|

Survivor’s court case could win damages for residential schools intergenerational harms

By Paul Barnsley

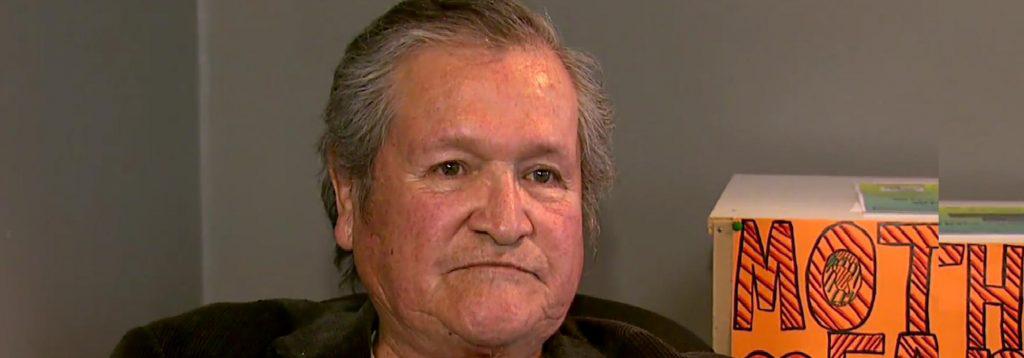

As the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) nears completion, a potentially explosive case brought forward by a former national chief is slowly making its way to court. Del Riley, who occupied the national chief of the Assembly of First Nations’ office from 1980 to 1982 – during the final days of negotiations that led to Aboriginal rights being enshrined in Canada’s newly-repatriated constitution – refused to participate in the IRSSA. He saw the settlement agreement as too limited – so he hired the London law firm Harrison Pensa to sue the federal government and the Anglican Church of Canada. Riley aims to expand the scope of the defendants’ liability as he seeks compensation for his time at the Mohawk Indian Residential School in Brantford, Ont. The statement of claim, filed in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in London, Ont. in 2010, seeks $4 million in damages for breach of fiduciary duty. Riley is also seeking to get a court to acknowledge that his children were harmed because of the abuse inflicted on him, something called inter-generational harms, which were excluded from the settlement agreement. The lawsuit cites the Ontario Family Law Act in claiming damages for Riley’s adult children – Delbert Leonard “Len” Riley Jr. and Melanie Sadie Debassige — for “loss of care, guidance and companionship” from their father due to the psychological harm he suffered as a student.

Even though it may have been called a school in the minds of the government, it wasn’t really a school. It was a prison camp for small children. – Del Riley

Riley alleges he was sexually abused for three years by a dormitory supervisor working for the Anglican Church, which ran the school under an agreement with the federal government. He decided not to sign on to the IRSSA early on. He thinks too much was bargained away in the settlement agreement. He would have been subject to the Independent Assessment Process (IAP), which governs how former students are compensated for sexual and severe physical abuse. “I’ve spoken to probably well over 100 people that have gone through the IAP and all they have is nothing but complaints,” he said. “They dealt primarily with three or four abuses. And if you got three or four, you were getting a lot. But as far as I can see, this might be 10 per cent of the part that I’m suing for, and it’s just a small portion of any kind of court settlement. The big part is the breach of fiduciary, and the breach of treaty.” He acknowledges that having a Canadian judge hear a case where Canada is the defendant has its risks. But he’s going to take the case forward. “Even though I realize at this point that 30 per cent of our people are sitting in the white man’s jails. So, the worry, I’m on pins and needles. And can I get a fair trial in Canada?” he asked. Riley believes the government was in no hurry to have his case get to trial. “This is a whole travesty of justice for me because they put me last. They could have put me first. But here’s what would have happened. Because I’m going to regular court, the items that I’m suing for in the court document are way beyond what they would have allowed you in the IAP. Like they don’t allow you to sue for loss of language, for loss of culture, breach of fiduciary, and a whole host of other things,” he said. “But the real issue here is, does fiduciary extend to my kids? Because they had a fiduciary responsibility to me, because of the racist Indian Act and all of the restrictions and things they imposed on First Nations people under the Indian Act. And the legal obligation I had to go to this school. So I’m saying that, and it’s my legal advice as well from legal people, that, yeah, fiduciary extends to my children too. As it should to all of the children across Canada who had parents that went to residential schools.” Riley believes the government took its time responding to this lawsuit because a result in his favor would have been led to some difficult questions. “They don’t want to be embarrassed by anything that could potentially come out as opposed to what they did in the IAP. Because people are going to compare this case to the IAP. And then everybody’s going to go, OK, well, hey, how come he got that and we couldn’t? You’re going to have lots of questions,” he said. He said conditions at the school were horrible and the government knew it but did nothing. “Even though it may have been called a school in the minds of the government, it wasn’t really a school. It was a prison camp for small children, starting at five. It was a place where the kids were literally starved in there,” he said. “They didn’t have enough food for us. We were always hungry. And I think anyone you’ve talked to, you’ll find that’s probably the same case. Always hungry. So in order to supplement that, we would always have to go and dig in the dump, local dump. There was just maybe a half mile away or so, or a couple “There was just maybe a half mile away or so, or a couple kilometres away and the other was, we were confined. So this was a prison. This was actually a federal prison. I don’t know why they even call it a school. It wasn’t a school because we were confined. And we were beaten. There’s was a lot of beatings. I took a lot of beatings. And a lot of times for things so minor that you wondered why they would engage in things like that.” Last year, Riley, frustrated with the slow pace of his case, changed law firms. He is now represented by former Ontario premier and interim federal Liberal leader Bob Rae, who is a senior partner at OKT – Olthuis Kleer Townshend LLP in Toronto. Rae toured the former residential school with Riley. He has no doubt that his client was physically and sexually abused there. “The issue for me is, what is the continuing legal obligation of Canada, with respect to its . . . the Crown has a fiduciary obligation. There’s an obligation to take care of the people who are treated in that way,” said Rae. “They didn’t take care. There was clear negligence on their part. And the church had an obligation, which, not only negligence on their part, but actually people who worked for the church and who were representative of the church committed the abuse. So when you put those things together, you have what I think is without any question, a very strong legal claim.” The lawyer was not nearly as quick as his client to conclude the government had delayed the case for political reasons. He said the government had attempted to negotiate a solution. But the government was in a unique position. “I mean this is where the Crown has two roles, right? The Crown is a defendant for what happened, throughout many decades of what happened in residential schools. But in this case, the Crown is also the government, which has an ongoing responsibility. Because the Crown’s responsibilities, the honour of the Crown doesn’t suddenly evaporate when you’re a defendant in court. Even when you’re a defendant in court, you still have to act honorably and effectively in defending the interests of the First Nations,” he said. “That, I don’t think has always been followed by the Crown. I think that’s an ongoing challenge.” Regardless of the outcome of Riley’s court action, those who participated in the settlement agreement will not see a benefit. “No. The hard fact is that if you’ve been part of the class action and you settled as a result of the class action, then you accepted the settlement payment that was worked out under the class-action scheme that was established by the federal government and the churches. That’s it,” Rae said. For more on the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement – click here: Truth? Or Reconciliation? After he left politics, Rae joined a law firm that specializes in Aboriginal law. He has no doubt that there has been inter-generational harm. “So we need to understand, the residential school experience was not a 10-year problem, or a 15- or 20-year problem. This is something which lasted for, well, if you go back to the very first residential school and you come to the one last was closed, 160 years. And that’s a long time for inter-generational damage to have been done. And it’s been done for a long time. And that, I think, helps to explain the level of pain that we see in communities. “And if the people don’t think there’s pain in these communities, they haven’t talked to people. They haven’t visited the communities. Because these communities are deeply troubled places, and we need to understand why. How has that happened?” he said. Contact: pbarnsley@aptn.ca

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.