|

Archbishop Flores dies

By J. Michael Parker And Elaine Ayala

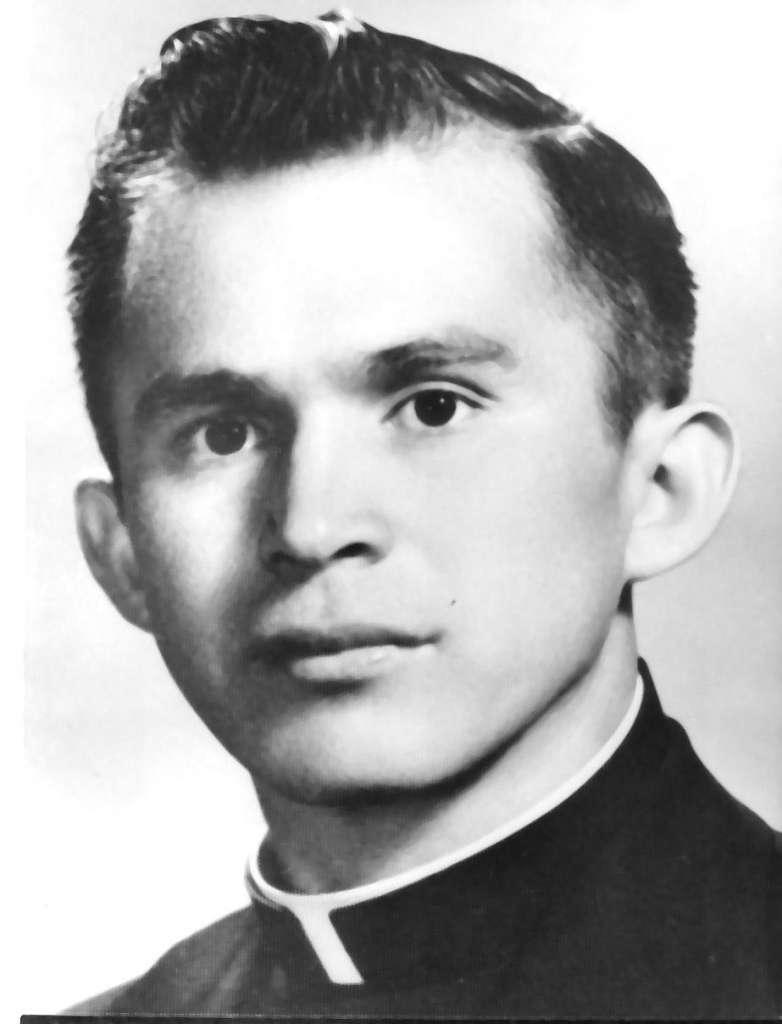

Retired Archbishop Patrick Flores, a onetime migrant farm worker and high school dropout who overcame discrimination to eventually become the nation’s first Mexican-American bishop, died Monday in San Antonio. Flores, whose full name was Patricio Fernandez Flores,waged a long battle with congestive heart failure, dementia and Meniere’s disease, a hearing disorder that causes veritgo, tinnitus and hearing loss. In the end, he suffered pneumonia. He had not been seen in public much since 2008 and was living in Padua Place Residence, a retirement home for priests. The beloved prelate, credited with blazing a path for several generations of U.S.-born Latino priests and bishops to follow, was 87. He was the fourth archbishop of San Antonio, helped found several educational, social justice and charitable organizations and became the de facto leader of the nation’s Hispanic Catholics. Last weekend Flores was hospitalized briefly at Baptist Medical Center but was released, put in hospice care and returned home to Padua. Funeral arrangements are pending, but Archbishop Gustavo García-Siller said Monday that San Fernando Cathedral would be the likely place for Flores services next week, which will include a period of lying in state. García-Siller, whose voice broke several times during a Monday press conference, called Flores’ death “a great loss” for not only the Archdiocese of San Antonio but for the larger Catholic Church. “Archbishop Flores was a man of charity, a man of great endurance and someone who loved people, especially the poor, the neglected (and) the downtrodden,” he said. “We are all so blessed to have known him.” García-Siller said Flores’ lifelong commitment to the poor never faded. “His will was only half a page long,” García-Siller said, listing the few possessions that Flores left, among them a cross, a ring and an ecclesiastical vestment called a pallium. “I owe him a huge debt of gratitude,” said Father David Garcia, who served as Flores’ chief of staff and was later promoted to rector of San Fernando Cathedral. Early in his career, Garcia shared a residence with Flores and was surprised to learn Flores spent his Saturdays visiting the sick, an unusual task for someone at his level. “It was just another way to serve,” Garcia said, noting that Flores didn’t care about the trappings of the office. Garcia remembered the day Flores became an auxiliary bishop, Cinco de Mayo 1970, in the old HemisFair arena. “It was packed to the rafters,” he said. “He was the first. That puts him at more than 46 years a bishop, which is extremely rare.” Flores was appointed bishop amid the Chicano Movement and spoke out against discrimination and was a friend of United Farm Workers co-founder César Chávez. He served as bishop of the Diocese of El Paso for a short time in the late 1970s. In 1979, Flores became the first U.S. archbishop appointed by Pope St. John Paul II and was the last to retire before John Paul’s death in 2005. When he stepped down Feb. 15, 2005, after 25 years and four months, Flores was the nation’s longest-serving archbishop. Early history Born July 26, 1929, in Ganado, a small town northeast of Victoria, Flores learned firsthand what it means to be denied service because of skin color and to be excluded from segregated facilities — both white and black. As a child, he experienced the sting of racism and the anxiety of languishing in a jail cell without assistance. At 12, Flores walked two miles to school — a decrepit one-room building with “crumbling benches, no blackboard, no indoor plumbing and only a single wood stove for heat,” as he recalled years later. On the way, he had to pass a spacious, modern school with many classrooms for Anglo students. Flores often said his parents had provided “a seminary in the home,” instilling deep religious devotion in their children. Siblings recalled how the young Flores always wanted to become a priest, even teaching catechism classes to area children as a youth. He said when he broke the news to his girlfriend that he was going to become a priest, they were 10 miles from his home. She indignantly drove away without him, leaving the future archbishop to walk home in the middle of the night. Initially discouraged by Anglo priests who didn’t think he could meet the academic standards of the seminary, Flores went on to become a priest, ordained in Houston on May 26, 1956. He turned down an offer to study in Rome — a sign of hierarchical favor — and was told he’d thrown away his only chance to become a bishop. He simply shrugged and said that was not his ambition; he’d only wanted to be a parish priest. An associate pastor and later pastor at several Houston parishes for 14 years, Flores became active in the National Association of Hispanic Priests, which lobbied the U.S. Catholic bishops’ conference to recommend the appointment of Hispanics as bishops. But he said he was caught completely off guard in early 1970 when Archbishop Raimondi told him that San Antonio’s Archbishop Furey wanted him — and only him — as auxiliary bishop. Required to submit three names to Rome, Furey simply wrote “Patrick Fernandez Flores” three times. Rome quickly got the message. The mariachi bishop Known for his enthusiasm, Flores exuded energy and was dubbed the “mariachi bishop” for his singing voice and his affinity for breaking into song with the first strings of a mariachi’s violin. A 1987 biography of Flores by Marianist Brother Martin McMurtrey said Flores was never merely respected because of his office but more deeply admired and loved because of his warmth, charisma and spontaneity. Within a month of becoming a bishop, he startled and delighted residents in a public housing project by singing and dancing with them. “Nobody had ever seen a priest do that before, much less a bishop,” Garcia recalled. A successful and frequent fund-raiser for numerous charitable causes, Flores often convulsed audiences with laughter by telling a story from his early days as a priest in Houston. He said a small child had a quarter lodged in his throat, the mother was frantic and someone said, “Call Father Flores. He can get money out of anybody.” He was at ease with presidents and people in power, but his ascent only seemed to deepen his emotional bond with the poor and the voiceless. A nationally renowned role model for young Latinos in his day, Flores founded the National Hispanic Scholarship Fund, which has granted millions in scholarships to Catholic and non-Catholic students. He also founded Communities Organized for Public Service, now known as COPS/Metro Alliance, which organized people in poor neighborhoods and taught them to lobby public officials and hold them accountable. Flores was co-founder of the Mexican-American Cultural Center, now known as the Mexican American Catholic College, which provides Hispanic-oriented pastoral education. He faced controversy and criticism from his first days as an auxiliary bishop when some Anglo Catholics resented his close identification with Mexican-Americans and the poor. On the very day of his installation as archbishop in October 1979, his candid answer to a reporter’s question about a public housing controversy — “If you reject the poor, you reject Jesus” — fueled criticism. Six months later, he got more criticism for a letter to the San Antonio City Council, in which he criticized the appointment of an Anglo police chief over a Hispanic candidate he believed was better qualified. He always said his deepest sorrow was over sexual abuse by priests. He insisted he’d acted in good faith and, with one early exception, always removed abusive priests from ministry immediately upon learning of credible allegations. Others angrily disputed his claims, saying he didn’t believe their allegations and demanded proof. A saint visits The pinnacle of his career came in Sept. 13, 1987, when he hosted Pope St. John Paul II, the first pope to visit Texas. One million people saw the pontiff, including 350,000 at an outdoor Mass in San Antonio. The archdiocese said Monday that event still holds the record for the largest gathering in the state. Flores had invited the pope to San Antonio in 1985, and early in 1986, the enormous and complex task of organizing, preparing for and financing the event began. After the Mass, he rode with his distinguished guest through 22 miles of admiring crowds in the popemobile. The pope slept in Flores’ Assumption Seminary apartment that night before flying to Phoenix the next morning. Flores didn’t spare the Polish-born pontiff a few jokes about the kind of foods prepared here for the visit: “Tacos Polaccos” and “Tortillas con papa.” “Polacco” is the Spanish word for a native of Poland. “Papa” is a pun - “el Papa means “father” or “the pope,” while “la papa” means “potato.” Admirers hoped Flores would be made a cardinal. But that didn’t happen, and he insisted he didn’t want the honor. He said it would require too many trips to Rome and being archbishop of San Antonio was honor enough. Flores was put in danger several times. In 1976, he was among more than 50 U.S. and Latin American bishops held hostage by the Ecuadoran secret police for 28 hours. The bishops were meeting in Riobamba, Ecuador, 130 miles south of Quito, when the police burst in, forced them to board buses and took them to a military camp near Quito. All were eventually released unharmed. On June 28, 2000, a man with a hand grenade, identified as Nelson Escolero, held Flores hostage for nine hours in the archbishop’s third-floor chancery office. The grenade proved to be a dud. Throughout his long career, Flores never forgot his roots and was constantly finding ways to help people in need. He founded Telton Navideño in 1976 to raise money for poor, elderly San Antonians who needed help with food, rent and medicine. He also launched an annual breakfast to raise funds for the Battered Women’s Shelter with himself as chief cook and celebrities from all the community as waiters. He also collected guitars for at-risk youth, arranging for music lessons. To the very end, his door remained open.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.