|

Pope Francis Is Beloved. His Papacy Might Be a Disaster.

By Ross Douthat

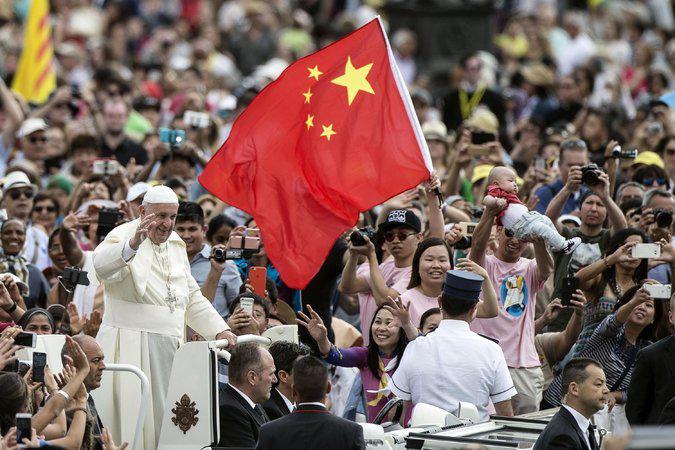

The conversation has become predictable. A friendly acquaintance — a neighbor, a fellow parent, our real estate agent — asks about my work. I say I’ve been writing a book about the pope, and the acquaintance smiles and nods and says “Isn’t he so wonderful?” or, “That must be an inspiring thing,” or, “I have a friend who would love to read it.” And then eventually I find myself saying, uncomfortably, “Well, they should know that it’s not entirely favorable.” A pause, puzzled and slightly crestfallen. “But you’re writing about the nice pope?” The consistency of these exchanges is a testament to the great achievement of Pope Francis’ five years on the papal throne. He leads a church that spent the prior decade embroiled in a grisly sex abuse scandal, occupies an office often regarded as a medieval relic, and operates in a media environment in which traditional religion generally, and Roman Catholicism especially, are often covered with a mix of cluelessness and malice. And yet in a remarkably short amount of time — from the first days after his election, really — the former Jorge Bergoglio has made his pontificate a vessel for religious hopes that many of his admirers didn’t realize or remember that they had. Some of this admiration reflects the specific controversies he’s stirred within the church, the theological risks he’s taken in pushing for changes that liberal Westerners tend to assume Catholicism must eventually accept — shifts on sexual morality above all, plus a general liberalization in the hierarchy and the church. But when people say, “He makes me want to believe again,” as a lapsed-Catholic journalist said to me during one of these awkward “What do you have against Pope Francis?” conversations, they aren’t usually paying close attention to the battles between cardinals and theologians over whether his agenda is farsighted or potentially heretical. Nor are they focused on his governance of the Vatican, where Francis is a reformer without major reforms, and the promised cleanup may never actually materialize. What my friends and acquaintances respond to from this pope, rather, is the iconography of his papacy — the vivid images of humility and Christian love he has created, from the foot-washing of prisoners to the embrace of the disfigured to the children toddling up to him in public events. Like his namesake of Assisi, the present pope has a great gift for gestures that offer a public imitatio Christi, an imitation of Christ. And the response from so many otherwise jaded observers is a sign of how much appeal there might yet be in Catholic Christianity, if it found a way to slip the knots that the modern world has tied around its message. To be a critic of such a pope, then, is to occupy something like the position of George Orwell, who opened an essay on Mohandas Gandhi with the aphorism, “Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent.” Except that the pope’s most serious critics are not skeptics like Orwell who don’t actually believe in saints: They are faithful Catholics, for whom criticism of a pontiff is somewhat like the criticism of a father by his son. Which means they — we — are always at risk of finding in the mirror the self-righteous elder brother in Jesus’ parable of the prodigal son, who resents his father’s liberality, the welcome given to the younger brother coming home at last. But it’s still a risk that needs to be taken — because to avoid criticizing Francis is to slight this pope’s importance, to fail to do justice to the breadth of his ambitions and purposes, his real historical significance, his clear position as the most important religious figure of our age. Those ambitions and purposes are not the ones for which he was elected. The cardinals who chose Jorge Bergoglio envisioned him as the austere outsider. But that kind of revolution hasn’t really happened. Vatican life is more unsettled than under Benedict XVI, the threat of firings or purges ever present, the power of certain offices reduced, the likelihood of a papal tongue-lashing increased. But the blueprints for reorganization have been put off; many ecclesial princes have found more power under Francis; and even the pope’s admirers joke about the “next year, next year …” attitude that informs discussions of reform. Meanwhile, the pope’s response to the sex abuse scandal, initially energetic, now seems compromised by his own partiality and by corruption among his intimates. The last few months have been particularly ugly: Francis just spent a recent visit to Chile vehemently defending a bishop accused of turning a blind eye to sex abuse, while one of his chief advisers, the Honduran Cardinal Óscar Maradiaga, is accused of protecting a bishop charged with abusing seminarians even as the cardinal himself faces accusations of financial chicanery. So the idea of this pope as a “great reformer,” to borrow the title of the English journalist Austen Ivereigh’s fine 2014 biography, can’t really be justified by any kind of Roman housekeeping. Instead Francis’ reforming energies have been directed elsewhere, toward two dramatic truces that would radically reshape the church’s relationship with the great powers of the modern world. The first truce this pope seeks is in the culture war that everyone in Western society knows well — the conflict between the church’s moral teachings and the way that we live now, the struggle over whether the sexual ethics of the New Testament need to be revised or abandoned in the face of post-sexual revolution realities. The papal plan for a truce is either ingenious or deceptive, depending on your point of view. Instead of formally changing the church’s teaching on divorce and remarriage, same-sex marriage, euthanasia — changes that are officially impossible, beyond the powers of his office — the Vatican under Francis is making a twofold move. First, a distinction is being drawn between doctrine and pastoral practice that claims that merely pastoral change can leave doctrinal truth untouched. So a remarried Catholic might take communion without having his first union declared null, a Catholic planning assisted suicide might still receive last rites beforehand, and perhaps eventually a gay Catholic can have her same-sex union blessed — and yet supposedly none of this changes the church’s teaching that marriage is indissoluble and suicide a mortal sin and same-sex wedlock an impossibility, so long as it’s always treated as an exception rather than a rule. At the same time, Francis has allowed a tacit decentralization of doctrinal authority, in which different countries and dioceses can take different approaches to controversial questions. So in Germany, where the church is rich and sterile and half-secularized, the Francis era has offered a permission slip to proceed with various liberalizing moves, from communion for the remarried to intercommunion with Protestants — while across the Oder in Poland the bishops are proceeding as if John Paul II still sits upon the papal throne and his teaching is still fully in effect. The church’s approach to assisted suicide is traditional if you listen to the bishops of Western Canada, flexible and accommodating if you heed the bishops in Canada’s Maritime Provinces. In the United States, Francis’ appointees in Chicago and San Diego are taking the lead in promoting a “new paradigm” on sex and marriage, while more conservative archbishops from Philadelphia to Portland, Ore., are sticking with the old one. And so on. These geographical divisions predate Francis, but unlike his predecessors he has blessed them, encouraged them and enabled would-be liberalizers to develop their ambitions further. In effect he is experimenting with a much more Anglican model for how the Catholic Church might operate — in which the church’s traditional teachings are available for use but not required, and different dioceses and different countries may gradually develop away from each other theologically and otherwise. This experiment is the most important effort of his pontificate, but in the last year he has added a second one, seeking a truce not with a culture but with a regime: the Communist government in China. Francis wants a compromise with Beijing that would reconcile China’s underground Catholic Church, loyal to Rome, with the Communist-dominated “patriotic” Catholic Church. Such a reconciliation, if accomplished, would require the church to explicitly cede a share of its authority to appoint bishops to the Politburo — a concession familiar from medieval church-state tangles, but something the modern church has tried to leave behind. A truce with Beijing would differ from the truce with the sexual revolution in that no specific doctrinal issue is at stake, and no one doubts that the pope has authority to conclude a concordat with a heretofore hostile and persecuting regime. Indeed, he is building on diplomatic efforts by his predecessors, though both of them declined to take the fraught step to a formal deal. But the two truces are similar in that both would accelerate Catholicism’s transformation into a confederation of national churches — liberal and semi-Protestantized in northern Europe, conservative in sub-Saharan Africa, Communist-supervised in China. They are similar in that both treat the concerns of many faithful Catholics — conservative believers in the West, underground churchgoers in China — as roadblocks to the pope’s grand strategy. They are similar in that both have raised the specter of schism by pitting cardinals against cardinals and sometimes against the pope himself. Above all, the two truces are similar in that they both risk a great deal — in one case, the consistency of Catholic doctrine and its fidelity to Jesus; in another, the clarity of Catholic witness for human dignity — for the sake of reconciling the church with earthly powers. And they take this risk at a time when neither Chinese Communism nor Western liberalism seem exactly like confident, resilient models for the human future — the former sliding back toward totalitarianism, the latter anxious and decadent and beset by populist revolts. Which means that if these two bets go badly the Francis legacy will be judged harshly — in spite of his charisma, his effect on secular observers, and all the other elements of the “Francis effect.” The risks of the Chinese gamble are already apparent in the weirdly sycophantic language that Francis’ allies have used toward the Communist regime, and their eagerness to reassure Beijing that unlike, say, American evangelicals, Rome would never take the threatening step of mixing religion and politics. If current trends continue, China could have one of the world’s largest Christian populations by this century’s end, and this population is already heavily evangelical; indeed, the Vatican’s desire for a deal with Beijing is influenced by the fact that a divided Chinese Catholicism is being outcompeted for converts. But if that deal permanently links the Roman church with a corrupt and fated regime, Francis will have ceded the moral authority earned by persecuted generations, and ceded the Chinese future to those Christian churches, evangelical especially, that are less eager to flatter and cajole their persecutors. The gamble on an Anglican approach to faith and morals is even more high-risk — as Anglicanism’s own schisms well attest. The pope’s “new paradigm” has defused the immediate threat of schism by maintaining a studious ambiguity whenever challenged. But it will ensure that the church’s factions, already polarized and feuding, grow ever more apart. And it implies a rupture (or, if you favor it, a breakthrough) in the church’s understanding of how its teachings can and cannot change — one less dramatic in immediate effect than the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, but ultimately more far-reaching in its implications for Catholicism. Francis’ inner circle is convinced that such a revolution is what the Holy Spirit wants — that the attempts by John Paul II and Benedict to maintain continuity between the church before and after Vatican II ended up choking off renewal. They are right that the John Paul II paradigm was fraught with flaws and tensions; the ease with which Francis has reopened debates that conservatives considered closed has testified to that. But this pope has not just exposed tensions; he has heightened them, encouraging sweeping ambitions among his allies and pushing disillusioned conservatives toward traditionalism. Like certain imprudent medieval popes, Francis has pressed papal authority to its limits — theological this time, not temporal, but no less dangerous for that. All of this makes for interesting copy for those of us who write about the church. Truces are unsatisfying and instability is exciting and theological civil wars can be worth waging. But there is no sign as yet that Francis’s liberalization is bringing his lapsed-Catholic admirers back to the pews; from Germany to Australia to his native Latin America, the church’s institutional decline continues. And sustaining a for-the-time-being Catholicism, as his immediate predecessors did, is not an achievement to be lightly dismissed. Whereas accelerating division when your office is charged with maintaining unity and continuity is a serious business — especially when the eventual resolution is so bafflingly difficult to envision or predict. It is wise for Francis’ Catholic critics to temper our presumption, always, by acknowledging the possibility that we are misled or missing something, and that this story could end with this popular pope proven to be visionary and heroic. But to choose a path that might have only two destinations — hero or heretic — is also an act of presumption, even for a pope. Especially for a pope.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.