|

HOW ST. GEORGE’S ATONEMENT FOR ITS SEX-ABUSE SCANDALS TURNED UGLY

By Benjamin Wallace

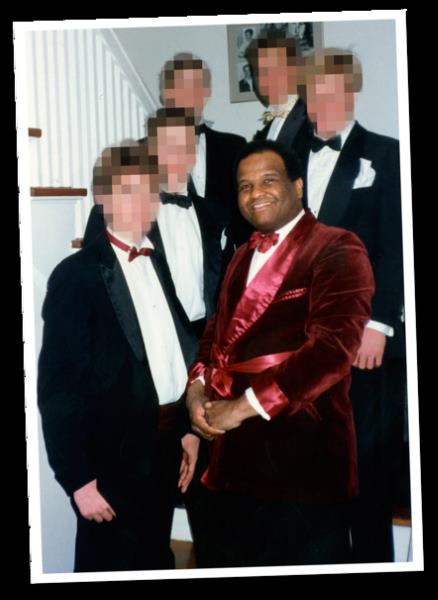

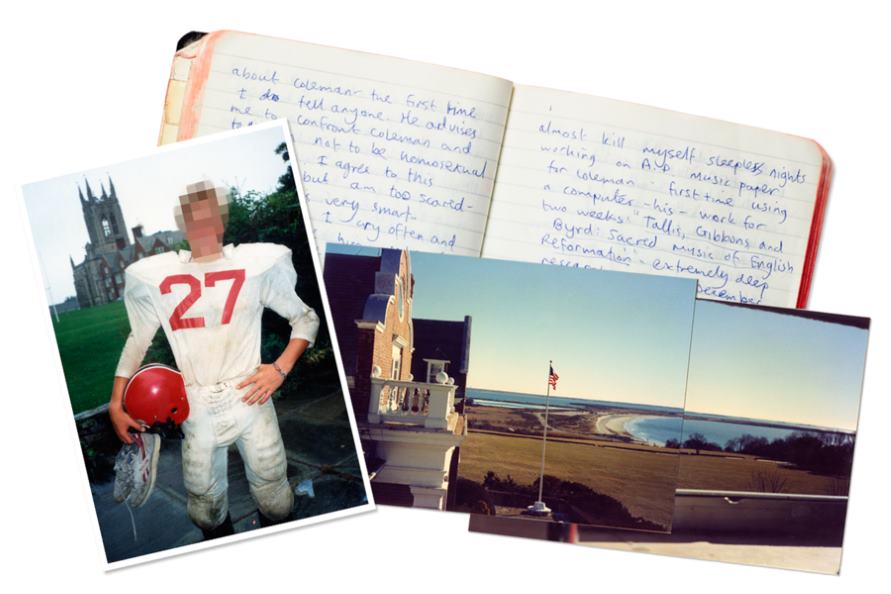

Yet another elite New England prep school is plagued by scandal—this time the picturesque seaside campus of St. George’s, which has only recently confronted a largely concealed, decades-long history of sexual abuse by predatory teachers, staff, and students. Benjamin Wallace interviews survivors, parents, and the headmaster to see how its search for healing brought fresh anguish. High-school reunions are fraught occasions under the best of circumstances. Hairlines and waistlines are appraised, marriages and careers compared, insecurities awoken, changes in status noted, old wounds poked: normally solid citizens regress to their adolescent selves. Then there are the worst of circumstances. Since December, when it broke into the open with a Boston Globe article and a televised press conference, St. George’s, an elite boarding school in Rhode Island, has been engulfed by a scandal over alleged sexual abuse spanning decades, with at least 40 alleged victims and a dozen alleged staff and student perpetrators. In this, St. George’s is only one among a snowballing list of prominent prep schools recently shaken by accusations of abuse, as one after another is forced to reckon with a shameful past. They include Groton, Horace Mann, Deerfield, St. Paul’s, Hotchkiss, Pomfret, Pingry, and Exeter. “Elite boarding schools turn out an outsize number of societal leaders,” says Whit Sheppard, a Deerfield graduate who has written about being a victim of abuse there and now advises schools on handling similar crises (including, for a short time, St. George’s). “This is the part of the story that no one wanted to talk about.” Now they are being forced to talk about it. Across the archipelago of prep schools clustered mainly in the northeastern United States, a truth-and-reconciliation process is fitfully unfolding as school after school sends letters to alumni acknowledging past abuse and asking if they, too, were abused. At St. George’s, the process has been especially tumultuous, with a vocal, mobilized contingent of alumni calling for the headmaster to resign amid a polarized atmosphere of mistrust. As the school’s annual reunion weekend approached in May, all-out bedlam threatened to erupt. In a private Facebook group, various St. George’s alumni put forward suggestions to hold “actions,” perhaps cordoning off locations where abuse had taken place with yellow police tape. One alumna proposed bringing a gun and burning the place down, upsetting fellow graduates; the alumna said she’d been joking. There was further talk of chaining themselves to the school’s front gates. After headmaster Eric Peterson sent a letter to alumni in April announcing that the school would hold a “Hope for Healing” event during reunion weekend to acknowledge the abuse that had taken place at the school, some survivors reacted angrily that Peterson hadn’t consulted with them beforehand. Two days later, the school backtracked and sent out another letter. This one, signed by board chairman Leslie Bathgate Heaney, said the event would no longer be held and that the school would consult with survivors about jointly organizing an alternative event. In a way, the same critical-thinking skills St. George’s prides itself on teaching had turned against their creator. This is a school that charges $56,000 in annual tuition and boarding fees, and also one which, like many of its peers, was founded not merely to educate but to provide moral instruction, to inculcate that character-forming ethos known as muscular Christianity. Betrayals of the 1970s and 1980s—which among other things were a very expensive and damaging hypocrisy—are now forcing a privileged corner of America to wonder what went wrong. And looming over that question is another, voiced by Hawkins Cramer, principal of an elementary school in Seattle and a 1985 graduate of St. George’s, who says he was abused there: “Where were the fucking adults?” “St. Gorgeous”St. George’s has always stood apart from other New England boarding schools by virtue of its magnificent setting on Aquidneck Island, on a peninsula directly across from Newport. On the Hilltop, as the campus is known, a student standing on the columned porch off the main formal tearoom, looking out on the playing fields that slope down to the sea, might easily imagine himself as Jay Gatsby come to life. St. George’s is one of the so-called Saint Grottlesex schools (along with Groton, Middlesex, St. Paul’s, and St. Mark’s), bastions of the Wasp establishment founded in the late 19th century to educate the sons of the Gilded Age elite. Graduates have included Mellons and Vanderbilts, Bushes and Biddles, Astors and Auchinclosses. It was patterned, like many other American prep schools, on English institutions like Eton and Harrow, and the legacy is visible in the stone neo-Gothic Episcopal chapel that towers over the campus, in the mandatory uniform (coat and tie for boys), in the terminology (9th grade is third form, 12th grade is sixth form). Over time, St. George’s developed a reputation for producing clubbable Establishment heirs more than brainy members of the meritocracy. “It was a school where at one time very wealthy families would send their not so bright kids,” says a late-80s graduate. “We’re not talking about Nobel Prize winners here,” echoes Daniel Brewster, a 1974 graduate. “If you’re part of an entity that relies exclusively upon its reputation for its status in the world, that reputation will be protected at all costs. At St. George’s, it was built on, frankly, the Social Register of a century ago. Otherwise you went to St. Paul’s, Andover, or Exeter.” F. Scott Fitzgerald described the students of St. George’s as “prosperous and well-dressed,” and by the 1970s, the school had acquired the nickname “St. Gorgeous,” not only because of the school grounds but also because its admissions policy seemed to select for physical attractiveness. Anthony Zane looked like he’d stepped out of the sort of oil portrait meant to be hung against wood paneling. Arriving at St. George’s in 1972, he was a patrician, old-fashioned headmaster, a hale man of action more than introspection, his Dalmatian always at his side. After the parents of a St. George’s student reported to the school in 1974 that sports-car-driving associate chaplain Howard “Howdy” White had raped their son, Zane expressed shock that the relationship had been more than “paternal.” He fired White but also seemed not to fully grasp the harm White had inflicted or the danger he represented. Zane didn’t report White to the Rhode Island State Police or the Department of Children, Youth & Families. When White contacted him shortly thereafter, seeking help, Zane responded warmly, saying that he would pay him an additional month’s salary and reimburse him for his moving expenses. He did add that “if you find yourself hard pressed in the future I suggest that you consider selling your Porsche . . . . I feel strongly that you should not be in a boarding school and that you should seek psychiatric help.” He asked White not to return to St. George’s “until one generation has gone through, that is, not for another five years.” White didn’t return, but he did go on to serve as dean and chaplain at Chatham Hall, a girls’ prep school in Virginia, and then as rector at a church in North Carolina from 1984 to 2006; state police are investigating an allegation that he molested a teenage girl there, and the Providence Journal located at least one other alleged victim from that period. (White is now retired in Bedford, Pennsylvania, where he is under ecclesiastical review by the Episcopal Church. He has not commented on the allegations.) St. George’s began admitting girls as boarding students in the fall of 1972, Zane’s first semester, but meaningful co-education would have to wait. When Anne Scott arrived as a sophomore five years later, boys still accounted for four-fifths of students. Little effort had been made to increase the number of female faculty, there was no girls’ locker room (girls had to change for sports in their dorm rooms), and the culture remained starkly masculine. The failure to diligently integrate girls was visible in the athletic training room, which despite serving both boys and girls was accessible only via the boys’ locker room and was staffed by an older male trainer, Alphonse “Al” Gibbs, a small, gruff navy vet with the smashed nose of a boxer. It was a back wrenched playing field hockey that sent 14-year-old Anne Scott to see 67-year-old Gibbs in October of 1977. “I’ll never forget the sound of the lock clicking,” she says. Gibbs “would start with something remotely in the guise of treatment and work up from there. He’d change the narrative from treatment and the thing wrong with you to your developing body, as someone who was a helper, a carer of your whole body.” Before the month was over, he had raped her, and he continued to do so for nearly two years. “I was that animal in the herd who got isolated out, and he was able to go really far with me.” She started calling her parents, crying and wanting to come home, but wouldn’t tell them why. She felt trapped. She didn’t have the language to say what was happening. (“We’re Wasps!”) “He’d tell me not to tell anyone—I’d get in trouble.” She says she developed an eating disorder and cut herself off from friends, sitting alone for hours in a place she’d found in the woods. Anne Scott wasn’t the only girl targeted by Gibbs. He smeared VapoRub on the chest of Kim Hardy Erskine (class of ‘80), then a sophomore basketball player, and at practices would “come up to his girls and kiss us in front of everybody, on the lips. He also gave me a gold necklace one year”—a chain with a heart on it. Joan “Bege” Reynolds, a sporty girl from a multi-generational St. George’s family, was a 13-year-old freshman when Gibbs told her to undress and get in his whirlpool, groped her legs “up to the private area,” smothered her with “really awful hugging and kisses,” and took Polaroid photos of her naked under a heat lamp. Katie Wales, a three-sport athlete with a torn-up knee and back, had a similar experience: “He’d show you how to dry off: ‘Lift your breasts, dry your private area. Let me make sure you’re cleaning yourself properly.’ It was awkward. But he has a medical patch on his shirt. He was a highly decorated medic in World War II. You figured he knew what he was doing.” She, too, was Gibbs’s photographic subject and had the additional humiliation of hearing things like “nice tits” from boys to whom Gibbs had shown the photos. Most of the girls didn’t report Gibbs, but Wales says she went to Zane in tears, and he “dismissed it as my imagination.” (Zane, now 84 and living in New Bedford, Massachusetts, has said it was he who approached Wales, after a senior boy happened to catch Gibbs photographing a naked girl with a towel over her face and reported him, and said that he never called Wales crazy.) In any case, on February 5, 1980, Zane fired Gibbs after a several-day investigation during which Zane interviewed a number of girls about their experiences with Gibbs. At least 20 students were abused by Gibbs during his seven years at St. George’s. (Gibbs died in 1996.) Why didn’t the school catch on to Gibbs earlier? Clearly, there were rumors circulating about him, even if they were expressed jokingly: in the 1979 yearbook, a caption under a photo of Gibbs with a girl read, “Mr. Gibbs, get your hand off my . . . Elbow.” As he had done with White, Zane failed to report Gibbs to any state agencies. (Zane told Vanity Fair that he had not been aware of any legal obligation to do so.) Upon Gibbs’s departure, Zane announced at a school assembly that the trainer had left merely because of a health issue. This may have been justified by concern for the privacy of the girls, but shockingly, the school gave Gibbs a pension as well as a letter of recommendation which described him as “most certainly competent” and attributed his departure from St. George’s to a “medical leave.” Gibbs even reappeared on campus a few years later, attending a cocktail party during homecoming weekend. “Zane pretty clearly was not interested in rocking the boat,” says Carmen Durso, an attorney representing a number of the St. George’s victims. “His idea was: You got a problem, you make it go away.” A Factory for Holden CaulfieldsIf Gibbs was enabled by institutional misogyny, a second set of students fell casualty to a laissez-faire interpretation of the school’s in loco parentis mandate, which mixed harsh discipline with near anarchy. At St. George’s, suspensions and expulsions were common, often the inevitable result of a tone set by the administration. “We bragged that you could fit all the rules of the school on one side of an 8 1/2-by-11-inch piece of paper,” says Bryce Traister (class of ‘86). “You could go down to the beach and smoke pot and drink and have sex and surf,” a late-80s grad recalls. “It was heaven.” The school became a factory for Holden Caulfields, alienated kids whose parenting had been outsourced to a not very nurturing place. Freshmen and sophomores were effectively in the care of the seniors who ran the dorms. It was a Darwinian environment, which several St. George’s alumni separately described to me as Lord of the Flies. Certain years, the hazing got way, way out of hand. In the fall of 1978, a senior made a freshman named Harry Groome stand on a trash can and pull down his boxer shorts, whereupon the older student sodomized him with a broomstick in front of several other students. It was neither a secret incident nor one that was taken seriously by the school: a later yearbook photo of Groome in a trash can was captioned: “It’s better than a broomstick!” Four years later, several boys experienced unwanted nighttime visits from seniors trying to fondle them. After Charlie Henry awoke one night during his third-form year, in 1982, to find a darkness-obscured figure touching him, he slept with a knife under his pillow for the remainder of the semester. The same year, some seniors took a freshman boy to a dorm basement, where they beat him up and raped him with a pencil. After the victim went to the administration, Tony Zane announced at Thursday chapel what had happened, and the seniors were expelled. “When their feet were held to the fire, they responded,” says Ned Truslow, who was the school’s senior prefect when he graduated, in 1986, but “how could these people have let this happen?” Franklin Coleman was big and tall, deep-voiced and pompous and kind and charismatic, a rare African-American teacher in a sea of whiteness, and the school’s musical leader starting in 1980: organist, teacher of music theory and history, choirmaster at a school with a singing group serious enough to record albums and tour internationally. He often wore his choir robes around campus. A cult of personality surrounded him, and he played host to concentric rings of acolytes. The Kulture Vultures was a club of aesthetes who’d meet in Coleman’s apartment in the Arden-Diman dorm, which he supervised, to drink soda, eat chips, and listen to classical music or jazz or watch a Hitchcock or Woody Allen film. A more exclusive group, the Colemanites, would receive floridly inscribed invitations to small soirées at Coleman’s apartment; the boys wore black-tie. And then, at the center of these rings, according to alumni, was the small group of students in whom he had a sexual interest. Coleman had a clear type: “that Brideshead, beautiful chiseled young boy” look, as a female ex-choir member describes it, and a predator’s nose for wounded animals. Hawkins Cramer (class of ‘85) fit the profile, blond with a good voice, and his father had died of cancer the summer after his sophomore year. “I was devastated from that, and lost and sad and angry,” Cramer recalls. “Franklin came in as the caring, avuncular guy that he is.” Coleman could be generous, giving him a double tape deck, say, or a Christmas sweater from Barneys, but there was a push-pull. If Cramer’s thank-you note was insufficiently long, he says, Coleman would become petulant and berate him, then apologize and pull him in for “a long embrace. Over time, he’d start pulling up my shirt, putting his hand under it, against my back. It became really uncomfortable, but you’re already in this position where you just had to make this guy feel better—if I pull away now it will make it worse. So you carried on and tried not to think about it much.” Coleman took Cramer on a college tour the summer after his junior year, and the situation became increasingly fraught, with Coleman booking hotel rooms with a single bed and Cramer waking up with Coleman’s arm around him. During a drive on that trip, Cramer fell asleep in the front seat and says he woke up with Coleman “massaging my genitals.” Cramer froze, pretended he was stirring from sleep, and Coleman stopped touching him. Then Cramer opened his eyes and said, “ ‘I don’t know what I’ve done to make you think I want that, but I don’t. You can’t do that sort of thing to me.’ He pulled over, starts bawling and crying. ‘I’m so sorry, you seemed so tense—I thought this would be something to relax you.’ ” Another alumnus told me he was given marijuana and vodka by Coleman, and woke up naked in a bed in Coleman’s apartment with no memory of what had happened. A third alumnus, “Ethan” (who has asked that his real name not be used), who is now in his 40s, was a Colemanite, blond and bullied and far from his home in the Bahamas when Coleman cultivated him, serving him Kahlúa ice cream and writing love notes. Over time, Ethan says, Coleman showed him gay porn videos, gave him a full-body Vaseline massage, and touched his penis. On Friday, May 6, 1988, Ethan told the school counselor, and the counselor told the headmaster, Zane’s successor, the Reverend George Andrews, who fired Coleman the same day. At least half a dozen alumni have reported that they were targets of some sort of advance or contact by Coleman. Even more than Gibbs, it’s hard for many alumni to understand how Coleman was allowed to prey on students for as long as he did. Coleman’s practice of sending invitations to handpicked favorites and posting them on a bulletin board for all to see, which today might be recognized as the grooming tactics of a predator, seemed troublingly exclusionary to some students but were evidently considered acceptable by the administration. A 1986 yearbook photo of Coleman was captioned “Frankie Say Relax,” and there was bathroom-stall graffiti about “Franklin’s organ” and someone sitting on “Franklin’s Tower” (playing off the Grateful Dead song). “We all knew he was a perv,” says one ‘86 graduate. Decades later, the St. George’s counselor would tell the school’s investigator that in the early 80s he had informed Tony Zane about a student’s supposedly receiving backrubs from Coleman, and Zane had responded that he didn’t believe the student and hoped the matter would “go away.” Zane himself told the investigator that he didn’t remember this, but he had warned Coleman around 1983 or 1984 “not to give back rubs to any more students.” Innuendo and the fuzzy conflation of homosexuality and pedophilia in the mind of a 1980s teenager wasn’t actionable knowledge of a specific incident or relationship. “There was a way in which the genteel homophobia of the school organized itself around Franklin Coleman, in a way that weirdly enabled his predatory behavior,” Bryce Traister says, because it made Coleman’s acolytes defensive around him and “also because it suggested it wouldn’t be right to inquire too closely into what was really going on in these years . . . because that would suggest you were being homophobic or racist.” A female member of the class of 1987 says she went to her adviser that year and reported that something untoward was clearly going on between Coleman and some students, and “someone needs to do something.” The alumna says her adviser told her that unless she had evidence “you’re in the same position I am. I said the same thing to the people in charge, and I was told to mind my own business.” When Andrews fired Coleman the following spring, he handled the matter much as Zane had handled Gibbs. The departure was presented as a “voluntary resignation” due to health reasons; the school, on the advice of counsel, made no report to authorities; and the school gave Coleman $10,000 and let him keep his health insurance for several more months, in return for not pursuing any legal claim against the school. Coleman moved on to working with school choirs at a church in Philadelphia, and by 1997 he was choirmaster at Tampa Prep, in Florida. The year that Coleman was fired, 1988, a plaintiff using the pseudonym Jane Doe filed suit in November against St. George’s School in federal court in Providence, alleging she had been raped by Al Gibbs. The plaintiff was Anne Scott, who had suffered in the eight years since she graduated from St. George’s. She had finally started to talk about Gibbs with her therapist when she was a college junior, eventually informing her parents what she’d gone through. But while she had excelled academically, obtaining both an undergraduate degree and a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania, and later an M.B.A., she had been hobbled socially. She had spent much of her 20s living with her parents in Delaware, been hospitalized four or five times for an eating disorder, depression, and dissociation, and was on a number of psychiatric medications. As she entered her late 20s, and her Ph.D. neared completion, her parents were worried: about her marital prospects, her financial prospects (she was aging out of their health insurance), her future. They began to explore the idea of a civil suit against the school. “My parents aren’t litigious people,” Scott says, “but it was that motivation of, how do we provide for Anne, and what’s going to happen when we’re not around and she’s not going to be able to live independently.” Her family retained Eric MacLeish, whom another lawyer had recommended and who, as it happened, had attended St. George’s for two years in the late 60s. St. George’s response to the lawsuit, which sought $10 million in punitive damages, was remarkably aggressive. Although the school was well aware of Gibbs’s history of abuse, then headmaster Archer Harman (now deceased) wrote a letter that December to “Friends of St. George’s,” in which he stated that “we have no reason to believe that the alleged incidents took place.” Besides trying unsuccessfully to have the suit thrown out on the grounds that the statute of limitations for a personal-injury suit had expired, lawyer William Robinson III, who now sits on Rhode Island’s Supreme Court, argued for making Anne Scott’s name public, suggested the sex might have been consensual (a suggestion that earned a withering rebuke from the judge), and tried to stop Scott from notifying other alumni. “They threatened to depose my parents’ whole community,” Scott says. (Robinson said in a statement in January, “I represented the client as an attorney must, zealously, ethically and to the best of my ability.”) The situation produced tension in her family, and ultimately the pressure became too much for her to bear: “I just wanted it to go away. I didn’t want money. I didn’t want to lose my family. I dropped the case.” St. George’s refused to let her withdraw, however, until she signed a confidentiality agreement preventing her from ever discussing the case. MacLeish argued against signing it, but Scott was done. “I basically fled.” She stopped therapy, “cut off everything,” and moved overseas. The school did, in response to the suit, finally stop providing Gibbs with financial support and report him to the Department of Children, Youth & Families (which responded that it had no jurisdiction). The CrusaderOver the next 20 years, America’s understanding of childhood sexual abuse within institutions would evolve dramatically. Eric MacLeish was part of that movement. Anne Scott’s case had been his first in the sexual-abuse area and had launched him on a career: he represented most of the victims in one of the first successful cases against the Catholic Church, in Fall River, Massachusetts, in 1992. MacLeish would become a key figure representing victims in the Archdiocese of Boston cases (in the movie Spotlight, he is portrayed, somewhat unflatteringly, by Billy Crudup). That work would take its toll: MacLeish experienced severe PTSD following the Catholic Church cases and gave up the law, lost 40 pounds, moved into a trailer in his in-laws’ yard in Connecticut, remembered his own sexual abuse at an English boarding school he attended as a child (he also still has cane marks on his back from his time there), and began a romantic relationship with his psychotherapist. (His marriage ended, and he ended up filing a complaint against the therapist with the state, which revoked her license.) As the Catholic Church scandal unfolded, a growing number of other cloistered institutions, including the American Boychoir School, in Princeton, and Groton, in Massachusetts, had to reckon with sex-abuse scandals. And a few St. George’s alumni, still haunted by their experiences at the school, began to seek answers. Ethan, after graduating in 1989, had wandered the world for 12 years as a sailor and “let strange men do things with me.” He had become an alcoholic and extinguished a series of cigarettes on his own body, and he hadn’t come to terms with what had happened to him at the school. (He is now married and living with his wife and son in Westport, Connecticut.) He approached the school in 2000. “I said, ‘I’m not trying to sue, but I don’t know why I have to pay for my therapy.’ ” He says he received a letter of apology, from then headmaster Charles Hamblet, and 23 sessions with the school counselor. Two years later, Harry Groome, reading about an abuse scandal at Groton, and newly the father of a son, was beginning to recognize the psychological impact of what had happened to him and found himself worrying about current students at S.G.S. and what was being done for them. He wrote to Hamblet and says he received a pat-on-the-head letter in response. (Hamblet died in 2010.) The hiring of Eric Peterson as headmaster in 2004 prompted a new set of contacts by alumni. That year, Groome e-mailed Peterson and also the fellow graduate who had assaulted him. Twice a year, he’d see the perp’s name in school mailings, because the man was an active alumnus, and he wrote him: “I said, ‘I never forgot what you did to me; I see your name twice a year; in good faith please resign from that position.’ He wrote back and said, ‘I resigned—let’s please talk.’ I said no.” Hawkins Cramer now had a family and was the principal of an elementary school in Seattle, where he had recently dealt decisively with a teacher exhibiting grooming behaviors with students. Emboldened by that experience, in the spring of 2004, Cramer decided to track Franklin Coleman down. He found him working at Tampa Prep and called him directly. Cramer’s palms were sweaty, his heart thumping. Reception put him through, and Coleman picked up after two rings. “At first he was ‘Great to hear from you,’ ” says Cramer. “I said, ‘I’m not calling because I’m interested in talking with you but to let you know that what you did with me was a terrible thing and you have no right to be around kids.” Cramer told Coleman he was going to get him fired, then called the headmaster, told him everything, and suggested he call St. George’s to confirm the information. Cramer says the headmaster thanked him and said he’d take it from there. Then Cramer called Peterson at St. George’s and told him the story. “He said, Oh my God, that’s terrible, that’s awful, thank you so much.” Cramer says he told Peterson he needed to call the Tampa school. “I hang up, think, That’s great, I’ve done all I can do. Well, [Coleman] retired four years later from that job. So [Peterson] knowingly protected this guy who was a pedophile.” “Mr. Peterson’s recollection is different,” says Joe Baerlein, a spokesman for the school, in an e-mail. “During their conversation, Mr. Cramer said that he should expect a call from Tampa Prep and requested that he speak to them about Coleman. Mr. Peterson agreed to do so but did not hear from Tampa Prep.” (Coleman now lives in Newark, New Jersey, and until recently had a page on Couchsurfing.com, a site where homeowners can offer free lodging to travelers, featuring pictures of himself surrounded by adolescent boys. He didn’t respond to an interview request and has not responded to allegations in other news reports.) In 2006, Ethan met with Peterson on campus, and Peterson, like his predecessor, wrote him a letter of apology and also promised 10 free psychotherapy consultations. In October of 2011, Harry Groome e-mailed Peterson a Boston Globe article about a scandal at the Fessenden School, in Newton, Massachusetts, heading the e-mail: “FYI—how another school is addressing past sexual abuse on campus. Time for SG to step up?” Peterson invited Groome to meet with him, and Groome gave Peterson a copy of the letter he’d sent to Hamblet in 2002. In the spring of 2012, Eric MacLeish wrote to Peterson. MacLeish had found himself reading St. George’s Bulletin and seeing story after story about “successful alums,” he says. “The hypocrisy of it all was just overwhelming.” MacLeish had always been haunted by the Anne Scott case. Over the years, he had tried to track her down, at one point even hiring skip tracers (akin to bounty hunters), without success. Thinking about Anne Scott and all the victims of Al Gibbs, MacLeish wondered, “Why can’t there be an article about that conduct in the Bulletin?” He wrote Peterson that night, asking him to send out an alumni letter about Gibbs. MacLeish had eased back into mediation work after his time in the wilderness, but he wasn’t representing a client then. Peterson invited him to come to the school, and they met and spoke. Afterward, MacLeish wrote to Peterson that the school had “an affirmative duty to act,” but Peterson still didn’t send out a letter to alumni. In 2014, MacLeish was at a Christmas party in Lincoln, Massachusetts, where a fellow lawyer said he was in touch with someone MacLeish knew: Anne Scott. In the years after she left the country, Scott had ended up doing global health and development work for NGOs in Indonesia, India, Botswana, and the Palestinian territories, among other places. She found it healing to see people in impoverished countries showing grace, and being an expat had removed her from the painful context of her own culture, freeing her to be herself. In 2013, with her two sons, now teenagers (the marriage that produced them hadn’t lasted: “holding on to friendships and intimate relationships is hard for me”), she decided to move back to the U.S. after a quarter-century abroad. MacLeish called her that December, and when Scott received the phone message, she thought long and hard about calling him back. When she did, he brought her up to date—about how he’d reached out to Peterson in 2012, and how her case and its resolution had always bothered him—and asked her to speak to the school with him. She said that if it would help others and make the school a better place, she’d do it. What happened next set the tone for everything that would follow. MacLeish, who in the past year has gotten back to doing trial work, asked Peterson to lift Anne Scott’s gag order, and arranged for the three to meet. MacLeish also then sent, unsolicited, a draft letter for Peterson to send to alumni. It was an aggressive move, and at that point Peterson, a lawyer, said he wasn’t so sure a meeting was such a good idea. Two weeks later, Peterson and then board chair Skip Branin sent a letter to all alumni, announcing that the school had become aware of past “sexual misconduct” by at least one employee, had hired an investigator to undertake “a full and independent inquiry,” and encouraged any alumni who had been victims or had pertinent information to speak with the investigator. Peterson wrote that the letter and inquiry had their roots in another alumna’s contacting him in 2012 about her Gibbs abuse experience, in the evolving best practices of independent schools, and in response to “other alumni” coming forward. (MacLeish believes that he forced Peterson’s hand.) In May of 2015, MacLeish, Anne Scott, Peterson, and a lawyer for the school met at MacLeish’s office. Scott told Peterson her story and made several requests: the creation of a therapy-assistance fund, a release from her 1989 gag order, documents from her lawsuit (to help in her healing), and the removal of Tony Zane’s name from the girls’ dormitory. (Deerfield had agreed to a similar request, removing the names of two offending former teachers from a squash facility, an endowed chair, and a writing fellowship.) “Eric Peterson did apologize and acknowledge that it happened to me, and that was meaningful, and I’m grateful someone acknowledged it after all these years,” Scott says. For a period, Scott felt good about the process. Then things started to go awry. A Fatal CourseThe details—how therapy reimbursement would work; whether or not survivors would have to sign confidentiality agreements; whether the school would release Anne Scott from her 1989 gag order; when exactly the investigative report would be finished—are less important than that, by the fall of last year, an adversarial dynamic had been established: Anne Scott, and a growing group of other alumni who’d stepped forward with stories of their own abuse, began to feel that the school was responding to profound pain with lawyerly caution and was more interested in protecting its reputation than truly making amends and ensuring that the problem had been addressed. Even as the school proceeded with its investigation and sent two more letters to alumni updating them on its progress, the survivor group became increasingly mistrustful, and they learned—only in December, MacLeish claims—that the investigator was a law partner of the school’s outside counsel (as well as married to her). It’s not uncommon for independent investigations to be conducted by an organization’s outside counsel, but in light of the survivors’ obvious trust issues, it’s understandable that when they learned of the law firm’s dual role, they felt betrayed once more. The survivors’ pivot from focusing on past misconduct to what they saw as present mishandling of the crisis would be hugely consequential in prolonging the scandal. Those who blame the school see a culture of cover-up and credit MacLeish with goading St. George’s to act when it otherwise wouldn’t have. Defenders of the school, even while acknowledging some missteps, say MacLeish riled up the victims, driven by his own demons. “I really think this is part of a personal-rehabilitation campaign for him,” argues one former St. George’s student. MacLeish ramped up the pressure on the school. He is adept at working the media, and on December 14, The Boston Globe ran a front-page story about Al Gibbs’s victims. On December 23, the school released its investigative report, but the survivors considered it woefully inadequate: among other flaws, it curiously didn’t address any allegations after 2004, the year Peterson arrived, and it didn’t delve into how the school had “passed the trash” (as the practice of letting a known abuser move on to another institution without alerting them is charmingly called). On January 5, in Boston, MacLeish held a lengthy press conference with Scott and two other victims, and also issued a 36-page rebuttal of the school’s report. The school had lost any control. An online petition by a Scott-led group called SGS for Healing, asking for a new, truly independent investigation and an independent therapy fund administered by a clinician, got nearly 850 signers. And the pressure yielded results. The school announced a new investigator and a therapy program that the survivors were happy with. Meanwhile, a secret group on Facebook, open only to St. George’s alumni, quickly collected more than 1,000 members, as students from the 1960s through 2016 hashed out the scandal. There were first-person accounts of abuse, expressions of solidarity with the victims, confessions of survivor guilt. The class of 1974 rescinded its yearbook dedication to Al Gibbs. There was considerable focus on the culpability of Tony Zane. (In a December 24 e-mail to friends, he and his wife, Eusie, defended themselves and bitterly attacked Peterson for, among other things, refusing to indemnify them and negotiating with MacLeish: “St. George’s School has embarked on a fatal course, has embraced a viper, and thrown us under the bus.” He told the school’s investigator, according to the report received by the board, that he “wanted to make amends and help the students.” Notwithstanding that, he sent another e-mail to friends, in which he wrote, “Anne Scott did not contract anorexia at St. George’s; she arrived severely anorexic.” Scott then wrote to him. “I said, ‘Please stop. It’s not true.’ He didn’t reply . . . . All the guy has to do is say he’s sorry. ‘I’m sorry it happened while I was there’ would be a good start.”) The Facebook group got ugly, too. Some people were expelled from it; others, burned out, quit. People posted scurrilous rumors about family members of St. George’s administration. Sometimes, when things really got heated, people tried to re-inject some perspective and recall some of the good things about their St. George’s experiences. Jason Whitney (class of ‘90) found himself driving home listening to Led Zeppelin’s “The Rain Song” and being transported back to the first night he’d heard it, which was at St. George’s. He posted to the Facebook group: “Put the regrets away for a few hours. Now go cue up the Zep. Do it. Oh, and turn it way the fuck up too. Remember how epic St. George’s could be.” The post sparked more than 100 nostalgic comments. As the second investigation proceeded, the survivors pressed a case against Peterson. Beyond what they viewed as his unresponsiveness to their early attempts to alert him, they were increasingly bothered by the absence of post-2004 allegations in the report released by the school, given that they knew of at least one that the investigator had been informed about. It was a matter involving a computer-science teacher and athletic trainer named Charles Thompson. In 2004, 18 students had made allegations that he’d touched their knees (he had a preoccupation with “sailor’s knees”) and pulled back a shower curtain in one case. It was “creepy,” an administrator would tell the school’s investigator, and parents of the boys in the dormitory received a letter from Peterson explaining the situation. Thompson was removed as a dorm master, suspended for several months, and given a psychiatric evaluation before being allowed to return. He later moved to the Taft School, in northwestern Connecticut, but after the St. George’s survivor group alerted The Boston Globe, it ran an article about Thompson, and he was placed on leave by Taft. (Thompson remains on leave and did not respond to a request for an interview. Some St. George’s alumni have suggested that the evidence against him is weak and that he’s the victim of a witch hunt.) During all this, the school hunkered down, giving no interviews after the initial Globe story and hiring both the same law and crisis P.R. firms (Ropes & Gray and Rasky Baerlein) that had represented the Archdiocese of Boston. But a group of alumni and current parents defended the school on Facebook and in interviews. One of their main arguments, always couched with expressions of sympathy for the survivors, is that nonetheless St. George’s is a “living school,” and that present-day students and parents and faculty shouldn’t be punished for the sins of the past. A current student assembled a spreadsheet showing how far the school had come in terms of gender equity, charting how many girls are now in leadership positions and how many female faculty there are. And in the void of Peterson’s public silence, some alumni and parents have stepped up to defend him. They point to the money he’s raised and the programs he’s championed, which have made the school a more academic place, as well as to his popularity among students and their parents and to his moral authority: there was, for instance, the decision a few years ago to forfeit a football game against rival Lawrence Academy, because Lawrence’s team was stocked with 300-pounders. While this briefly turned St. George’s into sports-radio fodder about the softening of the American male, others saw it as an act of courage. At a meeting in Newport in February, St. George’s parents roundly expressed support for Peterson. Tucker Carlson, the conservative commentator, graduated in 1987, married headmaster Andrews’s daughter Susie (who now sits on the board) and has sent two of his children to the school: he thinks it’s “disgusting” how people have gone after Peterson, who he believes has been unfairly scapegoated for things that happened long before he was there. Governor Howard Dean, the former presidential candidate and a 1966 graduate of St. George’s, also supports the current leadership. “I was outraged when I first read about [the abuse],” he says. “I hate this kind of stuff. But the more I learned . . . what matters to me, classically institutions sweep these things under the rug, but in this case, I don’t detect stonewalling . . . . My guess is they’re trying to do the best they can by the victims. I don’t see any evidence of this administration or this board, none of whom I know personally, that they’re trying to shut it down. I don’t know what else we can ask of them.” Even Whit Sheppard, whose experience at Deerfield is cited by MacLeish as an exemplary response by a school to a case of abuse, says, “I firmly believe that Eric is a person who’s genuinely interested in doing the right thing by survivors, for survivors.” Regarding the outward paralysis of the board of trustees, a current member of the school’s advisory board offers a benign explanation: “No one’s going into these conversations saying, O.K., tell me how to stonewall. They’re saying, What do we do in a P.R. world where anything we say gets heavily criticized? How do we come across as ready, willing, and able to deal with issues raised without setting ourselves up for automatic failure or liability in the future? Those are tough things to navigate. And lawsuits are coming. No matter how well intentioned you are, you have to keep that in mind.” That still doesn’t explain, though, why Peterson didn’t send out an alumni letter before 2015, or why it took him seven months to release Anne Scott from her decades-old gag order. It’s hard to avoid the sense that he either was dragging his feet and acting only when forced to, or was at the mercy of a board that wouldn’t let him act. It’s also hard to avoid the sense that the board did a bit of sanitizing of the first investigative report, a copy of which was obtained by Vanity Fair. The report publicly issued by the board was 11 pages, but the original pair of reports (a main one and a supplemental one) received by the board exceeded 100 pages. A reasonable case can be made for much of the winnowing that was done: a teacher who was a bit inappropriate, and was disciplined and investigated and ultimately cleared to work at the school again, arguably did not warrant inclusion in a report about sexual abuse. Other details that were excluded, like the facts that a former St. George’s teacher is currently in federal prison for possession of child pornography and that another one told a male student that “you just need a good fuck,” look more like a school sparing itself some embarrassment. It’s unclear why the board didn’t consider it important to disclose the investigator’s finding that “the perception among many former members of the school community is that [a culture of abuse] did in fact exist decades ago at the school.” More disturbingly, the published report excluded the investigator’s finding that the school had given Al Gibbs a letter of recommendation and a stipend after firing him; had lied about having no reason to believe Jane Doe’s claims were true; and had never attempted to alert White’s, Gibbs’s, or Coleman’s later employers about their pasts. “Why Would They Get It Right?”I visited St. George’s on a Monday in early May, a week before the reunion weekend. It was a misty, overcast morning, but the handsomeness of the campus, with its abundant green lawns and looming stone chapel, all backed by the rolling surf of the ocean, was inescapable. First period was just beginning when I arrived at 8:30 A.M., and boys and girls and teachers were hurrying to their classrooms. The school is larger now—50 percent more students than in the 1980s—with a new science building, a new library, a new arts center, and a state-of-the-art facility for the professional development of faculty. At an assembly I attended, run by the five senior prefects, the athletic director handed out awards for athlete of the week; a student group announced a project involving “design thinking,” a concept Peterson had brought back from a continuing-education program at Stanford; and another club announced that Julie Bowen (class of ‘87), who plays a mother on Modern Family, would be speaking on campus the following week. Then I sat down with Peterson in his office, a high-ceilinged space with wood paneling that is exactly as you imagine it. Peterson—a young 50, square-jawed, clean-shaven, earnest—wore a black St. George’s fleece vest over a shirt and red tie. He had invited me to the school so that I could see St. George’s as it is in 2016, but also said that he was constrained from speaking about its history of abuse. It was an odd set of circumstances that neatly encapsulated the situation Peterson finds himself in. Managing the greatest crisis ever to hit St. George’s, and concerning events that mostly took place long before he’d set foot on the campus, he has had to simultaneously answer to trustees, to current students and parents, to faculty, to alumni, to survivors, to donors, all while a Rhode Island state-police investigation was ongoing (it has recently concluded with no charges being brought), the school’s own second independent investigation was pending, and plaintiffs’ lawyers were circling. Peterson also has a school to run. (And he’s well paid to do so: $525,000 in 2014.) A strategic P.R. adviser sat between us. We touched on the school’s current anti-abuse precautions, on the wave of prep-school scandals, on the greater contemporary sensitivity to adolescent development. Peterson spoke of his pride in the school’s more robust honor code (adopted nine years ago), in recent changes to student life (“We’ve established somewhere in the neighborhood of 40 new student traditions”), in the tone he’s tried to foster. “I say to the students all the time, ‘We don’t do mean. Mean is a choice.’ ” I asked him about his decision to leave the law for teaching. “My heart was a teacher’s heart,” Peterson said. He talked about the continuing purpose of boarding schools. Peterson, who grew up in Laguna Beach, California, was the first person in his family to go to a private school, and his years at Deerfield had been “transformative. I didn’t know what school could be until I went to boarding school.” While the survivors I’d talked to, and their allies, seemed mostly adamant that Peterson must go, there had recently been glimmers of détente—at least with the board. Just days after the uproar over the misbegotten “Hope for Healing” event, five survivors met with five trustees and a mediator in Boston. The trustees had agreed that the board would undergo training on the long-term impact of child sexual abuse and would also discuss “reparations” for survivors. The five trustees also agreed to consider survivors’ criticism of Peterson and act on any issues raised about him by the report within 30 days of its release. The report was expected to be published in June, but its likely impact was pre-empted when, early that month, board chair Leslie Heaney announced in a letter to the school community that Peterson had recently told the board he would not seek to extend his contract beyond its end date in June 2017. The news did not appease survivors, who were disappointed that Peterson hadn’t been explicitly fired, that he would keep his job for another year, and that his own letter to the school community alluded only obliquely to the scandal. Many of the survivors and their allies see what’s happening as an opportunity to help the school become a better place. They say they don’t want to tear St. George’s down but to rebuild it. Anne Scott, who after 25 years of being under a gag order was at first mortified to have the details of her life—her abuse, her hospitalizations, her medication—spilled on the pages of newspapers, has found meaning in this fight. “Our society has to start talking about this stuff,” she says, “and maybe I can play a small part in that by putting my head over the parapet and talking about it and answering people’s questions. A lot of what the school says is not evil, but it’s ignorant and tone-deaf to survivors. But why would you expect them to understand something that’s taboo and nobody gets any practice in talking about or understanding? Why would they get it right?”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.