Monk Who Abused Children on "Crime Free" Caldey Island for Decades

By Amanda Gearing

Summer holidays on Caldey Island were seemingly idyllic. The tiny island off the Welsh Coast at Tenby is a place of beauty and holiness, with bluebell woods, clifftop walks, tea gardens and picturesque beaches. Pilgrims come for religious retreat, staying in the island’s cottages, joining the monks in prayer at the imposing Italianate Abbey of Our Lady and St Samson. In November last year Caldey Island’s reputation for quaint charm was shored up by reports of the “only crime in living memory” to be investigated by police – when a father hit his seven-year-old son for misbehaving in the chocolate shop. The father faced court and got a fine; the monks were reported to be “concerned” about the island’s “crime of the century”. For Emily those news reports were like a “punch in the stomach”. Some of her earliest memories are of an altogether more serious crime: being sexually abused by one of the monks, a predator called Father Thaddeus Kotik.

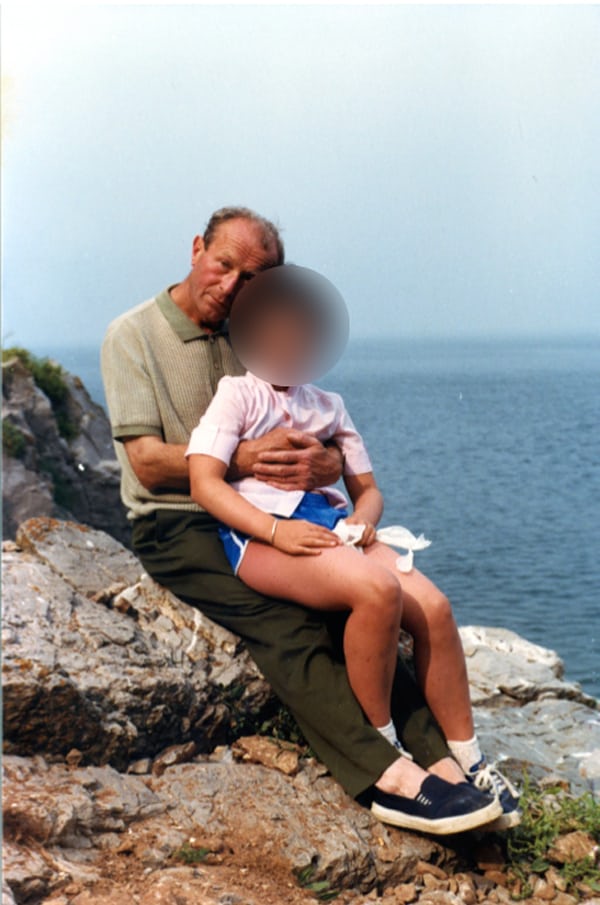

Emily is one of three women who have spoken to the Guardian about being sexually abused by Kotik as children during the 70s and 80s. (The women’s names have been changed to protect their identities.) In August last year the women launched civil proceedings against the order, claiming personal injuries. The court documents say Kotik offended against the six girls between 1972 and1987, though the women believe there may be many more victims, over many more years. A former soldier who fought in the Free Polish army during the second world war, Kotik moved to the island in 1947, joined the strict Cistercian order and was ordained a priest in 1956. He lived on the island until his death in 1992. It appears he was never questioned by police and that they were not informed until 2014. Assigned to work in the abbey’s dairy, Kotik befriended the families who regularly visited the island along with the handful of farming families who lived there. He gave them handmade chocolates and fresh produce, and invited the children to the dairy. After gaining the trust of the devout Catholic parents, Kotik preyed on their daughters, luring them to places where there was no risk of detection – a room beside the dairy, on walks through the woods or in isolated rocky coves near the beach. He volunteered to babysit while their parents went out, pulling the sleepy girls from their beds to sexually assault them. Kotik also lured young children to the monastery garage where he kept a chest full of sweets. Once inside the garage, he would lock the door, allow the children to eat as many sweets as they wanted, while he lifted them to his lap, removed their clothes and sexually assaulted them.

Over at least two decades during the 1970 and 1980s, some children complained to their parents. Some of the parents and monastery staff also complained to the head of the abbey. In the late 80s, when she and her family were residents of the island, Emily, then five years old, told the then Abbot Robert O’Brien – who died in 2009 – about Kotik assaulting her. The abbot ordered Kotik to stay inside the monastery enclosure, but Kotik regularly escaped from the monastery grounds and continued to abuse children. In 1990, after her family had moved to the mainland, Emily reported the abuse again, this time to staff at her school in Wales. The principal of her Catholic school in Swansea wrote to O’Brien about what Emily told him. O’Brien wrote back apologising and pleading leniency for Kotik because of his war service, saying he had told Emily that Kotik “hadn’t meant to hurt her”. He said he believed the contact between Kotik and the children comprised of “touches through their clothes”. According to the women the Guardian spoke to, in at least two of the cases the abuse was penetrative. O’Brien conceded that Kotik should be reported to police if any of the children “was subjected to sexual violence”. He wrote: “I summoned Fr Thaddeus and warned him of the wrong he was doing the children and the danger. He was very contrite, assured me it had gone no further. I tried to keep an eye on his goings and comings. I think he did improve a while.” ‘God has forgiven everyone’ Charlotte, another victim, and her family had been frequent visitors to Caldey Island from their home in Scotland when she and her older sister were little. Kotik followed his modus operandi, gaining the trust of Charlotte’s parents and taking their daughters for picnics on the beach where he would assault them. Their earliest memories of the island are of being abused by Kotik. He terrified them into silence, telling the girls that if they told anyone about what he was doing, their parents would not want them anymore and would leave them behind on the island with him. The abuse only stopped when the girls’ parents moved to Australia in 1985. Too frightened to speak to their parents, the girls reported the offences to the principal of their school, St Phillip’s Christian College in Newcastle, New South Wales in the late 1980s. According to Charlotte the deputy principal Richard Rule, who now runs a child care centre, prayed for the students and told them they “didn’t need to talk of this again because God has forgiven everyone”. In a 2014 letter she wrote to the school’s current school principal, Graeme Irwin, Charlotte expressed anger that Rule’s failure to report to police deprived Kotik’s victims of seeing the offender charged and convicted. “If the police or my parents had been properly informed back then, I may have had the chance to live the rest of my life without bearing the weight of my guilt and confusion on my own, with all the destruction to your soul that that brings,” she wrote. “Back when my sister and I came forward, the perpetrator was still ALIVE. He could have been dealt with by the law and incarcerated. “That would have stopped him from continuing to abuse other children.” Rule admitted in a statement in February this year that Charlotte disclosed the offences to him in 1989 or 1990. He told the Guardian he was not aware that teachers were expected to mandatorily report suspected child sexual abuse, although it became law in New South Wales in 1988. “I think in terms of showing care we did our best to show care and concern. Because of our knowledge now there is a tremendous amount of sadness. There was a lot of cover-up happening, we realise now. I’m 55 now and you can see the devastation that has created. As young teachers we didn’t understand the severity of what was happening. “I didn’t think to report. It just wasn’t anything we as young teachers were told to do,” he said. Also in 2014, Charlotte emailed the current abbot of Caldey Abbey, Brother Daniel van Santvoort, seeking an acknowledgment of the crimes committed against her and her sister. “The effect that this abuse has had on me has been quietly catastrophic,” she wrote. “Father Thaddeus’ perversion has left me with ongoing feelings and experiences of severe anxiety, fear, guilt and sadness. “I have lived my life feeling a deep and misunderstood level of self-hatred and an inability to trust and believe in another person truly loving me.” No secret But it wasn’t the first time van Santvoort had heard allegations against Kotik. In a sympathetic response to Charlotte he wrote: “I have heard occasionally about this serious matter as regards Fr Thaddeus”. Van Santvoort told her the monastery knew about the monk’s offences and that he had been reprimanded and banned from contact with islanders and visitors in the 1980s, but had not been reported to police. “I am fully aware now of this terrible criminal offence and Fr Thaddeus should have there and then been handed over to the police – something that never happened.” When Charlotte asked if he was aware of any other victims, he responded that Charlotte’s cousin Adele made contact with him four years earlier with similar allegations. Charlotte was shocked, but also relieved that her own experience was finally recognised. “It seems the secret I thought I had been hiding so well was not a secret to the monastery,” she said. Van Santvoort forwarded Charlotte’s emails to police and Charlotte then heard from Tenby police. She wrote a formal statement and submitted it to them, but she heard nothing further. Tenby police have not responded to requests for comment from the Guardian. In a subsequent email, van Santvoort admitted the abuse by Kotik had been “going on for years”. In June 2014 he flew to Australia to personally apologise to Charlotte, her sister and their parents. For Charlotte, who had endured a lifetime of anguish, issues with trusting authority, and a poor relationship with her parents, it wasn’t enough. She decided to to take action, becoming the lead plaintiff in the high court case, a decision, she said, that was not based on bravery but a driving necessity to expose the truth. “It was utter desperation,” she said. “If I didn’t proceed I couldn’t face my life any more.” Opportunistic The admissions by the current abbot also gave Charlotte courage to find the other victims: “I knew my sister and I were not the only ones … Father Thaddeus was opportunistic. In the summer, boats arrived every hour, full of day trippers. I feel that this may be a much, much wider problem than just myself and a couple of other children who we know were affected.”

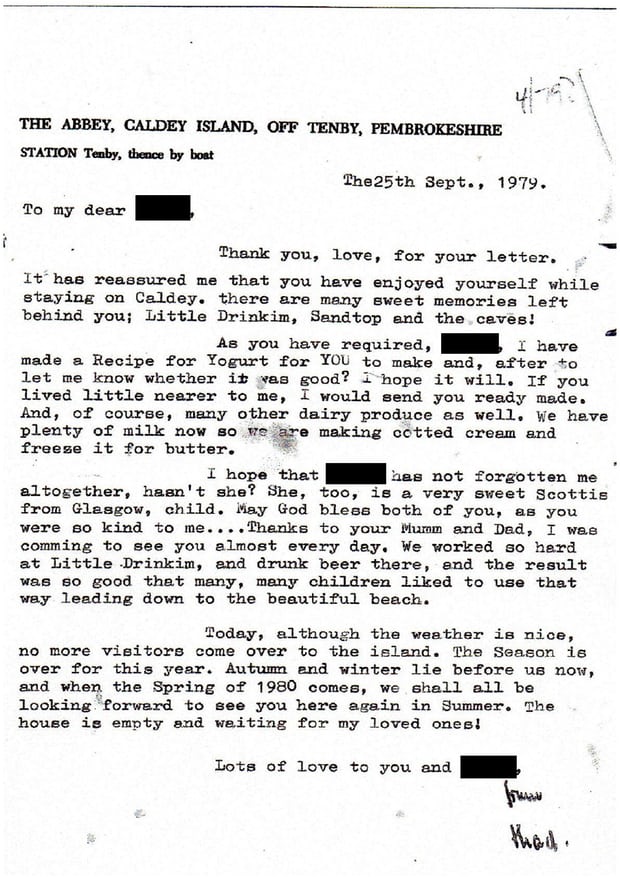

Charlotte searched social media platforms and found her cousins and other unrelated children she knew who had lived on or had been taken on holiday to Caldey Island. In her first tentative email to her cousin Adele, Charlotte told of her determination to expose the island’s sordid secret after realising that she had spent years trying to forget the abuse, rather than confront it. “The time for trying to forget it has long passed, because it doesn’t work. It just eats you up until you face it head on,” she said. “It has been the most isolating, upsetting and lonely journey so far trying to bring this to light. I am sorry that you had to endure what you did. I was lucky to emigrate and escape more years of abuse.” Charlotte discovered Adele had reported the abuse to her family during her childhood and later in her 20s, but her relatives persuaded her not to take legal action. When Charlotte and her sister decided to proceed with their quest for justice, Adele and her sister decided to defy their family by joining the action. Their case was further girded when Emily, who suffered bouts of depression, self-harm, eating disorders and anxiety and who decided not to have children as a result of the impact of the abuse, joined the action. “The effect of the abuse on me was that I felt isolated from my family. I thought they did not understand me. “Now I have spoken to my mother about the abuse and she supports me and wants the Abbey to apologise to me for what happened,” she said. Meagre compensation With the six women on board, Tracey Emmott of Emmott Snell solicitors led the case against Caldey Abbey. They were seeking acknowledgment, apology, and compensation. Their case maintained that the abbey knew about the offences and failed to report Kotik to police, and that the abbey was liable for alleged assaults committed on property owned by the abbey, as Kotik was charged with the safekeeping and care of the children. Other parents who complained were mentioned in the court documents, but their children were not parties to the case. In a statement of defence seen by the Guardian, the abbey backflipped on its previous admissions and claimed instead it had no knowledge of the alleged sexual abuse, and that there was an “evidential disadvantage” in that none of the monks at the abbey during the time of the allegations were still alive. The defence therefore required the claimants to prove each offence. The abbey also claimed it was not liable as the priest was not employed by the abbey to provide care for children. In addition, the abbey invoked the statute of limitations, claiming the victims were out of time to sue for damages and it was not possible now for the abbey to get a fair trial. The abbey also asked the court to find the claim should not be allowed because the seriousness of the allegations was likely to attract attention that may threaten the continued existence of the abbey. The plaintiffs accepted meagre compensation payments and received no apology. “The defendant tried to avoid their responsibilities by relying on the time limit loophole claiming the abuse happened too long ago and the claims were too late,” Emmott said. “It took the issuing of court proceedings before out of court settlements were offered, and even then my clients’ request for a formal apology as part of the settlement package was never forthcoming.” The Guardian contacted van Santvoort, who remains abbot at Caldey Abbey, for comment, but none has been received. Charlotte feels sure there are still more victims of Kotik and she now wants to find them. She has letters Kotik wrote to her and her sister in the 70s and 80s that hinted at the abuse of her and other children.

She was aware Kotik took groups of children to the dairy where he worked, and to secluded beaches around the island. She is devastated so many children were victimised long after the abbey was aware of the risk Kotik posed to children. ‘The world looks like a new place’ It was not until this year, after the settlement of the case, that Charlotte was at last able to talk openly to her parents about the abuse. She had a continuing fear of being rejected by them, just as Kotik had threatened when she was a little girl. But her determination to expose Kotik’s abuse – and its disastrous effect on her life – has begun a healing process within her family that is slowly restoring her trust and her sense of optimism. “The world looks like a new place, full of promise – and maybe even normality,” she said. “The era of hush, hush and the feeling that people from nice families don’t talk about these things, ends with me.” Do you know more? Contact the author at gearingap@bigpond.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.