|

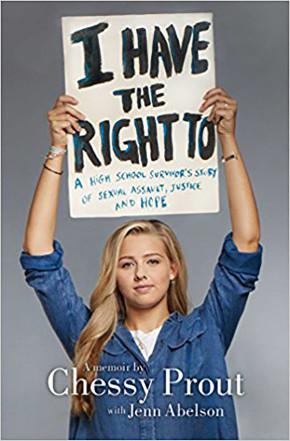

Prep school rape survivor is vindicated in the #MeToo era

By Raquel Laneri

One day in February 2016, Chessy Prout, then 17, picked up an issue of Vanity Fair. The magazine had published a story about her rape case, in which she claimed an 18-year-old senior at her former high school, the elite New England academy St. Paul’s, had sexually assaulted her two years prior. But as she read, Prout grew furious. Her assailant, Owen Labrie — who the previous year was acquitted of felony sexual assault but convicted on three misdemeanor counts of statutory rape and using a computer to lure a minor for sex — was described as a golden boy: handsome, suntanned, captain of the varsity soccer team and “a winner of the headmaster’s award for selfless devotion to school activities” whose Ivy League admission was rescinded after his arrest. Prout, unnamed in the story, felt she was portrayed as a “blank nothing . . . privileged, preppy, naive, impressionable, flummoxed.” “I’m tired of being an anonymous victim while my attacker is this superstar scholar-athlete,” she told her mother. “I want . . . the people who write about me to . . . see I’m a person.” So she decided to come forward and not be an anonymous victim anymore. Now, Prout, 19, has co-written a memoir, “I Have the Right To: A High School Survivor’s Story of Sexual Assault, Justice, and Hope” (Margaret K. McElderry Books, out now). The case was a lightning rod, attracting attention for its sensational details and setting off controversy about the prep-school world of privilege and elitism — especially as some members of the St. Paul’s community felt that their traditions were being threatened. (Alumni of the school include John Kerry and former New York City mayor John Lindsay.) Right now, it’s particularly potent in the #MeToo era, when women — and men — are going public with their tales of harassment and assault. “I am not afraid or ashamed anymore, and I never should have been,” Prout said in her first public interview, on the “Today” show in August 2016. “I feel ready to stand up and own what happened to me and make sure other people, other girls and boys, don’t need to be ashamed, either.” On May 30, 2014, Prout had agreed to go on an outing with Labrie, who promised the younger student a secret view of the campus. She had been warned about the popular athlete; her older sister, a senior, had told Prout to stay away from him, and other female students had described Labrie as “aggressive.” Plus, Prout had heard tales of the school’s “senior salute” tradition, in which upperclassmen (and some women) tried to engage in sexual acts — anything from snuggling to kissing to full-on sex — with as many underclassmen as possible. But after Prout rebuffed his invite, a mutual friend told her that Labrie was a nice guy. “I was flattered that one of the most popular boys thought I was special,” Prout writes. She agreed to meet Labrie two nights before graduation. The date involved sneaking into a locked mechanical room in one of the school’s towers; within minutes, things got sexual. Prout said that Labrie pressed her against the wall and began kissing her and taking off her clothes. He pinned her hands back so she couldn’t move. When she forced her panties back over her hips and asked him to keep all activity above the waist, he called her a tease. “His speed and deftness . . . was astounding and confusing,” she writes. She realized with horror that something was inside her, and that it couldn’t be his fingers, as both his hands were beside her shoulders. “I couldn’t feel my body anymore, so I shut my eyes and focused on the deafening sound of the machines,” Prout writes. “It was so painful but I couldn’t move.” She didn’t want to do anything that would make Labrie angry because “I was scared he could get more aggressive.” Afterward, a shaken Prout told friends what happened, showing them his bite marks on her breasts. She was a virgin who wasn’t entirely sure she had even had sex with Labrie. (Prout writes that, although he texted her that he had put on a condom halfway through their encounter, he later backtracked and said that they hadn’t had intercourse.) It was her dorm adviser who said: “Call your mother. How you handle this will inform the rest of your life.” Prout and her parents — her father is a St. Paul’s alum — pressed charges against Labrie, and he was arrested that summer. Harvard, learning of the investigation, rescinded his acceptance. “All I really wanted was for Owen to acknowledge what he’d done,” writes Prout, whose family hoped to hammer out a plea deal with Labrie’s lawyer. “And I needed everyone else — especially the kids at school — to know the truth.” When Prout arrived on campus for the fall semester of her sophomore year, she found she was persona non grata at St. Paul’s. Her volleyball teammates wouldn’t look at her. The hockey players, who ruled the school, would follow her and stare her down. She began eating meals in her room, subsisting on Luna Bars and tangerines, for fear of walking to the dining hall alone. When she heard from one of her few remaining friends that her classmates were calling her a liar and spreading rumors about her, she was particularly heartbroken. “These were the girls who’d seen me moments after my assault . . . and who, I’d later learn, told the police that I was shaking in shock,” she writes. “But none of it mattered when I became a liability and threatened their rise to the top of the social stratosphere at St. Paul’s.” Juliet Williams, a gender studies professor at UCLA who has written books about gender and education, told The Post that boarding-school “traditions and values date back to a time of unapologetic racism, sexism, classism and nationalism.” After being violated, Prout says that other girls came to her with their own tales of sexual assault at the school. However, she was the only one to press charges. The environment was so toxic that near the end of the first semester since the assault, a couple of senior boys made an announcement during chapel about a Powder Puff football game, adding that only girls above the age of consent could participate. The room erupted in laughter; some of the teachers chuckled, too. This was after Labrie had fired his lawyers and the plea deal was off. Prout felt it was a personal attack. “This environment is not supportive or respectful to girls,” Prout told her counselor that afternoon, announcing that she wanted to return home to Naples, Fla. “I’m reminded of the assault every day.” The case finally went to trial in August 2015. Labrie was convicted on five out of nine counts. One of those included using a computer to lure a minor for sex, a felony that required him to register as a sex offender. Although Labrie would eventually have to go to jail, he would remain free on bail while his lawyers appealed. The case got a lot of attention. Consent and sexual assault on college campuses had become a major issue, and people — particularly women — were beginning to question certain sexist traditions at universities. It made the Labrie case particularly scandalous that those involved were in high school. Furthermore, Labrie was the first person at St. Paul’s to be accused of rape because of “senior scoring” — a tradition that, according to Vanity Fair, the school was well aware of, as it had repeatedly painted over a “scoring wall” which kept track of senior hookups for years. In fact, many St. Paul’s alumni and students felt that it was unfair that the young man, who was basically engaging in the same activities as many of his classmates, would have to give up his Harvard education because of his actions. One prominent parent had sent a letter to other alumni and parents asking them to join him in pledging money to get Labrie a high-powered lawyer. In a statement to The Post, Labrie’s legal team wrote: “Owen Labrie was acquitted of all charges alleging that he had engaged in forceful or nonconsensual sexual assault . . . Mr. Labrie remains confident that his appeals currently pending before the New Hampshire Supreme Court will be successful and that he will receive a new trial . . . and be acquitted of all charges upon retrial.” Prout, meanwhile, was having nightmares and had taken to hitting herself. Her name had been leaked to the press during her trial, and online trolls published photos of her in a bikini along with her home address and the names of her two sisters. Her dad even lost his job for a while because of all the time he took off to support her. “Rape . . . affects more than just the victims,” writes Prout. “It hurts everyone who loves them.” Her ordeal may help lead to change, however. Professor Williams noted that, in the age of #MeToo, “The cult of silence and the privilege of protection that has been absolutely essential to the perpetuation of [traditional boarding-school attitudes] is being challenged.” After going public with her “Today” interview a year and a half ago, Prout has learned to view herself as a “survivor” rather than a “victim.” She has launched a nonprofit, called #IHaveTheRightTo, and by her senior year, had excelled on her new Florida school’s mock-trial team, starred in the annual musical and had a boyfriend. After taking a year off, she plans to go to Barnard in the fall of 2018. “Maybe I’ll be a lawyer. Maybe I’ll be a politician, a producer, a writer. Maybe I’ll be an activist,” she writes. “I have the right to live my life fearlessly.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.