|

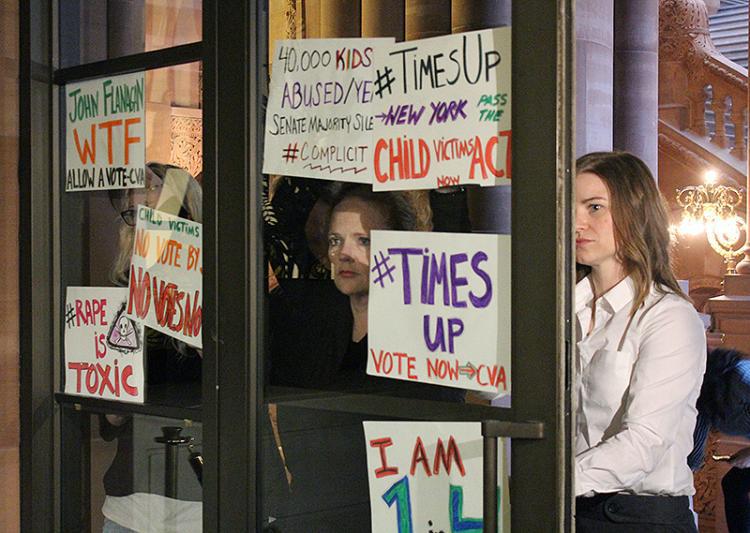

Child Victims Act left behind in state’s budget, kept alive by survivors

By Elizabeth Floyd Mair

ALBANY COUNTY — The state budget left out the Child Victims Act — a bill supported by the governor and the State Assembly — that would have extended the statute of limitations for child victims of sexual assault, but adult survivors are not giving up. The bill never made it to the State Senate floor, so the GOP majority leader is the focus of upcoming efforts. Meanwhile, a group called Lawyers Helping Survivors of Child Sex Abuse released a document entitled “Hidden Disgrace III” on March 29, listing all of the priests who have worked for the Albany Diocese and have been accused of sexual abuse, what they are alleged to have done, and all the places they have worked. Attorney Jerry Kristal of Lawyers Helping Survivors of Child Sex Abuse told The Enterprise that the statute of limitations in these cases should be extended by passing the Child Victims Act, and that the Albany Diocese should create an independent reconciliation compensation program that would allow people alleging sexual abuse to get some “recognition that this really happened and some measure of the church taking responsibility.” Reaching a settlement through a compensation program means that an individual victim would never be able to bring a claim in the future. “What you give up if you settle, is the right to ever sue, if you get that right,” said Kristal, who is a managing attorney with the firm Weitz & Luxenberg in the New York metropolitan area. Currently, under New York law, child victims must bring charges by their 23rd birthday; most states allow more time. The Child Victims Act would extend this to age 28 for criminal claims, and age 50 for civil. The act also provided a look-back year that would allow claims from any time period to be brought. “Most survivors are not even able to process what happened to them, until decades later,” Kristal said. Why so long? “Let’s assume that you’re a 9-year-old boy being anally raped by a priest. It’s not only by an adult, but a trusted adult, and an adult supposedly speaking for God,” Kristal said. Children think no one will believe them, Kristal said. In some cases, they might believe that their parents will believe them and that they will kill the priest. In any case, this secret, he said, is a “psychological trauma of the deepest possible proportions.” The bill should also include a “look-back,” Kristal said, “so that people currently time-barred would have, say, a one-year window for filing claims.” The Catholic Church and the Boy Scouts of America opposed the bill. Views of local state repsGeorge Amedore Jr., a Republican in the GOP-dominated State Senate, told The Enterprise last week, “I support justice.” He represents the 46th District, which stretches 140 miles and covers parts of five counties — Albany, Greene, Montgomery, Schenectady, and Ulster. Amedore said he would need to see the language of any bill before saying definitively whether he would vote for it. But Amedore called the acts of predators who abuse children “very evil” and said, “The book should be thrown at those predators that are doing that.” Amedore said it was “unfortunate that the governor, the speaker of the assembly, as well as the majority leader and the Independent Democratic Conference leader all agreed to take it out of the budget.” Amedore added, “Hopefully, it will be addressed by June,” referring to the end of the session. Assemblywoman Patricia Fahy, a Democrat in a Democrat-dominated house, said, “I’m not out to bankrupt anybody, and this is not about trying to do harm to good institutions. For me, this is about giving people their day in court, many of whom have waited many years. It’s overdue justice.” She represents the 109th District covering the towns of Bethlehem, Guilderland, and New Scotland, and parts of the city of Albany. Some of the opposition, Fahy said, falls along religious lines, and “not just Republicans versus Democrats.” There are 42 priests’ names on the “Hidden Disgrace III” list, including two with connections to Guilderland: — Edward N. Leroux worked at St. Madeleine Sophie in Guilderland in 1970 and, the report alleges, “abused three boys in the late 1970s and early 1908s”; and — James J. Rosch who worked at St. Madeleine Sophie from 1985 through 1995 and is alleged, the report says, to have abused a teenage boy in the 1980s. Leroux is dead and Rosch said he had no comment. Both of them are on an Albany Diocese list of clergy found to have abused minors. Both Leroux and Rosch were removed from the priesthood in 2002. Survivor’s viewRichard Tollner of Rensselaerville came forward about his abuse almost right away, as a teenager, as soon as he figured out that what the priest was doing was wrong and constituted abuse, he said. Tollner says he was abused when he was 15 and 16 by Alan Placa, a priest at the school he attended, St. Pius X Preparatory Seminary in Uniondale, New York. He was sexually molested when he was 17 and still a student, Tollner said. Placa could not be reached for comment. Asked if he felt awkward having to see Placa around school after he had reported the molestation, Tollner said no. “Once I understood what was going on, it was more of, ‘This guy is harmful,’” Tollner said. Tollner recounted the way his abuse ended, at a funeral home during his father’s wake: His mother had said to Placa during the wake, “Richard looks upset. Why don’t you go talk to him?” Tollner overheard his mother saying that and realized “in that fraction of a second” that his father was no longer around to take care of him, and that he needed to take care of himself. He left the funeral home, turned around, and waited just outside the door. When Placa walked through it, he grabbed the priest and said to him, “Don’t ever fucking touch me again or I’ll kill you,” Tollner recounted. Tollner had warned his friends about Placa before that, he told The Enterprise. It was soon after that that he reported the abuse. He reported it three times, he says — to a math teacher, to the head of the seminary, and to another priest — and nothing was done. It was in 2002, he says — after “Boston started to blow up,” referring to the explosive exposé of priests’ sexual abuse of children that stemmed from a Boston Globe investigation — that Tollner went public with his story in the press. In 2006, when he was 47, Tollner requested a canonical penal trial, he says. The trial, which was assigned to the Albany Diocese by the Rockville Centre Diocese on Long Island, took more than three years, he said. During the trial, the church made it practically impossible for some victims who were to serve as witnesses in his case to testify, Tollner said, by making appointments and then changing the time, or by changing the place of an appointment — sometimes to a town 50 to 100 miles away — several times, “making it hard, for the person who is having a hard time, to testify,” Tollner said. He explained that many survivors find it very difficult to talk about their experiences. No one from the Roman Catholic Church ever called or wrote informing him of the decision from the trial, Tollner said; he found out from a Newsday reporter that the church had decided his allegations were unsubstantiated. “That’s the terminology they use,” he said this week of the word “unsubstantiated.” After Tollner reported his abuse, Placa went on to become an attorney and to represent the church in numerous claims of sex abuse by priests, Tollner said. Tollner added that Placa is a good friend of former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani. A Suffolk County Supreme Court Special Grand Jury investigated the Diocese of Rockville Centre, its priests, and its parishes, because of reports of many instances of sexual abuse by priests working in the diocese. Included in its report are Placa, who is referred to as Priest F, and Tollner. In its report, the grand jury concluded: “[O]fficials in the Diocese failed in their responsibility to protect children. They ignored credible complaints about the sexually abusive behaviors of priests. They failed to act on obvious warning signs of sexual abuse including instances where they were aware that priests had children in their private rooms in the rectory overnight, that priests were drinking alcohol with underage children and exposing them to pornography. Even where a priest disclosed sexually abusive behavior with children officials failed to act to remove him from ministry.” The report also states that diocesan officials “agreed to engage in conduct that resulted in the prevention, hindrance and delay in the discovery of criminal conduct by priests.” It says, “They conceived and agreed to a plan using deception and intimidation to prevent victims from seeking legal solutions to their problems.” The report says, too, that the conduct of certain diocesan officials would have warranted criminal prosecution, but that the existing statutes are inadequate. The report concludes that the statute of limitations should be extended, not just to age 28, but to age 33. It also says that mandatory reporting directly to law-enforcement officials should be expanded to include cases that involve abuse by people other than parents and guardians, to include people working in any capacity — ministry, employment, or volunteer — in a religious institution. Tollner has kept his faith, although he attends an Episcopal church now and has for over 20 years. He was married there in 1989 and is head of his church’s board of directors and runs the church’s events. “I consider myself an Episcopalian because the Catholic Church left me. I didn’t leave the Catholic Church,” Tollner said, referring to the way that church officials ignored his situation. If the Child Victim Act is passed, with a “look-back” clause allowing one additional year for people who are time-barred to bring cases, Tollner said, he plans to bring civil charges against Placa. Church’s viewThe Diocese of Albany is committed to providing meaningful support to survivors of clergy sexual abuse, said Mary DeTurris Poust, diocesan spokeswoman, this week in an email, responding to Enterprise questions. The diocese believes that both the criminal and civil statute of limitations should be extended, DeTurris Poust said. “We support complete elimination of the criminal statute of limitations and a substantial increase in the civil,” said DeTurris Poust. “Through the NYS Catholic Conference, we oppose an unlimited retroactive window that would allow for claims going back 60 and 70 years to be revived.” In 2004, the Albany Diocese established an independent reconciliation program for victims and survivors of clergy sexual abuse and became one of the first dioceses in the nation to do so, DeTurris Poust said. The Independent Mediation Assistance Program, or IMAP, was developed and overseen by retired New York State Court of Appeals Judge Howard Levine and funded by the diocese, she said. Judge Levine reviewed allegations and determined settlements in his sole discretion for more than 40 individuals and provided assistance totaling nearly $3 million, DeTurris Poust said. The program was originally intended to operate for a year but was extended several times, concluding two years later after all the requests for assistance were addressed, she said. Today, the diocese continues to provide financial support, counseling, and other assistance, based on the procedures and protocols of the IMAP program, to people who were sexually abused by a priest or employee of the diocese, said DeTurris Poust. Although the official IMAP program has ended, DeTurris Poust said, the diocese “has continued to assist those who come forward.” She added, “We encourage anyone who knows of or suspects sexual abuse of a minor to contact a law enforcement agency. Anyone wishing to report a complaint of clergy sexual misconduct in the Albany Diocese can contact our Diocesan Assistance Coordinator at 518-453-6646.” Kristal, the attorney from Lawyers Helping Survivors of Child Sex Abuse, responded, “It can take years or even decades for survivors of clergy sex abuse to come to terms with their abuse and gather the courage to speak out. It’s been more than 10 years since the Albany Diocese closed its mediation program and there are plenty who were unaware or unable to participate in the previous program who are currently suffering and need support. “It is unacceptable to suggest that a program launched more than a decade ago is sufficient to address this ongoing, persistent problem. We know there are those who are hurting in Albany who currently do not have the same options as survivors in other parts of the state, and the diocese should support these survivors now with the chance to seek healing and relief.” DeTurris Poust, in turn, responded through The Enterprise, “This is simply not the case. Today, the Albany Diocese continues to provide financial support, counseling and other assistance, based on the procedures and protocols of the IMAP program, to individuals who were sexually abused by a priest or employee of the Diocese.” Anyone wishing to report a complaint of clergy sexual misconduct in the Albany Diocese is encouraged to contact the Diocesan Assistance Coordinator to start the process and get the support they need, DeTurris Poust said. If a survivor has a claim that has not previously been reported, he or she should report the incident to law enforcement as well, she added. DeTurris Poust went on to say that no priest or deacon who is determined to have sexually abused a minor at any time is permitted to remain in ministry, nor can he be transferred into, out of, or within the diocese, DeTurris Poust said; any employee who is determined to have sexually abused a minor also will be removed from diocesan employment. There are no priests or deacons in ministry nor any employees serving the diocese today whom the diocese has determined sexually abused a minor at any time, she said; all allegations of clergy sexual abuse, regardless of when the incident was alleged to have occurred, are reported to law-enforcement agencies. DeTurris Poust said the diocese cooperates fully in all investigations. The diocese conducts mandatory background checks — repeated periodically — on priests, deacons, employees and volunteers who interact with children, said the spokeswoman. The diocese provides age-appropriate safety training programs for children, to help them recognize the warning signs of inappropriate behavior and to protect themselves by reporting the behavior, according to DeTurris Poust; training is also provided to parents, teachers, and volunteers on an ongoing basis to help them recognize potential signs of abuse. Asked about Tollner’s claim that the diocese never told him about the conclusion of his case, DeTurris Poust said that that would have been up to the Rockville Centre Diocese to do, since Placa was a priest there and never served in Albany. Tollner said that Albany had referred to him Rockville Centre, and Rockville Centre referred him to Albany.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.