|

Hundreds of Missouri’s 15-year-old brides may have married their rapists

By Eric Adler

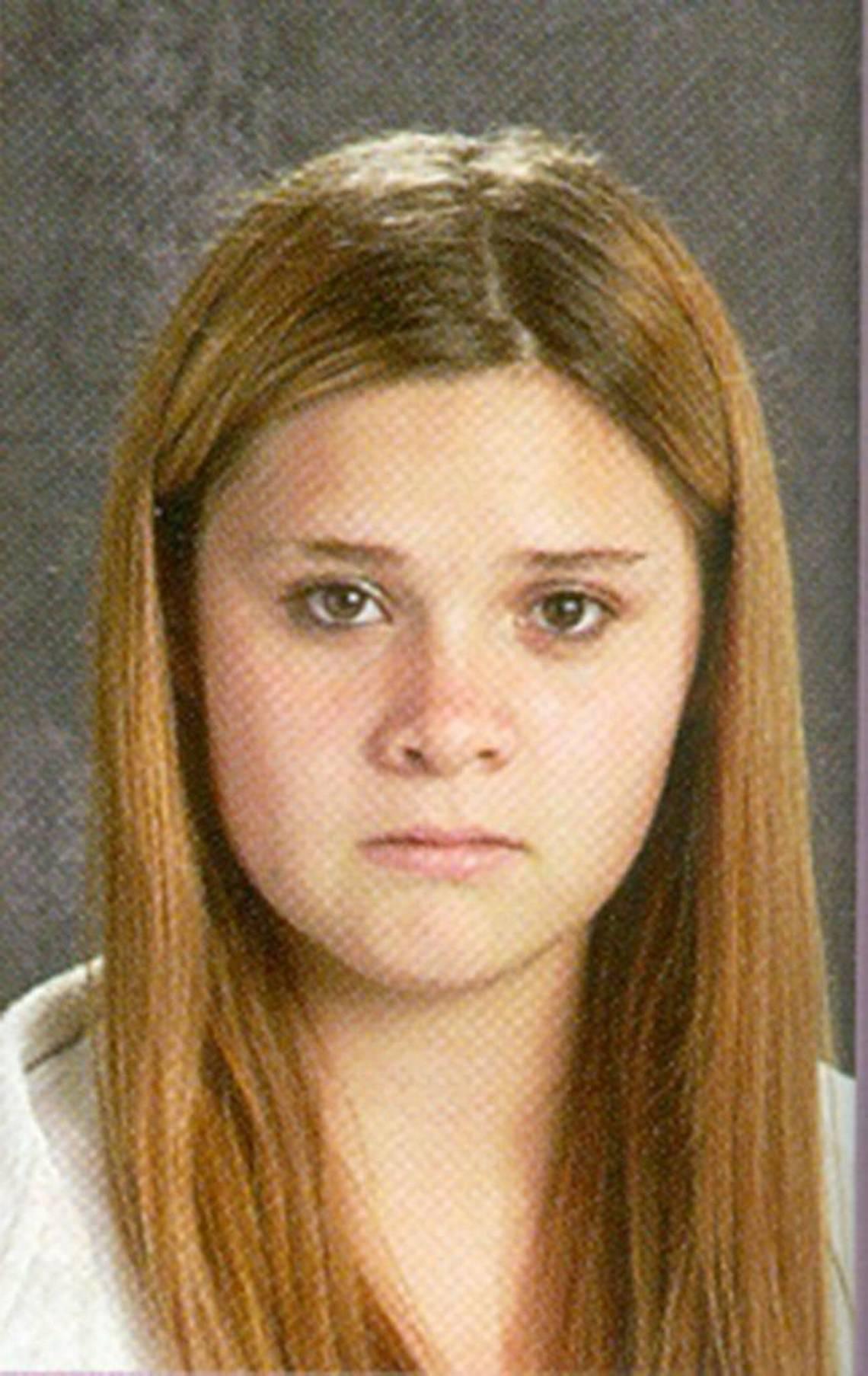

[with video] District Court Judge Gregory W. Moeller peered down from the bench, aghast. “I was horrified by the case,” the Idaho judge recalled recently. In front of him, ready for sentencing, Keith Strawn — a father, 6-foot-3 with black-framed glasses the color of his boyish haircut — stood sad and penitent. Strawn thought he had been doing right by his 15-year-old daughter, Heather, only to realize too late what a massive mistake he had made bringing her to Missouri — the easiest place in America for a 15-year-old to wed. “I love my daughter very much and never would I do anything to intentionally harm her or put her in harm’s way,” Strawn implored the judge at his May 2016 sentencing inside Idaho’s Fremont County Courthouse. “At the time I thought I was making the right decision, but after looking back I realize that that was the wrong decision, and I regretfully made that decision in duress.” But the judge was having none of it. The facts of the case were clear. Heather Strawn was 14 years old when she became pregnant by her then 24-year-old boyfriend, Aaron Seaton, who had plied her with alcohol before having sex with her inside his camper parked next to the I-I Fly shop in Ashton, Idaho. Across the nation, that is statutory rape. But Heather insisted that she cared for Seaton. So, instead of turning the young man in to police, Strawn, in August 2015, packed the family into his car. On the day of Heather’s 15th birthday, when she was nine weeks pregnant, they drove through the night, 17 hours and more than 1,100 miles, to Kansas City to marry her off. That way, the baby would be born within wedlock. And the police, Strawn thought, would be kept at bay. In Idaho, the couple would have had to go before a judge to be married, risking arrest. But in Missouri no judge is needed. All that is necessary is the signature of one parent. From 1999 to 2015, more than 1,000 15-year-olds married in Missouri. Of those, The Star’s review of data shows, more than 300 married men age 21 or older, with some in their 30s, 40s and 50s. Assuming they had premarital sex, those grooms would be considered rapists. The definitions of statutory rape and other child sex crimes vary from state to state. Missouri defines statutory rape as anyone 21 or older having sex with someone under 17 outside of marriage. Within marriage, sex with a minor is legal. But not before. The number of possible offenders from out of state grows even higher when taking into account other states’ stricter laws, some of which prohibit older teens from having sex with younger teens. Back in her home state of Utah, Strawn’s ex-wife — Heather’s mother —was livid to find out about the marriage. Under Missouri law, her objections didn’t matter. She alerted Idaho police. Heather’s father and new husband were soon arrested. By the time their trials commenced, the marriage had been annulled and Heather had lost her baby to a miscarriage. “At the time, I really didn’t think much of the age difference,” Seaton declared to Judge Moeller at his sentencing. In April 2016, he received 15 years in prison and was forced to register as a sex offender. “Everything I’ve put her family through, and her through, my family through,” he said, “I would like to apologize for that, for this whole mess. I’m deeply sorry.” One month later, it was Heather’s father’s turn. His sentence: four years for felony injury of a child. Part of that injury included hauling Heather to Missouri to marry. But because his daughter was somewhat willing and Strawn didn’t actually force her into marriage, the sentence was suspended. The judge castigated Strawn for his “abysmally poor parental judgment.” “Your daughter needed a parent. Instead she had an enabler,” Moeller intoned. “You were supposed to be the one with the better judgment and you completely failed in that regard.” Strawn was sentenced to 120 days in jail for his role in promoting “a vile farce of a marriage.” “Perhaps as you spend each of those 120 days in jail,” Moeller said, “you will think about the 120 days your daughter was married to a rapist because of you.” ‘I guess’At 21, Jeremie Rook knew he was in violation of Iowa’s statutory rape law when he traveled to Platte County, Mo., to marry Brittany Koerselman, 15 and seven months pregnant. But once married, the threat of prison vanished, even though, technically, he still committed the act. “Yeah, they left us alone,” Brittany said of the police. “I never heard back from them at all.” Ashley Duncan also married because she thought she was saving a boyfriend from prison. If only she’d had a judge to guide her, she might have been saved from a disastrous marriage. She was a kid of 15, a high school freshman in the Bootheel’s Pemiscot County. Queasy from morning sickness, her stomach lurched as she climbed on the bus after school that February day in 2009. Two weeks earlier, in the midst of a record January ice storm that cracked branches like brittle bones, she’d discovered she was more than a month pregnant by her 18-year-old boyfriend. Her aunt’s voice pealed down the aisle. “Ashley, come on, get off the bus,” she recalled Christy Cothran, her guardian, shouting. “You’re getting married today.” Clad in school clothes and hauling her book bag, Ashley scooted along her seat near the window. The date was Friday the 13th. She could feel the eyes of other students on her. She heard a few muttering. “You’re getting married?” they questioned. “You’re too young.” She said nothing, but she knew in her heart that they were right. She felt afraid as she ambled back up the aisle, out of the bus and into her aunt’s car. “They wanted me to get married,” Ashley, now 24 and the mother of four, said. “I knew I shouldn’t have been making that decision that young. It was just something they told me that, like, I had to do or my child’s father would go to jail.” Ashley, indeed, said the precise intent was to keep her boyfriend from being charged with statutory rape. It was only recently that Ashley was surprised to discover everyone was wrong. Laws differ from state to state, but in Missouri, statutory rape does not generally apply to an 18-year-old having sex with a 15-year-old. It is defined as sex between anyone age 21 or older with someone under age 17. Had there been a judge to explain the law, she still would have had her baby, while avoiding the painful marriage. Ashley stood rattled and uncertain as she took her vows. She vividly remembers the pastor they hastily found to perform the ceremony asking her if she took her boyfriend to be her lawfully wedded husband. “I said, ‘I guess,’” Ashley recalled. Her sister, standing nearby, chided her, “You’re supposed to say, ‘I do.’” After the ceremony, the family got back in the car. It was a school day. They drove Ashley’s younger sister to her volleyball practice. No presents. Later, back home in Steele, Mo., they shared a cake. “I threw cake in his face. He threw cake in my face. Then his niece ended up getting the whole cake and throwing it in the laundry basket,” Ashley said. “And that’s pretty much how my wedding day was.” It’s not that Ashley, whose maiden name was Tidwell, didn’t like Daniel Duncan, an upperclassman, built small and slender. They met on the school bus. “The first thing I noticed about him is that he was very quiet,” Ashley recalled. “He was quiet to everybody but me. He didn’t show much attention to anyone else.” It made her feel special. Two months after they began dating, they briefly broke up. When they got back together, that was that. “I think I thought I loved him,” Ashley said. “I know now that’s not what it was.” How Daniel feels about it all is unclear. The couple, still legally married, stayed together for about two years but have been separated now for more than six. Ashley said he periodically visits the two children they share, but his appearances can’t be predicted. Repeated attempts by The Star to reach Daniel through Facebook, messages through a friend and relatives, at his workplace and by certified mail received no response. If Ashley had it to do over again, “I would not get married,” she said. She would still have had her children, certainly. Daniel Jr., called D.J, now 8, was born seven months after her wedding. Her greatest regret: dropping out of school her freshman year, when she was six months pregnant. She once hoped to graduate and go on to become a nurse. “It was getting hard for me at school,” she said. “I was getting bullied because I was married, I was pregnant, it was getting confusing to the teachers.” But the real problems, Ashley claimed, began in 2014, soon after their second son, Colby, was born. Noxious and even violent arguments broke out in front of their children. By the end of that year, she and the boys were gone. “What made me leave him is what his (Daniel’s) dad said to me,” Ashley recalled, “He said, ‘If you seen somebody doing this to your family, like your sister, would you stop it? Would you tell her to get out of the relationship?’ And I said, ‘No, I would stop it.’ He said, ‘Then why are you allowing it to happen to you?’ That is the day I left, and I never went back.” Romeo and JulietThere is no easy answer for how law enforcement should act in the face of young girls who marry the men who could be their rapists. Do they arrest and prosecute? What if the bride and family aren’t complaining? Enforcing criminal law is not the role of the county recorder of deeds. “We cannot do anything, legally,” said Gloria Boyer, who for 27 years has issued licenses at the Platte County Courthouse, where Brittany Koerselman was married. “If a parent signs and a couple wants to get married, there is nothing we can do to stop issuing that marriage license. … “You see situations come through where you’re not necessarily really comfortable with it. You know, I’m the recorder. I’m not the police for this.” Modern statutory rape laws grew out of a centuries-old English legal doctrine called parens patriae, explained Michelle Oberman, a professor and expert on statutory rape law at the Santa Clara University School of Law in California. The Latin term means “parent of one’s country,” and speaks to the notion of the government as parent, creating laws or steps to protect citizens who are either too vulnerable or young to protect themselves. Depending on the issue or state, those laws can range all over: 16 to drive; 17 in Missouri to have sex out of wedlock, but if you’re one day younger and the partner is 21 or older then it’s statutory rape; 21 to drink, although it used to be 18. Lawmakers now debate how young is too young to buy firearms. “The reason why the issue of child marriage is so interesting is that it really forces us to think of what decisions kids are capable of making on their own, and what decisions they actually need to be protected from because they are too young and too vulnerable and they get it wrong,” Oberman said. Overlapping that, she said, is the matter of prosecutorial discretion, deciding which cases are worth pursuing. Overall, statutory rape cases come in three varieties, said Leslie Garfield Tenzer, a law professor at Pace University in New York: “There are the sick cases,” she said, “the teacher sleeping with the child, or the 29-year-old sleeping with the child. That’s an easy case. “Then you have the case in which the parent alerts the authorities and pushes for it. The parent is irate.” Those, too, tend to get prosecuted, she said. But the third and thornier type is one in which the law has clearly been broken, but neither the child, partner nor parents are complaining. “When you have a crime,” Tenzer said, “basically you’re saying that the defendant wronged society. Convicting someone gives the family of the victim some sense of retribution, it maybe rehabilitates the defendant and it is a deterrence to society: Don’t do this. “But if you have this girl who’s in love with this guy, we really don’t need to rehabilitate them. We don’t necessarily need retribution if the parents understand that there’s love there. And the question is, ‘Do we want to take the time of prosecutors and taxpayers’ money for a case to basically send a message to the rest of the world?’” In Idaho, the judge sent exactly that message. Heather Strawn’s marriage to Aaron meant nothing. She was 14 when she became pregnant. Police acted as soon as they received a complaint from her mother. (The Strawns and Aaron Seaton declined interviews or did not return The Star’s inquiries.) In Brittany Koerselman’s native Iowa, Chief Deputy Jerry Birkey of the Lyon County Sheriff’s Department said that if evidence of statutory rape exists, his office will make an arrest, even if the victims object. “A lot of times it doesn’t matter if they don’t cooperate, we’ll still go forward,” he said. Birkey, in fact, said that in Brittany’s case, his office knew it could prove a case against Jeremie with DNA as soon as their baby was born. But the county attorney did not want to pursue it. “Our county attorney hates these cases,” Birkey said. “We call them Romeo and Juliet cases, because really there is no winner. The victim ends up mad at you because they feel they’re in love. “But if you ask any of our officers if charges should be filed, they’re going to say yes.” Shayne Mayer, the Lyon County attorney, said she could not discuss specific cases. “In general,” she said, “I don’t think these are easy cases from the sense of what end are we trying to gain here? Do you have an angry parent? Do you have a girl who is being taken advantage of? Obviously, I understand that it’s illegal. What do we possibly gain from a prosecution of this individual? Are we going to incarcerate the father of her baby, and then who’s going to pay for the child?” Mayer said the decision to prosecute would consider factors such as abuse, coercion and family complaints that might force them to charge and prosecute. “But are you going to put this guy on the sex offender registry for the rest of his life?” she said. “I mean those are the consequences that flow from this type of case.” It’s also possible that statutory rapists heading to the altar to escape the police are not arrested because law enforcement never learns of them. Statewide, the number of 15-year-olds marrying has dwindled each year, from 104 in 1999 to 16 in 2015. Missouri’s Jackson County has recorded 64 marriages of 15-year-olds since 1999, more than any of the other 113 Missouri counties. But more recently in the county, the numbers have dropped to one, two or three such marriages a year. “I suspect we don’t see a lot of these cases possibly because they are not being reported to police and, thus, not being submitted to our office,” said Mike Mansur, spokesman for Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker. “If we were aware of a case or if one were submitted, we would consider filing charges.” Even then, Mansur added, “we would need to weigh the victim and her family’s wishes. This is not to say that would be the only factor or the major factor, but it would need to be considered.” Eight years after saying “I guess,” Ashley is happier now, in a loving relationship with Tim Donnor, a pipe fitter, who considers all of Ashley’s kids his own. They have two more, Bentley, 5, and Tim, 4. As soon as Ashley can afford a divorce, the couple hope to wed. Ashley said she supports any law that would raise the minimum marriage age to 18. She has long realized that the only reason she got married so young was out of fear and obedience, neither of them good reasons. “It was a little bit of both,” she said. “I didn’t want my child’s father to go to jail. I really thought that he loved me. “I think I would have believed anyone who had said they loved me at 15.” Contact: eadler@kcstar.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.