|

In Sex Abuse Cases, an Expiration Date Is Often Attached

By Elizabeth A. Harris

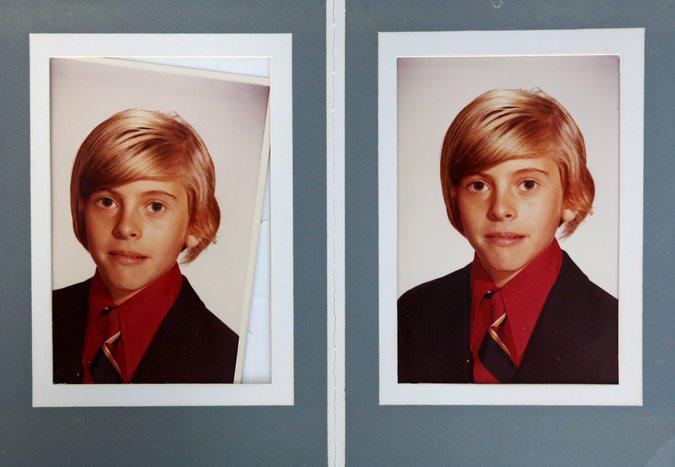

As prep schools increasingly confront past sexual misconduct, they often When John Humphrey was a student at what is now the Pingry School in New Jersey in the early 1970s, he was sexually abused by a teacher, he said. It began when he was 11 years old, and happened several times a week over two school years, until he left the school after the sixth grade. Ray Dackerman said he was abused more than 100 times while he was a student there around the same time, beginning when he was 12 years old. The abuse took place in the teacher’s office and in Boy Scout tents, and even in the teacher’s home while his wife was in the house. Mr. Humphrey and Mr. Dackerman say they were abused by the same man, Thad Alton, at the same school — even in the same tent at the same time. In its own investigation, Pingry found that Mr. Alton had abused at least 27 boys at the school. When the men began settlement discussions with Pingry this fall, the school could have treated them equally, based on their abuse. But instead, their lawyers say, it drew a line using civil statutes of limitation, which spells out how long victims have to bring a lawsuit. In New Jersey, the clock starts running when survivors discover that the abuse left lasting injuries on their lives. They have two years from that date to initiate legal action. Mr. Humphrey, who clearly fell within the statute and so could sue, was most likely looking at a substantial amount of money; Mr. Dackerman, who did not, seemed likely to get far less. Statutes of limitation are devised to protect people and institutions from false allegations that are impossible to defend because evidence is stale, witnesses are dead and documents have been lost. But as schools increasingly confront sexual abuse carried out against children in their care, sometimes decades ago, the statutes have also become a way for them to avoid paying victims. Lawyers, insurers and other experts in the field say that former students whose abuse falls within the statute might receive a settlement in the high six figures, even millions. But once outside it, victims see just a fraction of that, even as schools commission investigations, declare their contrition and promise to do right by them. Often, survivors see nothing at all. That is largely a function of who is paying. Abuse is usually covered by a school’s general liability insurance policy, according to Robb Jones, senior vice president and general counsel for claims management at United Educators Insurance. In general, insurers will pay when the abuse in question is within the statute. “The promise that comes as part of an insurance contract, so to speak, is to pay for legal liability, not for moral liability,” Mr. Jones said. For his company, a significant player among independent schools, paying for a case outside the statute of limitations “would be a true exception.” In those cases, schools have to pay with their own money, bringing their obligations to victims from the past into conflict with the demands of today’s students. “Is it more important to build a new wing for the library for current students, or a new soccer field for current students, or to compensate people who trusted you, and their parents trusted you, and you violated that trust?” said Paul Mones, an attorney who represents victims of sexual abuse. “That is the moral issue, because it boils down to dollars and cents.” Ultimately, schools wrestle with a ghastly question: What kind of value do you place on such a hurt? The first building block of that calculus is whether or not the victim could put the school at the mercy of the courts. Paul G. Lannon Jr., a lawyer at Holland & Knight, which represents many private schools, says that in cases that are outside the statute of limitations, schools are under no legal obligation to pay, but they still sometimes offer substantial amounts. Mr. Lannon said he’d seen more than one claim settle outside the statute for more than $300,000. “I really see that the trend is schools are focused on trying to do the right thing, trying to help survivors heal,” Mr. Lannon said. Stephen Fife was kissed and groomed over the course of two school years by a teacher at Horace Mann School in the Bronx, who once tried to hold him down and rape him. He complained to an administrator at the time, and was told that by pressing the allegation, “you will only tarnish yourself,” he recalled. When he settled with the school about four years ago, he was decades outside the statute, and that was a crucial piece of the negotiations. He said that while the money he received was “beneficial,” it was about a fifth of what he was led to expect by his lawyer. He said the school kept going back to the statute, saying, in effect, “What we’re giving you is from the goodness of our hearts because we don’t have to give you anything.” Horace Mann did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Pingry does not dispute that Mr. Alton preyed on its students. In its report about sexual abuse released in the spring, it said Mr. Alton abused at least 27 students during his tenure there, and that faculty members observed behavior that should have raised alarms. Why did he have students in his office behind a locked door? When adults knocked, why was there a “delay” in answering? The report said that in 1980 Mr. Alton, who left the school at the end of the 1978 school year, pleaded guilty in New Jersey to three counts of private lewdness and three counts of impairing morals of a minor after playing strip poker and masturbating with three 12-year-old boys who were in his fifth grade class at Pingry. He received a suspended sentence and five years of probation. In 1990, he pleaded guilty to second degree sodomy and first degree sexual abuse for incidents involving a 12-year-old boy and a 10-year-old boy. He was sent to prison until 1995. After the school announced it was launching an investigation, 21 of his Pingry victims banded together to make their claims on the school. Represented by the same lawyers, they agreed to give depositions and then sit for mediation with Pingry in an effort to avoid a lawsuit. During his deposition, in a Hyatt hotel conference room in downtown Charlotte, N.C., Mr. Dackerman’s lawyers say one topic seemed to be of particular interest to Pingry: therapy he had received after he and his family were displaced from New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Mr. Dackerman said the abuse wasn’t the focus of his therapy, he was there to talk about his marriage and being out of work. But it did come up. That, his lawyers say, opens him to questions about when he discovered the damage left by his abuse. Rice Fuller was also abused at Pingry, beginning when he was in fifth grade in 1976, in a pattern he described as “so pervasive and so frequent, that when it was happening, it happened everywhere.” Mr. Alton abused him in his car, during Boy Scout trips, at summer camp, and in Mr. Alton’s office at Pingry, behind a heavy wooden door. “I can still hear that door shutting,” Mr. Fuller said. “There were times when people knocked on the door and we would be in there, and he would tell them to go away.” Mr. Fuller is a clinical psychologist, and during graduate school, while working at a psychiatric facility, he decided to see a therapist. Sexual abuse was not the reason he sought therapy, he said, but he discussed it. Mr. Fuller said there was some benefit to getting counseling when he did, but now he feels he’s being punished for it. “They’re going to pick off the people who have a statute of limitations problem, rather than saying we’re committed to doing everything we can to support the people who went through these atrocities — and they used that word in one of their letters, atrocities,” Mr. Fuller said. For each victim, Pingry’s lawyers could spend up to two hours taking their deposition, “and 95 percent of their time was spent on the statute of limitation issue,” said Stephen Crew, one of the lawyers representing the Pingry victims. “If they found somebody who had been to therapy, they’d dig and dig and dig and probe and probe, and it was abundantly clear, crystal clear, that that’s what they were looking for.” At the mediation in September, 19 survivors flew in, at their own expense, from all over the country and gathered around a long wooden conference table in a Manhattan office. One by one, they recounted their stories, in graphic detail, in a room crowded with lawyers, Pingry board members and insurers. Displayed next to the victims were pictures of themselves at the ages they were when the abuse occurred, all big smiles and uneven little boy haircuts, oversized adult teeth still new in their mouths. Mr. Crew said that he and his co-counsel, Peter B. Janci, believe all their clients have at least a “fighting chance” on the statute of limitations. But in mediation, he said: “It became clear that the insurance company was not going to offer much of anything on some cases, and Pingry was not going to make up the difference. That’s where it fell apart.” “I’ve got a set of brothers where one is in and one is out,” he said of Pingry’s interpretation of the statute. “I’ve got plaintiffs who were in the same tent, at the same time, on the same night, with the same perpetrator — one is in, and some are out.” In a statement, Nathaniel Conard, the headmaster of Pingry, said that the school, remained “committed to the ongoing mediation process.” He said that the school recognized the difficulty of the mediation process for survivors. “We remain hopeful we can reach a resolution that helps the survivors heal and move forward,” he said, “while also keeping our school stable and healthy for the students it serves today, and the students it will continue to serve into the future.” Marcy M. McMann, a lawyer for Mr. Alton, declined to comment. The Pingry survivors say they are negotiating as a block, and they refuse to leave any member of their group with nothing. “We’re just entries on a balance sheet,” Mr. Humphrey said. “You’ve reduced my life to a line item on an insurance claim like a roof or a damaged car. If I’m the only guy who gets a settlement, I’ll figure out how to split it between 21 men.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.