Cameras in the courtroom used to be a hot topic. In the nineteen-eighties and early nineties, many states began to allow broad media access to their judicial proceedings, and even the federal courts were experimenting with cameras. Court TV, a network devoted almost exclusively to live coverage of trials, was flourishing. But then the momentum stopped with a thud, and everyone remembers why: the trial of O. J. Simpson.

One can debate, and I have, whether the cameras in Judge Lance Ito’s courtroom during the case, in which Simpson was charged with the murder, in 1994, of his former wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman, affected the conduct of everyone involved and the verdict. (Simpson was acquitted.) Advocates for cameras saw the case as an opportunity for public education about the judicial process; opponents regarded the cameras as accessories to, and a cause of, a demeaning circus. But there is no doubt that the case poisoned the atmosphere for multimedia access to trials. In the two decades since, the trend has been toward fewer cameras, not more. New York is a prime example. The state allowed cameras in its courts for a decade, from 1987 to 1997, but then, post-O. J., forbade them again. (An experiment with expanding access is only now under way.) Court TV died a much mourned death, in 2008. To the extent that the subject of cameras in the courtroom came up at all, the negative example of the Simpson case drowned out much of the debate on the matter.

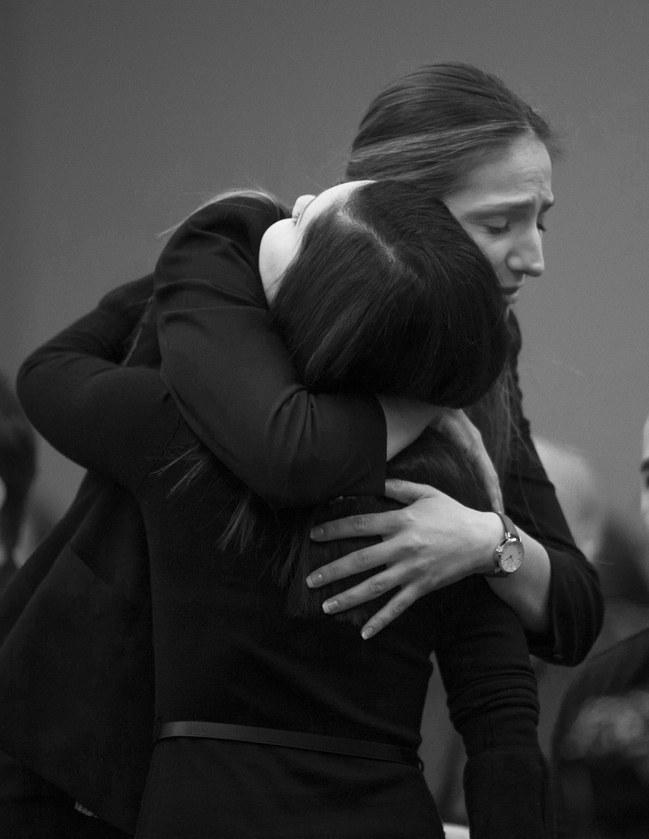

But recent events in Michigan serve as a reminder that cameras can be better than a necessary evil: they can be a positive good. Over the course of several days last month, Judge Rosemarie Aquilina allowed the victims of Lawrence G. Nassar, the former USA Gymnastics and Michigan State University sports-medicine doctor, to recount the stories of the abuse they suffered at his hands. (Michigan gives judges the discretion to allow or prohibit cameras in their courtrooms.)

More than a hundred and fifty victims testified, and their stories were harrowing. Sometimes standing with family members, sometimes alone, the young women told of how Nassar abused the trust they had placed in him and how their lives had been shaped, and often shattered, by what he did to them. Their stories reverberated well beyond the courtroom. As a result of the outrage people around the country expressed, the president of Michigan State University and the entire board of USA Gymnastics were forced to resign. With all respect to the power of the printed (and pixelated) word, this might never have happened if coverage had been limited to the stories produced by the journalists who covered the proceedings. We live in a culture that is saturated with video, from movie theatres to our phones, and we have come to expect to see news events for ourselves. Judge Aquilina did the right thing, and justice was served. (Nassar received multiple sentences, totalling well over a hundred years.)

But cameras are not just an instrument for vindication in the sense of meting out punishment. In 2000, I covered, in person, the trial of the four New York City police officers who were charged with homicide, after firing forty-one shots at Amadou Diallo, an unarmed immigrant, in the Bronx. Even though cameras were at that point generally banned from New York courts, the judge in the case made an exception and allowed Court TV to broadcast it, in part because the trial had been moved to Albany. Judge Joseph Teresi reasoned that, even though he had moved the trial to avoid the pretrial publicity in the Bronx, the people there deserved to see for themselves how the case was going to unfold.

All four officers testified in their own defense, and they were all acquitted. The verdict was debatable but defensible—as anyone who watched the trial could see. The Bronx community reacted unhappily but calmly to the verdict. If there had been no cameras in the courtroom in Albany—if the community had been forced to rely exclusively on reporters like me—it’s possible that the reaction might have been uglier. But cameras allowed everyone to see the trial, in all its complexity, and the response came in an appropriately measured way.

Today, some courtrooms are opening up, especially state and federal appeals courts. The United States Supreme Court remains doggedly, and ludicrously, opposed to cameras, although it eventually releases audio recordings of oral arguments. But the Nassar case reminds us that there is no substitute for seeing justice, or its absence, for ourselves.