|

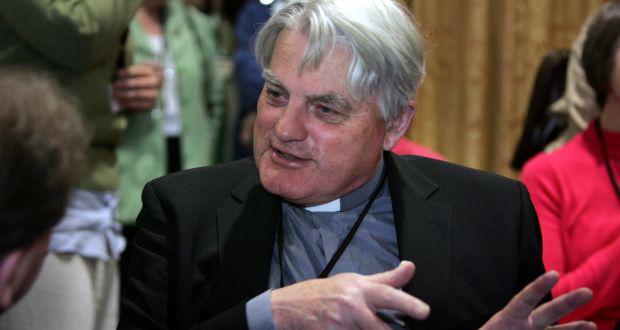

Church vows were ‘like putting a manhole over the sewer’

By Patsy Mcgarry

Former Glenstal abbot says pandemic of child abuse and incest is a ‘religious problem’ Moralising will not help us understand the wave of sexual harassment and child abuse cases that have emerged nationally and internationally, says Mark Patrick Hederman, former abbot of the Benedictine monastery at Glenstal, Co Limerick. Instead, he believes we must look at the human passions that connect people such as Harvey Weinstein and Tom Humphries. “We’ve had three philosophers of the 20th century that decided there are only three basic energies that move us all. One is power, the other is sex, and the other is money.” While this does not capture the full picture, “it’s a good beginning... The world goes round because of sex, said Freud; or money for Marx, and power for Nietzsche,” he says. “The church had found that out in the Middle Ages and they said: ‘We’ll put three stops on those three things – poverty, chastity, and obedience.’ So they put vows over them. It was like putting a manhole over the sewer. It doesn’t work like that.” Ruffled feathersFr Hederman, who last year completed his term as abbot at Glenstal, ruffled some feathers in the Catholic Church last week when he appealed to priests to stop calling their bishops “spineless nerds and sycophantic half-wits”. Next week, he is giving a talk at Dublin’s Smock Alley Theatre entitled “what Ireland needs to nurture its soul”. Speaking to The Irish Times in advance, he says religion is “absolutely essential for us. Connecting with the spiritual is vital to our whole culture now and when it disappears you’re into drugs and alcohol, everything that will block everything, or suicide”. Or criminal activity, he adds. “With Kevin Spacey and all these people, you get to a point where your whole life is destroyed. Tom Humphries again. We’re all moralising about this and saying: ‘Oh these are the lowest of low.’ The real truth is what were those people looking for? I don’t know but it is a religious problem, that’s what I’m saying.” It is not about “judging or condemning – it’s a finding out. And I’m absolutely certain in every one of those cases it’s spiritual. In other words, those people were trying to achieve something at a level which was carnal and which should have been spiritual.” The idea “that we can all sit and moralise about it and say, ‘Oh they are dreadful’, I mean, that’s all of us. We’re all in the same boat. It’s not as if they are monsters. These are all people and we’ve all got the same humanity.” ‘Ending of taboos’In Ireland, he says, “we’ve had a huge liberation but the trouble is that every culture – no matter what you’re talking about – they all had a taboo about incest”. That was now gone, he says. “We had a culture here and it was very repressive but at least it was a taboo.” Nowadays, “every child in fifth year wants a child, and they don’t want a husband either. ‘We’ll get a sperm bank.’ We’ve gone to a stage now where it’s so completely devoid of all notion of morality, everything. It really is a tsunami.” He says: “There’s a pandemic now of child abuse and incest and actually what people are looking for is that rebirth which is in Christianity... Most people are looking for a second half of life, something which will allow them to be reborn and many of them see that in a child or they see it in a younger person. “What’s so terrible is that instead of actually finding the religious answer to that – which is to do with going to another level symbolically to become reborn – they’re allowing their instincts and their impulses to lead them into crime.” Psychologically speaking, he says: “Incest is actually calling us. It’s part of mid-life. It’s one of the most experienced fantasies in people’s lives and it’s calling them to the second half of their life. It’s calling them to the rebirth which Christianity and every other religion talks about”. Of his own calling in recent years, Fr Hederman says: “I never wanted to be a priest, never had the vocation.” It was a requirement of taking up the position of abbot to which he was elected to his “complete and utter surprise” in 2008. The ordination was just a month after his election “so the church can fast-track whenever the moment requires it”, he says. During his term “everybody else was doing all the work. The community was so sympathetic to me as an elder,” he says. “It was a bit like Yes Minister or Yes, Prime Minister in that the guy who is now abbot (Fr Brendan Coffey) was the prior. He was Humphrey to me.” ‘Overreaction’Raising the issue of the Humphries case, he felt the coverage in The Irish Times “was a kind of overreaction, where you’re kind of guilt-ridden or something like that”. Humphries “is a human being. He is destroyed at the moment and he becomes a kind of scapegoat and he becomes the pariah. All of that is wrong in terms of society. “We’ve got to understand this is our problem and that nobody, as the ancient Romans said, ‘nothing human is alien to me’. That’s what we have to come to terms with.” He felt “we’re not dealing with the situation. We’re actually sensationalising it and making it a form of entertainment.” Instead “of just punishing people and moralising about it and condemning them, it’s a question of making them understand so that they can move on. “It’s certainly possible. The big, big religious movement of the 20th century was the AA [Alcoholics Anonymous] and the basic principle of that was that you have to recognise what you’ve done.” PariahsA “sympathetic counsellor – that’s what you need to have. Locking people up in prison where they torture one another, that doesn’t do any good at all. They’re pariahs when they come out and nobody wants to have them in their vicinity.” There has to be “an attempt to reintegrate them to their own humanity and that’s what spirituality is. That’s what the incarnation is about: that we are human beings but there is a hope and that there is nobody without hope.” He does not think young people need religion very much. “They’re perfectly happy and they’re delighted with themselves. Most of them don’t even think about religion or church until they get married, have their own children,” he says. Then “things happen where you need another dimension and you’re aware of another dimension”. In general, “we’ve gone from one extreme to another and we’re using very blunt instruments – a legal situation where one size fits all – for dealing with things which really require very careful and very personal counselling”.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.