|

Advocates: priest prosecution should empower victims

By Xerxes Wilson

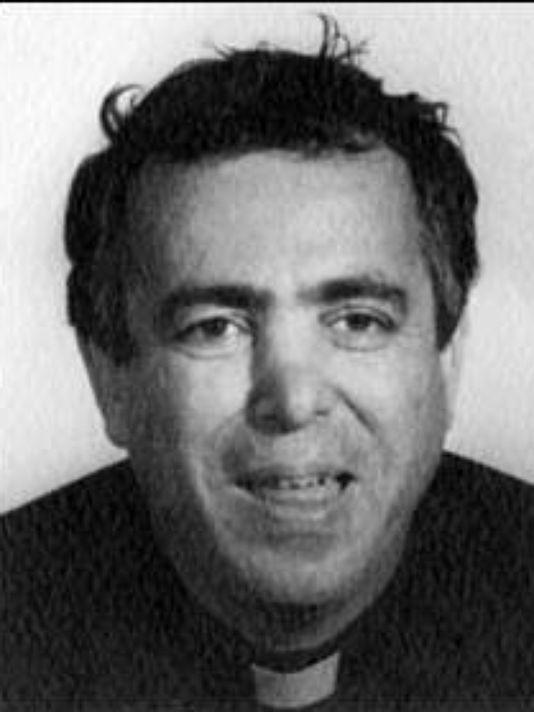

[with video] Sex abuse victims' advocates think the unprecedented indictment of a former Delaware Catholic priest in a decades-old child rape case could embolden more victims to seek justice. John A. Sarro, 76, a former priest with the Catholic Diocese of Wilmington, was indicted last week by a New Castle County grand jury on charges of first-degree unlawful sexual intercourse and second-degree unlawful sexual contact, according to court records. It's a rare instance where prosecution of a sex crime comes decades after the alleged abuse, but the Delaware Supreme Court has upheld similar convictions as recently as 2010. Sarro is accused of fondling and raping a girl who was less than 16 years old between 1991 and 1994 when the abuse allegedly occurred during his time at St. Helena Parish in Bellefonte. He is set to be arraigned later this week and characterized the incident that led to the charges as "an accident" in a brief interview with The News Journal last week. His indictment is the first time the state has brought criminal charges against any of dozens of local priests who were accused of molesting children. Judy Miller heads the Delaware chapter of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, or SNAP, and said the victim's courage to seek prosecution may push others to reach for justice. "This person can be a voice for so many others and look to see if this is an avenue for them," said Miller, who advocated for victims during a wave of civil litigation that ultimately pushed the Catholic Diocese of Wilmington into bankruptcy in 2010. Those lawsuits involved more a dozen priests, some 150 victims and led to a $70 million payout from the diocese, but none of those implicated were criminally prosecuted. The present accusations against Sarro were not part of that litigation. It is not entirely clear why no priest was prosecuted, though the length of time since the abuse occurred and a potential lack of evidence were said to be impediments at the time. Many assumed the statute of limitations on the crime had run out and they could not be prosecuted. Civil litigation was made possible by a special window opened by the Delaware General Assembly that allowed victims to disregard time limitations to sue their abusers. Miller said criminal prosecution was thought to be out of reach. "The idea was that door was not open to them," Miller said. As the number of allegations against local priests grew through the early 2000s, Delaware Department of Justice officials at the time said they would prosecute if evidence and the statute of limitations allowed. When diocese officials in 2006 published a list of 20 priests identified as having credible claims of child abuse against them, half were dead. Sarro was one of the priests identified. Many of the abuse claims were also decades old, The News Journal reported at the time. "It was widely assumed that the statute of limitations had expired or there was not enough evidence to prove a case beyond a reasonable doubt," said Marci Hamilton, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and CEO of CHILD USA, a think tank dedicated to preventing child abuse. Before 1992, a sex crime like rape had to be prosecuted within five years of the crime occurring. That year, the General Assembly removed that constraint and stated that such crimes against children could be prosecuted at any time, as long as that prosecution occurred within two years of being reported to law enforcement. The law was changed in 2002 to remove the two-year constraint. The law has withstood Delaware Supreme Court scrutiny on at least two occasions. Delaware Department of Justice officials declined interview requests about Sarro's case but pointed to a 2010 Supreme Court decision supporting the state's ability to prosecute the case. That decision upheld the conviction of a man found guilty in 2009 of molesting his son between 1988 and 1992. The convicted man appealed his verdict, arguing that the 1992 removal of the five-year statute of limitations did not apply to his crimes because they occurred prior to that law change. The Supreme Court found that the changes to the statute did apply to his case. That's because the five-year limitation in place when the crimes had occurred had not expired by the time the law was changed, according to the court's written opinion. This effectively allowed for prosecution of child sex abuse dating back to 1987. Prosecution of cases where the statute of limitations in place at the time had expired has been found unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, Hamilton said. Nationwide, few priests have been criminally charged relative to the number of abuse claims lodged in civil litigation, she added. "Most victims need decades to come out because of a combination of humiliation and shame," Hamilton said. Valerie Marek is the executive director of Survivors of Abuse in Recovery, or SOAR, a nonprofit that has provided mental health services to victims of sex abuse for the past 25 years. Among her organization's clients, child sex abuse victims wait 20 years on average before reporting the abuse. "Children are overwhelmed and it takes them many years to figure out what happened," Marek said. After the painful process of facing the abuse, criminal prosecution of such cases are rare, Marek said. "Whenever they want to prosecute, it is good news because they are going to save a lot of people that may be abused after that," Marek said. Marek said the current wave of powerful men being outed in news media as sexual predators has empowered victims. "It makes it easier for them with people finally talking about it," Marek said. Hamilton said that empowerment also puts pressure on those in power to act on claims of sexual abuse. "The 'Me Too' movement is now putting pressure on prosecutors, corporations and every organization to hold abusers accountable because they know, eventually, they are going to look bad in the public light," Hamilton said. She added that political pressures against prosecuting priests have waned over the last decade. Miller, the priest-abuse survivors' advocate, said it is a different day. "Victims are being listened to now," Miller said. "That has to empower a lot of people."

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.