Raped at 8 and Forced to Wed at 11, This Woman Tries to End Child Marriage

By Elizabeth Koh

After six years of Johnson’s lobbying, the state Senate voted unanimously Wednesday to ban marriage in Florida to anyone under the age of 18, though a House committee Thursday amended the legislation to allow some minors who are 16 or older and expecting a baby to marry. Johnson says the amended bill is not enough and wants to make Florida the first state to enact a ban on child marriage without exception. “Ms. Johnson has struggled her entire life, and why? Because her parents forced her into a marriage not of her choosing,” said Sen. Lizbeth Benacquisto, R-Fort Myers, who sponsored SB 140, when the bill passed Wednesday. “She is asking for us to change the future for many other young girls.” The first time the bishop raped her, Johnson was too young to have words for what happened. She was 8 and living with her mother in a parsonage in Tampa, attached to the church where her mother’s husband had joined as a pastor. Church leaders had the keys to their place, just four steps from the church building, and her aunt lived in the same house as the bishop nearby. It was in that house, she said, that he first forced Johnson to have sex with him. “I went to school with blood running all down my legs,” she told the Herald/Times. “I didn’t know what was going on, I didn’t know how to take care of myself … It was devastating.”

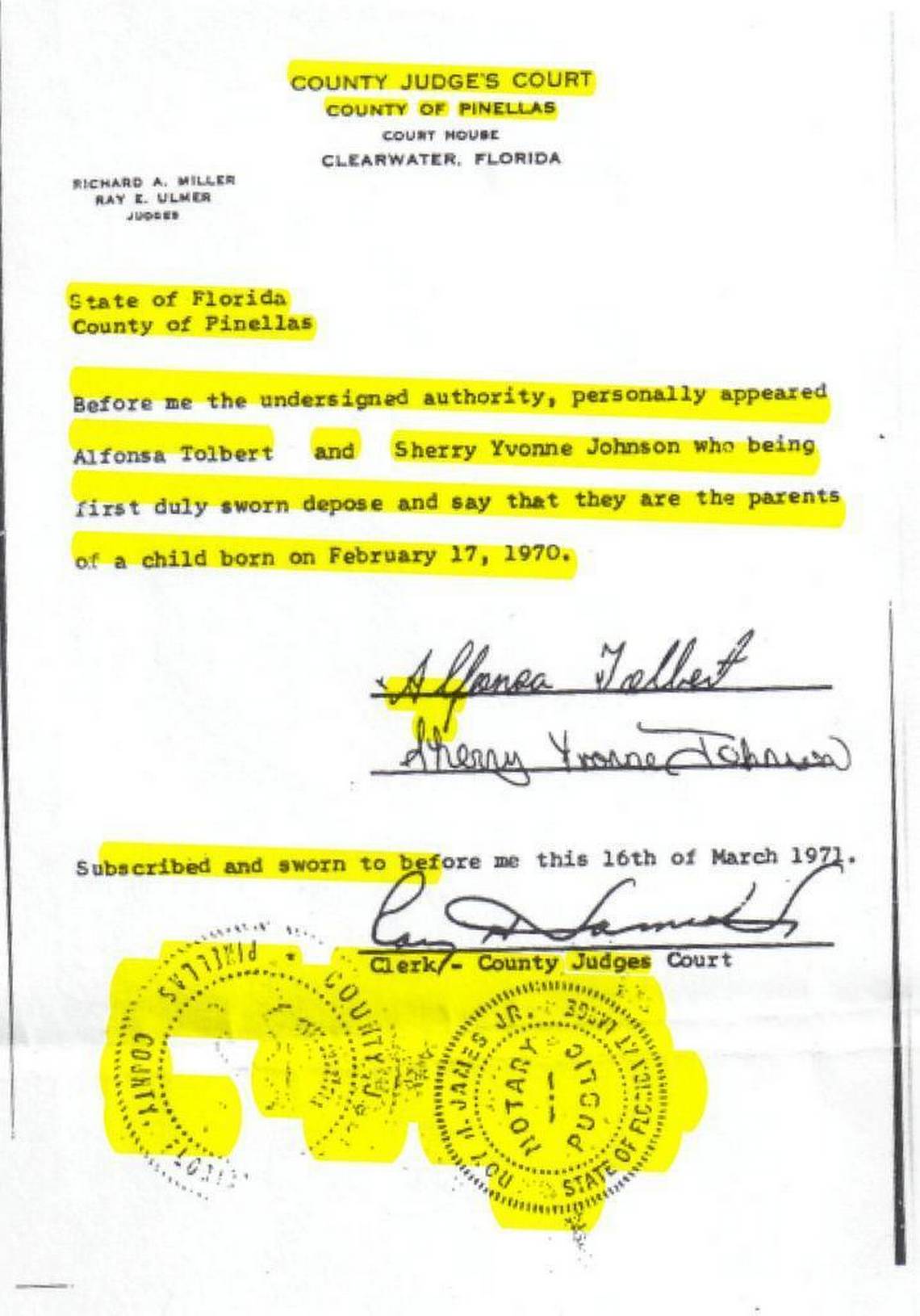

A few days after the assault, she tried to tell her mother what happened, but barely began to describe what had occurred before “she jumped all over me with her words,” she said. “ ‘You’re lying. The bishop doesn’t do anything like that,’ ” she remembered her mother saying. “I felt like I was victimized all over again.” The next time it happened, Johnson said nothing. She also said nothing when her mother’s husband began to rape her, or when a deacon at the church, Alfonsa Tolbert, began to let himself into her room in the parsonage at night. “I thought, ‘I’m gonna get hurt again,’ ” she said. “This is how life is.” It wasn’t until several months later, after she turned 10, that the adults around her were forced to confront what was happening — school officials discovered she was seven months pregnant. It was Tolbert’s child, she said. Johnson remembered being called into a room during the middle of the school day and being examined, then hearing her mother summoned to take her to the hospital. “I didn’t quite understand the word pregnant then,” she said. “I didn’t know where this baby’s going to come from — I was never taught that. Was I going to cough up a baby? As a child, I didn’t have a clue.” Her mother sent her to Miami with the bishop to wait for her baby to be born. When she did give birth at a hospital in February 1971, she remembered lying in the hallway, wracked by contractions, as people walked by and gawked at her like a curiosity.

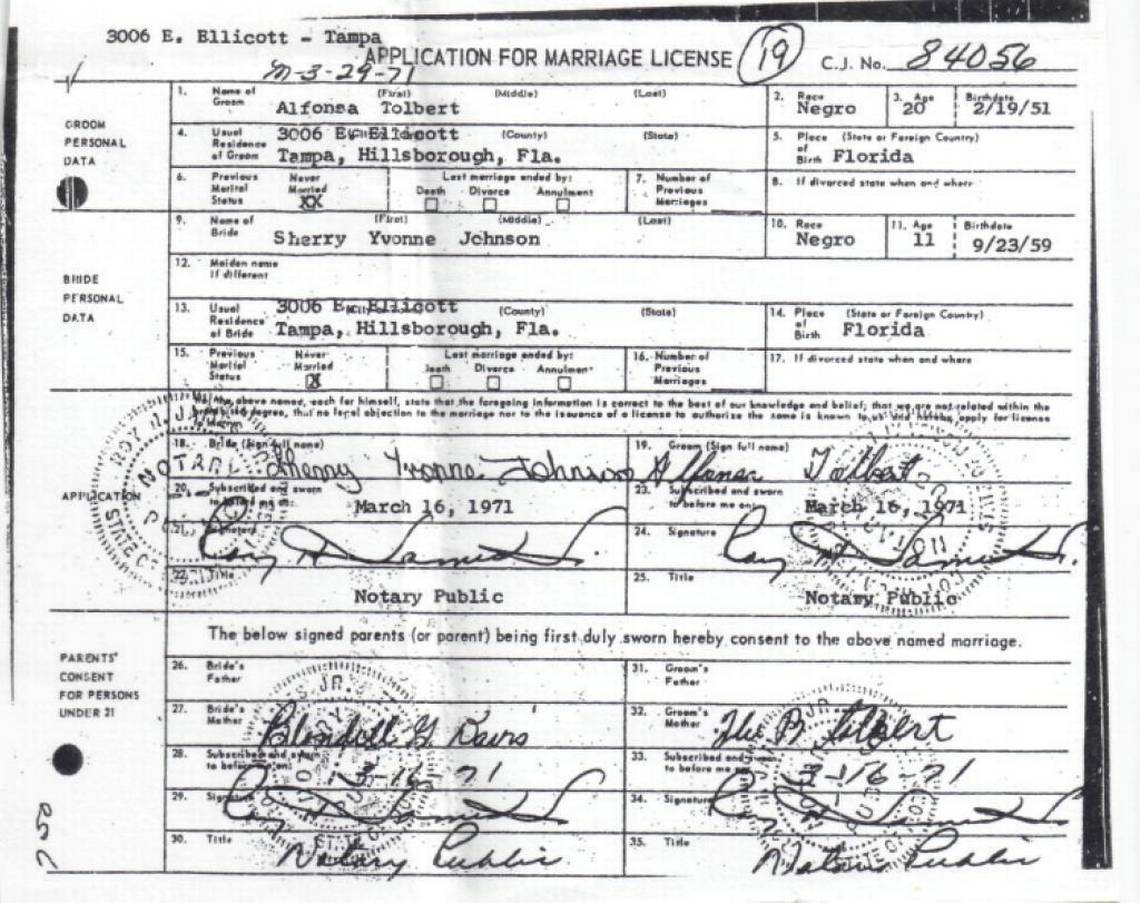

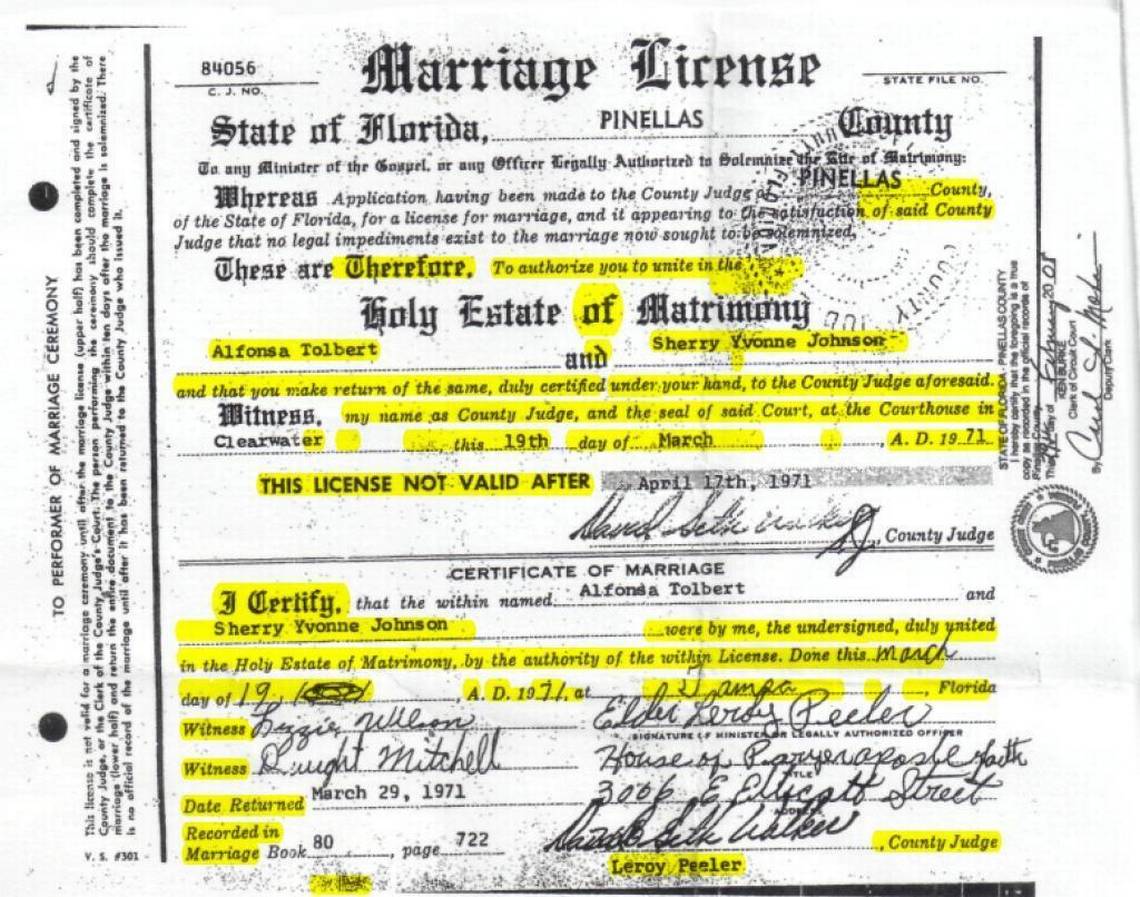

After her daughter was born, Johnson and her baby returned to Tampa, she said, where child welfare workers visited her and asked questions. Not long after, she recounted, her mother took her to a nearby courthouse to be married to Tolbert. Even though Johnson hadn’t even finished fifth grade, marriage at her age was legal. The law in Florida allows minors who are 16 and 17 to marry with their parents’ consent, and also allows county judges to approve marriages with even younger minors if there is a pregnancy involved. The first official they met at the Hillsborough County Courthouse refused to grant a license at all, so Johnson’s mother then took her to Pinellas County, where a judge eventually signed the paperwork, she said. She was married that March to Tolbert, who was 20. She was 11. Her mother made a wedding dress, a veil and a cake. But only two or three other people showed, Johnson remembered. “They didn’t want to be a part of it.” Johnson remained married to Tolbert for six years, and she had five more children, she said. She tried to keep going to school but dropped out around the ninth grade. Tolbert abandoned her often, she added, forcing her to learn to raise her children on her own. “I didn’t have baby dolls to play with — I had real dolls,” she said. “That real doll had to eat, that real doll had dirty diapers, that real doll looked at Mommy … I didn’t know what it was to be a mother.”

Johnson finally obtained a divorce after she turned 17, when she went to legal aid for help and received a $75 check to cover the filing fee, she said. Even after she left Tolbert for good, Johnson said, she struggled. Her next marriage, two years later to a 37-year-old man she met at the same church, became verbally and physically abusive. She bore three more children during that 26-year marriage, and for years continued to attend the same church that her mother went to and in which she had been abused. The bishop who had first raped her died when Johnson was 25. She finally felt free to leave that church, she said: “I felt like shackles fell off my body. I was in bondage, and I felt that I couldn’t be out until he died.” But Johnson continued attending a similarly traditional church while she cared for her nine children, shuttling them from school to sports practice to church and back again. In 2002, she divorced her second husband. Then she moved to Tallahassee in 2008 after marrying once more. She and her third husband ran a restaurant together in the city for a while, but Johnson had her own reasons for relocating to the capital — she had started reflecting on her past and considering what she could do to make sure no one else would go through a similar tragedy. “Who makes the rules? Who makes the laws?” she said. “It pushed me, my passion, to go to legislators, to say, ‘Let’s make a change here.’ ” When Johnson began to talk about her past, writing a book about her ordeal and giving speeches, she learned that she was not alone. According to the advocacy group Unchained at Last, more than 16,000 children have been married in Florida since 2001. Some states have since passed legislation addressing the issue: Texas and Virginia limited marriage to adults last year, though those laws carved out exceptions for emancipated minors. No state has banned marriage involving anyone under the age of 18 outright. In 2012, Johnson began reaching out to legislators in the Capitol, stopping by their offices to leave her business card or writing them to ask if they would consider her idea for a bill. She became familiar with carrying around papers in a black binder and trying to strike up conversations with lawmakers, though “I got a lot of no’s; I got some maybes.” Johnson also became familiar with hearing something else when she told lawmakers she had been married at 11 — that there was no such law allowing children to be married in the state or that Johnson’s case was an anomaly. In 2014, a bill sponsored by Rep. Cynthia Stafford, D-Miami, in the House, which banned marriage under the age of 16, passed the House but died in the Senate. This year’s bill, sponsored by Benacquisto, who chairs the Senate Rules Committee, and Rep. Jeanette Nunez, R-Miami, who serves as speaker pro tempore, has lent more leadership backing to Johnson’s long-proposed bill. When senators unanimously voted to pass the child marriage ban bill Wednesday, Benacquisto praised Johnson as “the reason for the bill” and its voice, and 31 senators agreed in an uncommon procedural move to co-sponsor the bill on the floor in a show of unity. When the bill was passed unanimously with 37 votes, Johnson hugged the people around her, including her 16-year-old granddaughter Danielle Wiggins, who had driven up from Tampa with her mother, Tolonda Tolbert, to be present for the vote. In a House committee meeting the next day, HB 335 passed — but with an amendment preserving an exception for some teens if they have a doctor’s verification of pregnancy and their parents’ consent. Rep. Heather Fitzenhagen, R-Fort Myers, brought forward the change, which would only allow marriage licenses for 16- or 17-year-olds less than two years younger than their partners. “This narrowly tailored exception takes into account real-life situations that occur,” Fitzenhagen said during the meeting, citing some benefits to young couples like insurance benefits, next of kin notification or family leave. The bill now goes to the House, where it will have to compete with the broader Senate bill. Advocates are still hopeful that the latter is the version that will be passed. “All eyes are on Florida right now,” said Johnson’s representative, Ryan Wiggins, citing the importance of setting a national standard and leaving no loopholes to be exploited. Florida law already declares that minors can’t consent, so it is contradictory to say they can agree to be married, she added. Right now, “instead of putting them in jail, we’re legalizing rape.” The law in Florida can also be inconsistently enforced, some victims say: though the law only allows judges to exercise discretion in marrying younger minors if there is a pregnancy involved, some unions fall through the cracks. Delma Rojas was pushed by her parents to marry her 21-year-old boyfriend when she was 14, just months after she and her family emigrated to Fort Lauderdale from Mexico, she said. Rojas, now 40, said her parents insisted she be married because her now ex-husband had sex with her, even though she was not pregnant. When she was wed, in her family’s small apartment by a Notary Public who also baked the wedding cake, the state recognized the license and the consent form her parents signed even though the exception did not apply. She was later granted a divorce. “Just because it’s legal doesn’t make it right,” she said. “It’s still a violation.” Johnson said if the bill passes as amended, she will consider returning to the Legislature to strike it from the law. She is also considering a national push to ban child marriage after it passes in Florida. “It can’t save me — I’m already a survivor,” Johnson said. “I’m just reaching back to help others to not ever have to face it. If it took my life or all of this experience to bring this to a close, then that’s the happiest thing that could ever happen to me.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.