Paper Cuts by Stephen Bernard Review – a Powerful Memoir of Sexual Abuse

By Jenny Turner

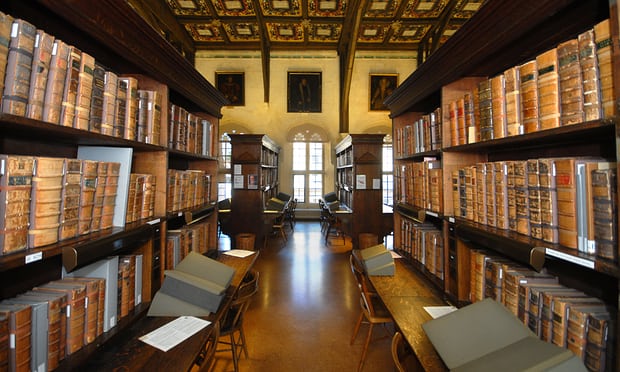

Clerics who abuse don’t commit just physical and emotional violations. The invasion is also spiritual – you’re being forced down and brutalised by the representative of your God on this earth. “Fogarty was ‘in’ me in a physical sense, but he was also ‘in’ me in a psychological sense. There was something full and all-invasive to his violation of me which it is almost impossible not to admire.” Clearly, Bernard’s way of recovering, as best he can, from what was done to him is unusual and, clearly, he’s a singular, self-invented man. A photo on his agent’s website shows him, bequiffed and tweedy, in a punt: but actually, he says, he spoke with “a broad Scouse accent” until he won a scholarship to Sherborne at 15. He’s a huge fan of PG Wodehouse: “His idiolect casts up the promise of an eternal sunshine.” He collects photographic prints of all the colleges of which he’s been a member, his favourites with himself in them, dressed up in his master’s gown, scurrying across the quad. Oxford, for him, has been a “giving place”, a place of care and succour. It’s where he’s met the friends and mentors, doctors and therapists who have helped him gather around himself a decent daily life. The form in which Bernard presents his thoughts, his memories, his perceptions, is liturgical. Moments emerge, dissolve, shape themselves round each other, in rippling patterns of the appalling and the ordinary: “For some years, paper and stickiness and boniness were the only physical sensations I could feel.” The prose is clear and plain, vulnerable in its earnestness, confident in its craft. “I am glad that I wrote it, that it is written,” he writes at the end, and I’m glad too. It’s both a testament of great documentary usefulness and a really beautiful piece of art. • Paper Cuts is published by Jonathan Cape . To order a copy for ?12.74 (RRP ?14.99) go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over ?10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of ?1.99. Since you’re here … … we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too. I appreciate there not being a paywall: it is more democratic for the media to be available for all and not a commodity to be purchased by a few. I’m happy to make a contribution so others with less means still have access to information. Thomasine F-R. If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps fund it, our future would be much more secure.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.