|

Context key for story of bishop and scandal showing Church hypocrisy

Irish Examiner

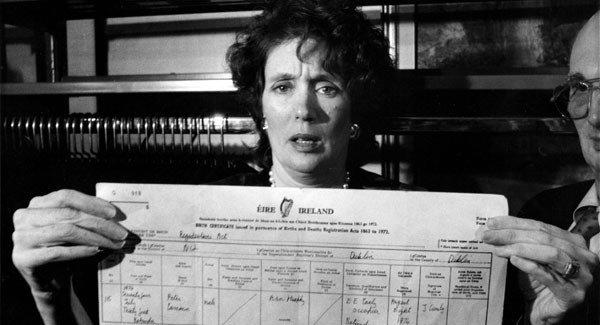

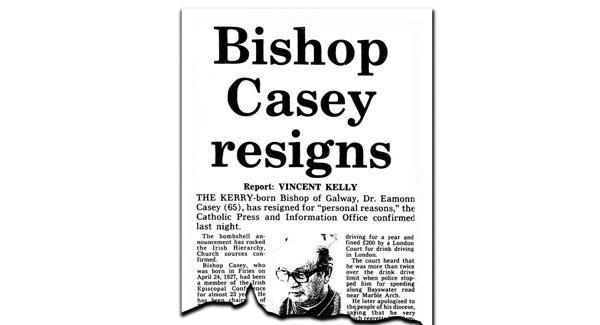

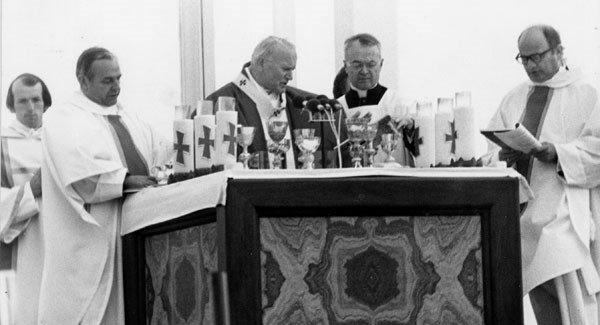

Ireland awoke in May 1992 to shocking news — Eamonn Casey, the popular Bishop of Galway, had fathered a child with an American woman, Annie Murphy, and had fled the country hours before the story of their affair broke. The affair, which began when the 25-year-old New Yorker came to Ireland in 1974 to stay with Casey, who was her father’s distant cousin, was kept secret for 18 years. Annie Murphy was seeking solace in this country after the break-up of an unhappy marriage, and her father arranged for her to stay with Casey, who was Bishop of Kerry at the time. She recalled that when he met her at Shannon, after her flight from New York, he had a “puzzled look”. “Maybe he thought, as a result of my father’s letter, he would be meeting someone gaunt and haggard. Instead, there was this relaxed, slim, young lady of 110 pounds in suede high heels and a flattering mauve dress, with small polka dots.” What followed, as the Phoenix magazine wrote with unrestrained hyperbole on the 20th anniversary of the 1993 publication of Forbidden Fruit, Murphy’s lurid account of her affair with the bishop, was the “arrival in Ireland of Dallas-style sex”. In her 1997 book, Goodbye to Catholic Ireland, Mary Kenny said that the story of the Bishop Casey-Annie Murphy affair was “a scandal unprecedented in Ireland for 200 years” — a scandal that left people flabbergasted and disbelieving. Much bigger scandals were still to come, with far more damaging consequences for the Catholic Church. But in 1992 the story of the bishop who ran when he knew the Irish Times was about to reveal details of his affair and tell how he used diocesan funds to pay off claims made by the mother of his son, was sensational stuff. With the publication the following year of Forbidden Fruit (which Murphy co-wrote with Peter de Rosa), many more details, all of which were deeply upsetting to a Catholic population accustomed to holding bishops in high regard, came into the public forum. It was Peter Murphy, the son born of the affair and who Casey had never publicly acknowledged, who eventually forced the bishop to break his silence and own up to his responsibilities. A decision was taken to finally go public, and the full story of the affair was given to Conor O’Clery, who at the time was the Washington correspondent for the Irish Times. It would be one of the biggest stories ever to hit Ireland, O’Clery told Murphy. And he was right. Days after the story broke in May 1992, and after Casey’s resignation as Bishop of Galway had been accepted by Pope John Paul II, O’Clery rang Murphy from Dublin to tell her Casey had issued a “dramatic statement” in which, for the first time, he admitted paternity, saying Peter was his son. In the statement, Casey also admitted that he had paid the sum of IR£70,669 — from the diocesan reserve account — to Murphy in July 1990. He then added that this sum had, since his resignation, been paid into the diocesan fund on his behalf by “several donors”. The shameful cover-up was finally ended. In a TV3 documentary aired in August 2013 and entitled Print and be Damned, reporter Donal MacIntyre said: “The fall from grace of Eamonn Casey was the first crack in the edifice of the Catholic Church in Ireland.” There are elements of real tragedy about that fall from grace. Casey, a man of unbounded energy, had made a great contribution to the Church and had much more to give. Ordained in 1951 for the diocese of Kerry, he was appointed chaplain to St Ethelbert’s parish in Berkshire and became the first chairman of Shelter, the UK housing charity where he came to the attention of Cardinal John Heenan, Archbishop of Westminster. Partly through Heenan’s influence in Rome, Casey was appointed Bishop of Kerry in 1969. In 1973 he was a founder and first chairman of Catholic aid agency Trócaire. Through his work with this agency, he developed a keen interest in Central America, and he became a critic of American policies there, where the Reagan administration was supporting repressive regimes and sponsoring death squads. One victim of these squads was Oscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador. Casey attended his funeral in 1980, and when Mr Reagan visited Ireland in June 1984, Casey pointedly refused to meet him. The sad thing is that most of the good he did has been forgotten, and his one big mistake — having a son while Bishop of Kerry — is probably the only thing people will remember about him. Could he have handled things differently in 1992, instead of fleeing to the States? Could he have handled things differently back in the 1970s on first learning that Annie Murphy was pregnant with his child? Of course he could. In 1992, when he knew the game was up, instead of running he should have stood his ground, called a press conference, and had his say. There was a vitality about him that was striking, and he had a magnetic personality. He was the embodiment of the American can-do attitude, the conviction that there is no such thing as an unsolvable problem, and with the drive to match that. Colourful and voluble, he could talk as only a Kerryman can talk, which is why he was a natural for television hosts like Gay Byrne. In the run-up to an All-Ireland football final, I was sent to Kerry by the Irish Press to interview three people for a colour piece: Paddy Bawn Brosnan in Dingle, John B Keane in Listowel, and Bishop Casey in Killarney. Of the three, by far the most colourful and entertaining was Casey, and that’s saying something given the company I was keeping. But Casey had his faults. He had a big ego and was overly fond of the limelight. Behind the bonhomie he could be arrogant and overbearing, not unusual traits in Irish bishops. And he was too readily attracted to what the Italians call la dolce vita. He liked fine wines, good cigars, and fast cars. Later, his critics would say that an involvement with a woman was inevitable. And it was the arrogance that enabled him to live with the hypocrisy that was an inevitable component of the 18-year cover-up and the secrets that he harboured during that period — a period during which he continued to operate under the moral mantle of a bishop. Of all the Irish bishops, Casey was the one who impressed Pope John Paul II the most during his visit to Ireland in 1979. And Casey alone had the honour of hosting a dinner for the pope at his Galway residence. Throughout all this, of course, Annie Murphy and the son she bore him were well-kept secrets. During that visit, there was also of course a sickening display of hypocrisy at Knock when, during the prelude to the Youth Mass, Casey and Fr Michael Cleary (both of whom had fathered children) entertained the vast crowd while waiting for the papal helicopter to arrive. All of that said, the subsequent treatment of the fallen bishop was disgraceful. Casey, who said in an interview in 2007 that he believed in “God’s forgiveness and healing”, was shown very little forgiveness by the Church to which he had committed his life. He found little support among members of the Irish hierarchy, an exception being Bishop Willie Walsh of Killaloe (now retired). Little wonder that, in the 2013 TV3 documentary, Peter Murphy, who was 38 at the time and had been reconciled with his father, said he felt the way the Church had treated his father “was ridiculous — especially with what has come across our eyes in the past 17 years — all the paedophile scandals. To tell the truth, I felt this from the get-go. What did the guy do? He had an affair.” Some of his fellow bishops could scarcely conceal the schadenfreude they experienced when Casey fell from grace. Yet among them were some who were guilty of far greater sins than an affair — sins involving the complicity in the covering up of sexual abuse of minors by clerics. Surprisingly, in an interview with Tralee historian and broadcaster Maurice O’Keeffe, broadcast on RTÉ’s Morning Ireland in January 2007, Casey said Pope John Paul II did not want him to resign as Bishop of Galway when he went to Rome to do so in May 1992. “It was heartbreaking,” said Casey, who was 79 at the time of the interview. “The Holy Father didn’t want to accept it.” Casey added that he resigned because he wanted “to get out before the media descended on me”. In any case, if the Pope didn’t want him to resign then why did he sanction the ban on Casey saying Mass in public, a ban that remained for the rest of his life and which caused him great hurt? In a letter to the newspapers in 2008, Fr James Good of Cork, who himself had been forbidden to act publicly as a priest in 1968 when he publicly dissented from Humanae Vita, Pope Paul VI’s anti-contraception encyclical, described Casey’s treatment as “a disgrace”. The subtext to the Casey story touches on the imposition of mandatory celibacy on all candidates for the priesthood. There is an honourable rationale for celibacy, but it is not for everyone who wishes to become a priest. Today, there are many men who left the priesthood because they wished to marry, but who would be happy to return to active ministry if the Church lifted the ban on married priests. The saddest feature of the Casey story was the loss not just to the Irish Church, but to the wider society, of someone of his energy, commitment, and vision. Yes, it was largely his own fault, but everything has a context.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.