s efforts. “He’s like a lot of abuse victims who are not trying to wipe out the church, but are wanting to be a part of the faith community,” she said. “I support people like Jerry who are coming forth to heal.” Not everyone sees it her way. Meuers said most of the abuse survivors he comes into contact with through SNAP Minnesota are Catholics — or rather, former Catholics — who have disavowed any relationship with the church. “They don’t feel any great affiliation,” he said. What they feel instead, he said, is bitterness and anger. And any attempt to forge any reconciliation under the auspices of the church, such as through a liturgy, would be, in Meuers’ words, “self-destructive.” “No one would come,” he said. But Lynch is not deterred. He still wants to see some sort of reconciliation between the victims of clergy sexual abuse and the church, perhaps in the way of a liturgy or Mass of reconciliation. It is a subject he broached with Bishop Kettler at the Cambridge conference. Towalski said that the bishop is open to such an event, though what that liturgy might look like and when and where it could be held still need to be determined. Lynch already has some ideas, having sketched out his own plan for a Mass of reconciliation, one that he hopes will be celebrated in the cathedral. The first paragraph of his plan contains this rubric: “The intent is to have this healing Mass celebrated in each parish of the diocese. It is very important to begin this process slowly, deliberately and grace-filled.” And the bishop? “Bishop Kettler believes victims/survivors should have a role in crafting a reconciliation liturgy. He is examining material he received from Mr. Lynch and others for such a liturgy,” said Towalski. “The bishop said such a liturgy would include taking responsibility and apologizing on behalf of the church for the abuse that has happened, and promising to continue ongoing efforts to prevent abuse and maintain safe communities for everyone.” As for Lynch, there is one other thing he would like. “I want to meet with the archbishop for a half hour and share my story,” he said. “I want to let him cry with me, if he is so compelled. Then I want to make my confession.” And what does he feel he has to confess? “My lack of faith,” he said. Contact: jjackson@owatonna.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.