|

'Like a spider that keeps building its web': family of sexual abuse survivor speaks out

By Melissa Davey

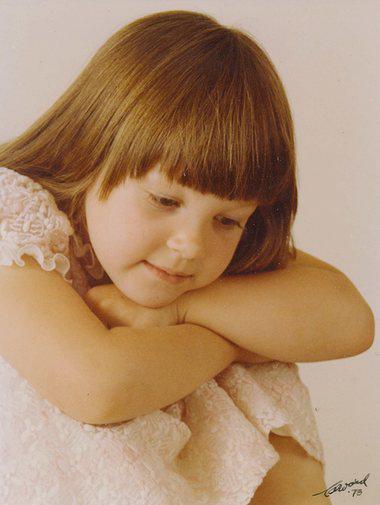

When Meg was 12, her mother, Annie, found herself unable to look at her. Seeing her daughter made Annie feel unsettled, at times almost angry. At first, she couldn’t figure out why. “And then, Meg turned 13 and suddenly, everything slid into place for me,” Annie says. “I found myself thinking, ‘She’s so tiny. She is so little.’ And I realised I was actually talking about myself, not her. “It felt like something just broke. It was something big and ugly, and it just broke.” Annie was 13 in 1987 when an Anglican priest began sexually abusing her, over a period of eight to 10 months. Seeing her daughter turn the same age was a trigger that not only bring back memories of the abuse, but that also helped her to comprehend just how small and innocent she would have been. He was in his mid 30s, and used Annie’s vulnerability after the acrimonious divorce of her parents and his knowledge that she had been sexually abused by a family member to his advantage. Annie’s experience of cover-ups, betrayal and being failed by those who should have protected her has become all too familiar in such cases. But it is the experience of her family members she wants to highlight. They are the secondary victims, whose stories are often lost. Annie and her family believe abuse pervades the lives of secondary victims but support for them is haphazard and scarce. They hope that by sharing their experiences, religious and other institutions will do more to recognise and address the impact of abuse beyond the primary victim. Meg said at first she was unsure why her mother had begun to treat her differently. She did not know the extent of her mother’s abuse at the time. “I guess it was always obvious that something had happened to Mum, because sometimes she would cry or blank out but I didn’t know exactly what she was upset about,” Meg, now 14, says. “But when I first turned 13 that’s kind of when I knew something more was going on. For a while though, I thought I’d just done something wrong, I thought I’d upset Mum in some way and that’s why she couldn’t really talk to me any more.” Robbed of a childhoodAnnie was first raped when the priest lured her alone into the church where he preached. Knowing that Annie was devastated about the death of her dog, the priest told her that if she looked toward the altar and prayed to God, she would see her beloved pet again. He made her lean towards the pew and, as she did, he pulled down her underwear and sexually abused her. Annie’s police statement was made last year, when she was 42. “After I got home there was a lot of blood there and it hurt for a while,” it said. “For around two weeks, I remember I had a lot of trouble going to the toilet.” Annie recalls the priest raping her five times. She is unsure why the abuse eventually stopped. But it she says it robbed her of her childhood and left her without an identity, unable to accept love, her victim impact statement said. By the time she was in year 12, Annie had a nervous breakdown. Her former high marks at school crashed. Her mother threw her out of home for several weeks, forcing Annie to steal food from garbage bins to survive. When her mother accepted her back home, Annie was terrified of starving again, and began to eat as much as she could and to hide food in her bedroom. Between 1991 and 1992, Annie gained 30kg. In 1994 Annie’s mother made her talk about her withdrawn and surly behaviour to a bishop her mother was friends with. Annie brought up the name of her perpetrator to the bishop. He told her: “I’m going to stop you here.” “I want you to think very carefully about coming forward with this,” Annie recalls him telling her. “Think of the lives that could be ruined by this.” The bishop questioned Annie’s memory of what happened and told her that if she told anyone else, people would think she wanted it, that she was partly responsible. Letters written by church officials at the time and seen by Guardian Australia reveal that senior members of the church knew of the priest’s abusing but did nothing. Annie’s mother called her a slut and a whore. She accused her daughter of breaking up the family by causing trouble. Though she was awarded a scholarship to attend a prestigious college in 1994, Annie dropped out after less than a year. That same year, when she was 21, she tried to take her life. She has since worked in low-level jobs where people half her age serve as her boss. She cannot go near churches, even for funerals or weddings. She dreads sleep because of the nightmares she knows will come. She has considered and attempted suicide more than once. Annie’s husband, Mark, and her three children, Robert,Meg,and Ella, do not know the full extent of her abuse, though they know most of the crucial details. As the years go by, they learn more, sometimes accidentally, such as when Annie talks in her sleep. Or sometimes, by necessity, as the calls from detectives and from the church require an explanation. ‘If you hide something like this … it’s wrong’Dr Judy Courtin, a lawyer representing victims of institutional sex abuse at Angela Sdrinis Legal, published research last year into justice outcomes for sexual assault victims abused within the Catholic church. She interviewed 18 secondary victims – defined as immediate family members – and found an admission of guilt by the perpetrator was important to them. “But an even bigger concern I found from them was their anger at the ongoing way the church concealed the crimes, and a need for those people to also be held to account,” Courtin says. “They felt that those who knew about paedophiles and yet kept quiet fundamentally enabled the activities of paedophiles. They protected them, they covered up their crimes, and they were often not held to account, and that’s something that really upsets secondary victims. That maybe their family member wouldn’t have been abused if those who knew had spoken up.” The finding resonates with Annie’s son, Robert. He learned about the abuse of his mother just before Christmas, after he had finished his year 10 exams. Annie and Mark had been talking to detectives and representatives from the Anglican church and they felt it was time Robert knew what was going on. He is angered most by the fact that no one had helped his mother. “It’s almost worse, not helping when you can see something is wrong,” Robert says. “I’m a firm believer that if you see or know about something wrong you have to do something. If you hide something like this happening to someone it’s wrong.” “They [the church] should also know that the effect isn’t just on that one person. “It’s like a web. Like a spider that keeps on building its web, things like this just keep building. I’m not the only one who has been affected, my friends have, too, even if they don’t know it, because they see how I am affected. They don’t know what the cause is, and they won’t for a while. But they see something is wrong.” Robert says he feels angry that he cannot always talk about the problem with friends or adults who “think the world is safe and simple”. “But it’s not. Because sometimes I come home and I’ve got Mum going through this. I’ve got Ella, who doesn’t really know what’s going on, but who is asking questions every day. She’s always confused and always wants to know more. And I’ve got Meg, who is lashing out because of it. And it’s painful at times.” There is no support group, no place to go outside his family, Robert says, for other teenagers like him. He thinks a safe environment for other children of survivors to meet and talk in would help. “It’s something I would like to be involved in,” he says. Annie has looked into it. But she says there are significant gaps in accessing support and even counselling for survivors and their families. Survivors often have to bear substantial costs of private counselling, while civil claims against the church may also be draining their funds. ‘There’s stuff I still don’t know’Annie’s husband, Mark, says he learned about Annie’s abuse shortly after they started dating in 1996, though she wasn’t necessarily upfront about it. He would hear her call out in her sleep, and ask her the next morning about some of the things she had said. Over the years, Annie has gradually told Mark more. Since Annie first told her story to police last year, Mark has learned about the extent her perpetrator went to to harm her. But there were times while giving her statement that Annie would not allow Mark to stay in the room. “I was very stressed by that,” he says. “There were just two cops and a video camera, and she’s telling them things she doesn’t want me to hear. “I’m thinking, ‘These are the points where she’s at her most vulnerable and that’s the moment she really needs someone she trusts and knows loves her to be there with her.’ “And there’s stuff I still don’t know,” Mark says. It took Annie 19 years of Mark gently encouraging her before she went to police in January last year. Mark had to walk a delicate line between supporting Annie in whatever choice she made, while also navigating his own anger towards the perpetrator and the church. She was fearful that if she went to police, Mark would learn the full extent of her abuse, and that knowing the details might prove too much for him to bear. “Mark’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me,” Annie says. “You don’t muck around with that.” He replies: “This is what it’s like to be someone who supports a survivor. “I know what I can’t handle. Of course there are things that will break a human. But this isn’t that. The things that I’m vulnerable to aren’t these things. But despite 20 years of trying, Annie can’t trust me when I say that. “And that’s my struggle. I’ve got to live with the fact that Annie can’t completely trust me the way I’d like her to, the way I trust her. And I just have to accept that. That’s part of the package. She can’t completely trust me. She can’t completely trust anyone. “She’s still convinced that there are things, when I hear about them, that will be it. “That I’ll never be able to look at her again.” Mark says he feels a certain sense of relief now that Annie’s attacker has been charged with 16 offences. He will face court next month. He had been jailed before, in 1996, for child sexual abuse offences unrelated to Annie. “I found it’s easier for me since Annie came forward than it was before, because now it’s out in the open. While I’m not telling everyone I know, I feel I can talk about my feelings about how angry I am with the church and the people who covered this up more safely.” ‘Everything suddenly makes sense’Shireen Gunn is the manager of the Centre Against Sexual Assault in Ballarat, a town that has been deeply affected by child sexual abuse within religious institutions. As well as primary victims, the centre works with the family members of those who were abused. Disclosure often comes as a relief to them, she says. “For many family members of survivors, especially the children of parents who have been abused, everything suddenly makes sense to them once the victim discloses that abuse,” Gunn says. “Suddenly certain aspects of their childhood or behaviours from their parent start to make sense, it helps them to make sense of their experience. “The other response from secondary victims is, of course, anger. They want to do something to hold their family member’s perpetrator to account. But it’s very important that the victim or survivor have control over what happens, and if and when they take action or go to police.” There is little research on the impact of sexual assault on secondary victims, the Australian Institute of Family Studies says. “To the extent that secondary victims are considered in the literature, the focus is usually on the manner in which their response to the victim/survivor’s experiences helps or hinders the primary victim’s recovery,” the institute says. “This is an important concern. Higher levels of unsupportive behaviour by family members has been found to be more likely for sexual assault victims than for victims of non-sexual assaults.” But few studies had examined the trauma experienced by someone finding out a family member had been sexually abused, the institute says. The royal commission into institutional responses into child sexual abuse acknowledges the lack of research. A commission spokeswoman told Guardian Australia a comprehensive research program is under way looking at survivors and their families. But the commission does not yet have statistics about how many secondary victims of abuse survivors there might be.“The research projects under way are exploring a number of questions: what are the impacts of child sexual abuse on families of minors? What are the impacts of child sexual abuse on the intimate partners and children of child sexual abuse survivors? And what are the support needs of the families of child and adult child sexual abuse survivors?” she says. Annie says there is not enough acknowledgement of the quiet role secondary victims play in trying to be supportive while grappling with their anger and sadness. While telling her family about the extent of her abuse has been difficult, especially while also repeating her story to members of the church, the royal commission and police, Annie says the experience has ultimately proved worthwhile. “There is a certain kind of freedom that comes with coming forward,” she says. “The process is flawed, it’s not right, it’s not OK, and survivors and their families deserve better. Supporters need to know the way you say things has the potential to horribly damage a survivor who is already struggling under the weight of coming forward. “But you can also help amplify a silent voice. I am a person coming forward and coming forward means that you are saying you are a person. You’re not a thing. “Nobody has the right to use you. “You’re real. You exist. Your survival means you have the right to peace in your life. “You have the right to be able to look at your own kids.” Contact: melissa.davey@theguardian.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.