The Rise, Then Shame, of Baylor Nation

By Marc Tracy And Dan Barry

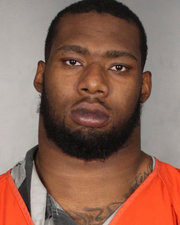

With spring in the Texas air, some Baylor University students were navigating the social challenges of another off-campus party, chatting and dancing while trying not to spill their drinks. Amid the swirl, a petite freshman named Jasmin Hernandez lost sight of her friends. Then Tevin Elliott, a 20-year-old Baylor football player dating someone she knew, appeared. Earlier he had been pouring hard liquor for Ms. Hernandez and other underage students; now he was insisting that her friends had gone outside. When Ms. Hernandez expressed doubts, she said, he began pulling her by the wrist toward the door, telling her they had gone outside. But the farther they strayed into the darkness, the more she argued that her friends were back at the party, and that they should return. Without a word, she later said in a lawsuit, the 6-foot-3, 250-pound linebacker picked up the 5-3 freshman and made his violent intentions clear. Panicking, Ms. Hernandez told him that she was sorry if she gave him the wrong impression; that they should just go back to the house and forget this ever happened; that she was, in fact, gay. He acted as though he did not hear. When Mr. Elliott finished raping her behind a secluded shed, an angry Ms. Hernandez used an expletive in demanding her shirt back. “He tossed it over to me,” she later recalled. “And that was the end of the interaction.” Ms. Hernandez, who has appeared on ESPN and who spoke to The Times for this article, assumed that her rape was a horrible but isolated incident at Baylor, a private university of nearly 17,000 students that takes pride in its Baptist foundation. And she wasn’t alone in believing that: Even after Mr. Elliott was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in 2014, Baylor officials said they considered him to be a solitary bad actor preying on a campus of goodness.

As three leading members of Baylor’s Board of Regents later described their sense of him at the time: “an isolated case.” Mr. Elliott has subsequently been accused of sexually assaulting several other women, and since the rape of Ms. Hernandez in 2012 the allegations of sexual assault by Baylor football players have multiplied, causing incalculable damage to the university’s reputation and leading to resignations and firings, including those of the president, the football coach and the athletic director. The crisis has left alumni apoplectic, students outraged, donors turning on one another, and the Board of Regents bracing for the next blow. Lawsuits clutter the courts, with more than a dozen women, including Ms. Hernandez, claiming that they had been assaulted amid a campus culture that put them at risk. Two months ago, John Clune, a Colorado lawyer who specializes in cases of campus assault and who had already resolved three other women’s claims against Baylor, filed a lawsuit on behalf of an alleged victim that sought, in part, to quantify the crisis. It made the startling claim that at least 52 rapes by at least 31 players had occurred from 2011 through 2014 — a period when the once-hapless Baylor football program became a dominant force in the highly competitive Big 12 Conference. Baylor’s interim president has said in a statement that he cannot confirm Mr. Clune’s numbers, which followed other troubling figures that Baylor’s board gave to The Wall Street Journal in October: assaults on 17 women by 19 players, including four gang rapes. Collectively, the cases have become a cautionary parable for modern-day college athletics, one in which a Christian university seemed to lose sight of its core values in pursuit of football glory and protected gridiron heroes who preyed on women. In a statement to The New York Times on Monday, Baylor officials said the university was committed to “doing the right thing” — through self-examination, repeated apologies and making 105 recommended changes to its policies and structure. “Our mission statement calls for a caring community based on Christian principles, and any act of sexual violence is inimical to these standards,” the statement said. Even so, the scandal has not sat well in Texas. Last week, the Texas Rangers, the statewide law enforcement agency, confirmed that it had begun a preliminary investigation into Baylor. That announcement came days after a state representative, Roland Gutierrez of San Antonio, filed a resolution urging Gov. Greg Abbott to have the Rangers investigate “the obstruction of justice surrounding the sexual assault of young female students at Baylor University.” And this week, a federal judge rejected Baylor’s request to throw out a lawsuit filed against the university by 10 women who say they were sexually assaulted while they were students. Judge Robert L. Pitman of Federal District Court ruled that each plaintiff had “plausibly alleged that Baylor was deliberately indifferent to her report(s) of sexual assault, depriving her of educational opportunities to which she was entitled.” Rising on Athletic Success For most of her freshman year, Ms. Hernandez was passionate about the Baylor green and gold. A native of Southern California, she came to the university’s verdant campus in Waco to study nursing on an academic scholarship. She loved her teachers and friends, and enjoyed cheering on the ascendant football team — a sudden powerhouse, thanks in part to the likes of her future attacker, Mr. Elliott. She arrived at a time of athletic excellence so bountiful that the 2011-12 school year came to be known as the Year of the Bear. The football team had its first Heisman Trophy winner in the quarterback Robert Griffin III; the men’s basketball team reached the N.C.A.A. tournament’s round of eight for the second time in three years; and the women’s team went 40-0 for the national championship. This run of success was all the more extraordinary for what had come before: decades of mediocrity in major sports, with the lows far outnumbering the highs. Then, before the 2008 season, the university hired Art Briles as its football coach. And things changed. Mr. Briles was Texas to the core — a quarterback for his father at Rule High School, a wide receiver at the University of Houston and a coach at five Texas high schools before he entered the college ranks. Along the way, he devised an explosive offensive system that seemed to attack the end zone on every snap. He inherited a Baylor program that had not had a winning season since 1995. What’s more, schools like Baylor, then a second-tier choice for top recruits in one of the country’s most football-mad states, rarely experience quick turnarounds. But the new coach pulled it off; by his third year, the Bears were winning more than they lost. The university and its alumni responded, reportedly paying the charismatic Mr. Briles one of the highest salaries in college sports and embarking upon a fund-raising campaign that led to the $266 million construction of McLane Stadium — a breathtaking football cathedral that abuts the Brazos River and Interstate 35. Just before the 2014 season, Mr. Briles marveled at the visual and emotional power of the stadium, saying, “Show me something better.” Mr. Briles imagined the impression the sight would leave on an 8-year-old child looking out the window of a passing car. “They’re going to say, ‘Momma or Grandmother, man, look at that place,’” he said. “‘That place is beautiful. Where is that?’ And she’s going to say, ‘Baylor.’ “And then so for the rest of their lives they’re going to associate Baylor with excellence. And that’s hard to come by and the only way to get it is through the production of image. “So our image is good.” The promise of McLane — named after Drayton McLane Jr., Class of ’58, who made his fortune with a food-supply business — helped stimulate capital campaigns that focused on a new scholarship fund and a new campus for the business school. “Success in athletics means that all boats rise,” Kenneth W. Starr, then the university’s president, told The Times in 2014. Mr. Starr had arrived at Baylor in 2010 with a formidable resume and a clear vision. A former solicitor general, federal judge, law school dean and independent counsel — the Javert in the President Bill Clinton sex scandal — he promised an administrative stability that the university had lacked in recent years. He raised Baylor’s academic profile and presided over ambitious fund-raising efforts, all while endearing himself to undergraduates. He was the avuncular “Judge Starr,” leading freshmen on a pregame sprint across the field to invigorate the crowd at each home game. The dynamic pairing of Mr. Starr and Mr. Briles signaled to students and alumni alike that, with the twinning of their respective strengths, Baylor was going places.

Along the way, the university’s football players appeared on giant posters, on computer screen savers — just about anywhere you looked on campus. A larger-than-life bronze statue of Mr. Griffin, midthrow, greeted visitors to McLane Stadium when it opened in 2014. The message was clear: Our heroes. But myriad court cases suggest that as the boats of Baylor rose, to use Mr. Starr’s analogy, standards fell overboard. Baylor and its football program, it seemed, began to value on-field talent above all else. Baylor’s football team signed up transfers with disciplinary issues in their pasts. There was Shawn Oakman, for example, a huge defensive end dismissed from Penn State’s team for stealing a sandwich and grabbing a female store clerk by the wrist. And Sam Ukwuachu, a former Freshman All-American defensive end kicked off Boise State’s team for reasons that were left publicly unclear at the time; his ex-girlfriend later testified that he had assaulted her. (Mr. Briles has said that he was unaware of the assault accusation.)

According to the lawsuit filed by Mr. Clune, the lawyer from Colorado, the football staff at the Baptist institution employed a “‘Show em a good time’ policy,” in which current players offered alcohol and drugs to high school prospects visiting the campus and introduced them to female students.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.