|

Searching for My Sister’s Murderer: Fla. Woman Breaks Silence on Nun’s Mysterious 46-Year-Old Death

By Adam Carlson

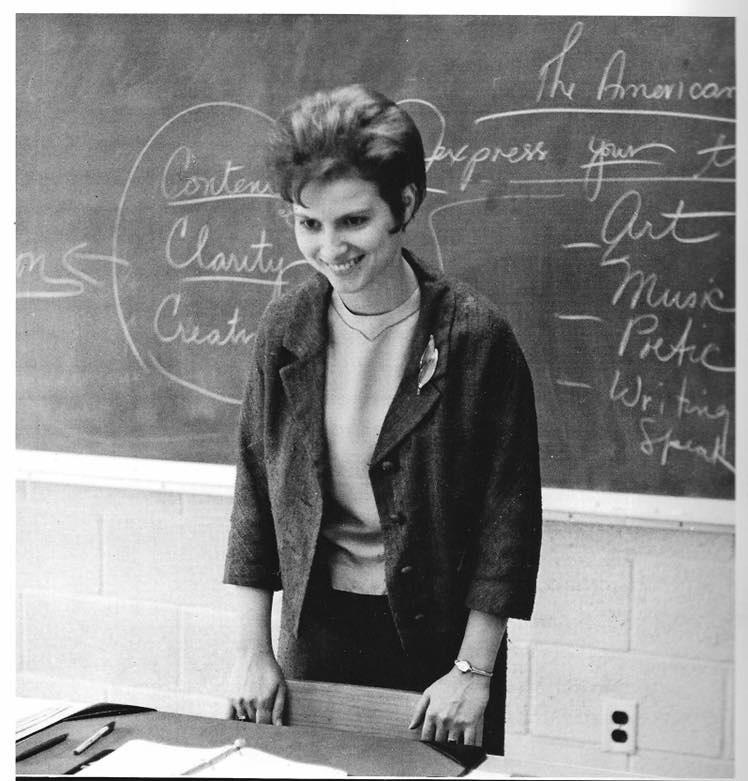

[with video] Marilyn Cesnik Radakovic’s journey to find out what happened to her older sister began nearly 50 years ago began last year when she read a news article with the headline “Buried in Baltimore.” “And I looked at my husband and I said, ‘Oh my God,’ ” Radakovic remembers now. It was early 2016 and the couple was at the California apartment of Radakovic’s mother, who had recently died. In the process of cleaning out her belongings, Radakovic discovered her mom had collected years of articles about the death of her eldest daughter, Radakovic’s sister, 26-year-old nun Sister Catherine “Cathy” Cesnik. Cesnik was found on a freezing January day in 1970 in Baltimore County, nearly two months after she vanished near her apartment. Her body was partially naked and her head had been bashed in, but there was little physical evidence at the scene. The homicide remains unsolved, and for decades Radakovic believed Cesnik was the victim of a “wrong place, wrong time” crime. But reading through her mother’s things — the 2015 Huffington Post story was the first clipping she found — Radakovic learned about the swirl of rumors and theories that still surrounds Cesnik’s death. “I was shocked, I was so shocked,” Radakovic tells PEOPLE. “That was the first time I had learned of any of this.” As she would discover, there are many people in Baltimore who believe Cesnik was killed because of what she may have known: that the all-girls Catholic high school in Baltimore where she had taught English, Archbishop Keough, had a history of sexual abuse. “I think Cathy was planning to go to the police about what was happening to us girls at Keough,” says Jean Wehner, one of her former students, “and [she] was killed to keep that from happening.” • For more on Sister Cathy’s mysterious death and the secrets she may have been killed to keep, subscribe now to PEOPLE or pick up this week’s issue, on newsstands now. There was another twist to come: After Radakovic buried her mother, she dug deeper into her sister’s case … and found that a documentary team was already doing the same thing, and had been for more than a year. That documentary series, The Keepers, premiered on Netflix on Friday with Radakovic as a key participant. Director Ryan White tells PEOPLE Radakovic was little more than an “urban legend” for his team as they worked on the documentary, as no one had been able to confirm Cesnik had any siblings. But a Facebook message ultimately connected them, and Radakovic features prominently in the later episodes. “Marilyn had the blinders ripped off in a very scary way, I think, that what she thought happened to her sister might not be at all what actually happened to her sister,” White explains. White describes Radakovic as “very brave, very outspoken, very direct — and now, I would say, very, very driven to get answers.” In her first interview about Cesnik, Radakovic speaks to PEOPLE about who her sister really was, what the decades after her death have been like and her renewed quest for answers. ‘There Was Only the Two of Us’Radakovic still tears up when she talks about Cesnik, who died more than 46 years ago. But her love is evident, too, for the woman she was so proud to have as her sister. Six years Cesnik’s junior, Radakovic grew up as her tag-along and daily charge, as Cesnik babysat while their parents worked. “There was only the two of us for a long time, so we were really close,” Radakovic says. “We shared a room until she went into the convent. She was very, very, very important to me.” Cesnik felt called by God to be a nun, her sister says, and she had a gift for teaching. (Radakovic was, in many ways, her sister’s first student.) A Pittsburgh native, Cesnik headed to Baltimore at 18 to join the School Sister of Notre Dame, a religious order whose nuns had taught her in grade school. “When she first went in [to the convent], they had visitation days and my parents and I always went down for the visitation days, we never missed them,” Radakovic says. “And they used to — it was horrible, it was just horrible, because I hated to leave, hated to leave. They’d ring a bell and [the girls] were required to get up and just walk away.” But Radakovic couldn’t let go. “I would hang on to her, and she was like, ‘You’re gonna get me thrown out!’ ” And she’d tell Cesnik, “‘That’s what I’m trying to do, Cathy, I’m trying to do.’ I’d say to my dad, ‘Get the car, we’ll steal her.’ ” In the ensuing years, the sisters stayed in touch via letters and phone calls. “And every time she came back home — oh my gosh, it was like Christmas,” Radakovic says. ‘She Wanted to Be More’In 1969, at 26 years old, Cesnik faced an impasse in her life and career, Radakovic says. “She wanted to be more. She wanted to do more than she was able to do within the confines of the order,” Radakovic says. “And this was how she had explained it to me. She thought she had more potential than they were allowing.” The fall before she died, Cesnik transferred from Keough to a local public school in Baltimore and had asked for a leave of absence from her order. She moved into an apartment with another nun and was weighing her options. “She had a very soft spot in her heart for the School Sisters of Notre Dame,” Radakovic says, “but I think she felt she was called to do something other than live in the convent.” The last time Radakovic saw Cesnik alive, her older sister had returned home to Pittsburgh to explain to her family what she was thinking and her potential plans. They talked about Radakovic’s impending college graduation and that she might move to Baltimore and stay in Cesnik’s apartment. Months later, Radakovic became engaged (to the man who is still her husband) and she called Cesnik to ask her to be her maid of honor and discuss details of the wedding. Days later, after an engagement party with her then-fiancé’s family, Radakovic got a call from her mother. “She said, ‘You need to come home right away. Something has happened to your sister.’ ” As The Keepers details, Radakovic’s engagement may have been one of the last things on Cesnik’s mind before she vanished while shopping on Nov. 7, 1969. Among the other errands she ran that night, Cesnik was also looking to buy a present for her sister. ‘Always Keep Cathy Alive’Cesnik’s body was found on Jan. 3, 1970. In the nearly two months between that discovery and her disappearance, Radakovic, then 20 years old, remained certain her sister was alive somewhere. Her hope clung to a strange letter she had received in the mail, apparently sent by Cesnik and postmarked the day after she went missing. The letter’s contents and its link to the case, if any, have never been confirmed by police, though the family turned it over as evidence soon after Radakovic got it. “We went through Christmas with Cathy being missing, and that whole time — because I had gotten that letter — I was sure she was alive,” Radakovic says. “And I had spent time trying to convince my parents, ‘She’s alive, let’s find out what the letter says, she’s tellin’ us where she is, we need to go, we need to find her, we need to help her.’ ” “I don’t think we thought she was dead,” Radakovic remembers. “I mean, my mother loved eating chocolate, and I remember distinctly my mother said, ‘I’m gonna give up chocolate until Cathy comes home and then I’m gonna eat chocolate until I get sick.’ ” • Want to keep up with the latest crime coverage? Click here to get breaking crime news, ongoing trial coverage and details of intriguing unsolved cases in the True Crime Newsletter. The discovery of Cesnik’s dead body rocked the family. In the immediate aftermath, as they made preparations for her funeral, Radakovic was given a piece of advice by the head of Cesnik’s convent: “It is your job, Marilyn, to always keep Cathy alive. And as long as you’re alive, Cathy will be alive and don’t ever forget that.” Nine months later, when Radakovic got married, she didn’t throw her bouquet, instead leading everyone to the cemetery to put the bouquet on Cesnik’s grave. When her daughter was born five years after that, Radakovic named her Catherine. Can the Case Be Solved?Since her mother’s death last year, Radakovic has been her family’s point of contact with Baltimore investigators, who tell PEOPLE the homicide case is “quite active.” Though she spent years in the dark, Radakovic is now regularly in touch with cold case detectives after first meeting with them in the spring of 2016. Their interactions have sometimes been fraught, and she tells PEOPLE, “There’s a lot that we still would like to see them do.” County police, meanwhile, say they have never proven that Cesnik’s homicide was due to any knowledge she had of the Keough sex abuse — though it is one of multiple theories they are pursuing, including possible links between her death and three other unsolved homicides in the area around the same time. The Keough priest who allegedly masterminded the sex abuse, Father A. Joseph Maskell, died in 2001 and denied the abuse accusations before his death. He was never charged. The church first learned of the allegations in 1992 and removed Maskell as a priest in 1994, as soon as it had corroborating accounts of his abuse, according to Sean Caine, a spokesman for the Archdiocese of Baltimore. Caine says the church believes Maskell — who overlapped with Cesnik while at Keough, where he worked as the school chaplain and counselor from 1967 to 1975.— was sexually abusive. The exact number of his victims remains unclear. There is one living suspect in Cesnik’s homicide, according to police spokeswoman Elise Armacost. But officials have declined to identify that person. “We still remain optimistic that it’s possible for us to clear this case,” Armacost says. White, the Keepers director, said nearly the same thing in a separate interview. Radakovic, now in her 60s, remains determined. “Everything I’ve done, I’ve really tried since that time — which is just a little over a year ago for me — I’ve tried to give them all the information that I’ve learned,” she says of working with authorities. “And everything ends with, ‘I want you to do your job.’ “

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.