|

Priest accused in 124 Guam sex abuse cases ages quietly, alone

By Haidee V. Eugenio And Dana Williams

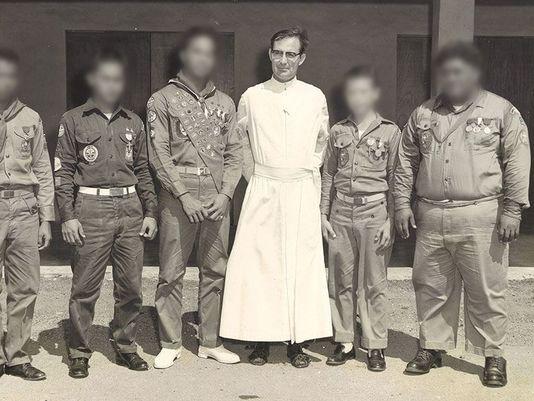

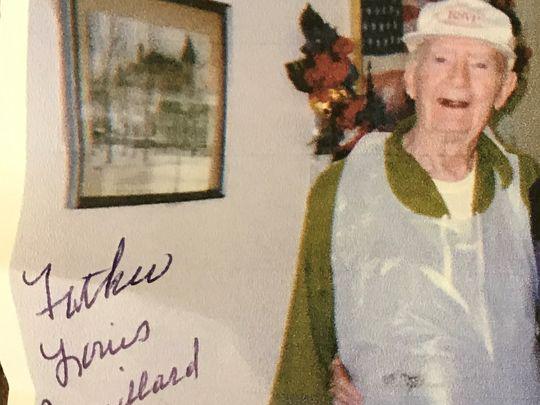

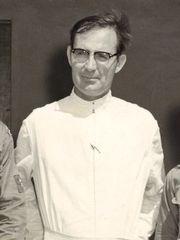

[with video] PINE CITY, Minn. – Statues of the Virgin Mary and portraits of Jesus loom over Louis Brouillard in his small apartment. He lives alone, two blocks from Pine City Elementary School and across the street from St. Mary’s Catholic preschool — close enough to hear children’s laughter when they play at recess. The retired priest no longer wears a collar, but the people in this small town an hour north of Minnesota’s Twin Cities still call him "Father." He is 96 years old. Brouillard's peaceful life stands in stark contrast to the torment of 122 men and two women – all middle-age or retired now — who accuse him of sexually molesting them as children on the island of Guam. They have broken long-held silences and filed lawsuits. Some have protested and begged for justice. Somehave left the church. A long time ago, some of them complained. Brouillard confessed, and was told to pray and try harder. Eventually, the island's Catholic church simply sent Brouillard away. The priest is frail now. He has wispy gray hair. A single tooth protrudes from his upper gums. But once, he was young and robust, a leader of the Boy Scouts and a respected figure on Guam. As of May 4, there were 166 child sex abuse lawsuits on Guam filed against the Archdiocese of Agana, the Boy Scouts of America, 19 clergy members including Brouillard and others affiliated with the church on the island. Brouillard's attorney, Thomas Wieser, declined to talk about the cases. Only one of the accused has filed a response to the lawsuits. Attorneys for the church, Brouillard and others have been laying the groundwork for mediation, scheduled for September, and eventual settlements. Brouillard was deposed over several days in November, and sworn statements are being taken from plaintiffs in the cases. Brouillard is the only person accused in the lawsuits who has publicly admitted to abusing children while on Guam. An ordinary upbringingLouis Brouillard grew up not too far away from where he lives now, in the working-class Minneapolis suburb of Columbia Heights, Minn. He recalls a comfortable home where he lived with his mother, Opal, his father, Raymond, and four younger siblings. Brouillard's father had a steady job with a steady salary as a motorman for the the streetcar company. Although the family is Catholic, Brouillard said he wasn’t particularly religious as a child. Yet he would stop at the neighborhood church to pray on his way home from school. The priest suggested Brouillard consider a vocation. “I thought that was a good idea,” Brouillard said in an interview with USA TODAY NETWORK in September. He would speak only of his past and his passion for the church, not of the accusations that followed him home from Guam. A man of faithThe St. Paul Seminary on the banks of the Mississippi River opened its doors in 1894. It was founded by the highly influential Archbishop John Ireland, known for bringing Irish Catholic families from urban slums to settle the farmland of rural Minnesota. He envisioned a church that was "robust, eminently visible and characteristically American," according to the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. It is here that Louis Brouillard came in the 1940s. An article in a mission magazine published by Franciscan Capuchin friars in 1947, his last year in seminary, led him to the improbable island of Guam. The majority Catholic island, in shambles afterWorld War II, needed priests. The tropical climate sounded more appealing than frigid Minnesota winters. “I thought it was a very good place to start my career,” Brouillard said. Fewer than 60,000 people lived on Guam when Brouillard arrived. He was ordained as a Catholic priest on Guam in December 1948 and would serve on the island for nearly 33 years as a teacher, pastor and scoutmaster. An unremarkable teacherThe high school boys called him "Louis Leklok." Leklok means masturbation in Chamoru, the language spoken on the island. Behind his back, students laughed about the tall, slender teacher with hairy arms. “I don’t know if he knew about that nickname. It was meant as a joke at the time,” said Chris Duenas, now retired, who was a student at Father Dueñas Memorial School from the late 1960s to 1973. As a high school teacher, Brouillard had a reputation for giving easy tests and lacking the ability to control his class. Kids listened to transistor radios, talked among themselves, even threw erasers at his back. If students misbehaved, he occasionally rapped them with his knuckles or swatted at them with a rolled-up newspaper, Duenas recalled. Brouillard “really did not pay much attention to that, and the class was kind of loose, so to speak,” said David Sablan, a former student. Sablan is now a businessman and president of Concerned Catholics of Guam, the organization that helped bring sexual abuse charges against Guam's former archbishop Anthony Apuron to light. Earlier this year, a Vatican tribunal found Apuron “guilty of certain accusations” related to the sexual abuse of minors. Brouillard “was not necessarily someone that would stand out. He would not be one of those priests that we would have any kind of affinity toward,” Sablan said. He didn't learn of the accusations against Brouillard until 2016. That lackadaisical attitude in class also governed his appearance, former parishioner Francisco T. San Nicolas said. He recalls Brouillard's days at San Isidro Church in the rural community of Malojloj in the mid-1970s. Brouillard wore shirts with holes or stains and mismatched sandals, even those he would find at the beach, so long as his feet were protected, San Nicolas said. He dressed up only for Mass. And he always wanted to be outside and liked swimming, San Nicolas said. Robert Patrick S. Palomo, now 63, was a seminarian who decided not to become a priest after studying with Brouillard. “I started seeing things that I knew were wrong,” said Palomo, who is not among those who filed lawsuits. He said Brouillard would ask detailed questions about masturbation during confession. “He didn’t physically abuse me, but mentally, he was abusive.” He said he and other students suspected Brouillard was engaged in inappropriate activity. While he never shared his suspicion with his parents, he warned younger boys not to go on swimming trips with the priest, and he told his cousins not to join the Boy Scouts. Swimming lessons The island, with its steamy jungles, still felt wild in those days. The jungles were so dense that the last Japanese soldier who fled to the island's interior during World War II didn't emerge until 1972. To escape the nearly constant humidity, island kids craved outings to the swimming holes filled with cool fresh water rolling over limestone and volcanic rock. Brouillard would teach the boys to swim. One of those boys is identified in one of the 124 lawsuits as R.A.S. In 1955, Brouillard was a parish priest at the Santa Teresita Church in Mangilao. R.A.S, the lawsuit recounts, was 10 or 11 then, and an altar boy who thought he might one day become a priest. Brouillard asked the boy's parents if the child could help around the church. In those days, few island Catholics would think to question the church or the intentions of its priest. The boy's parents "gave consent without the slightest of doubt,” the lawsuit states. In the lawsuit, R.A.S. accuses Brouillard of fondling him. The priest also made the boy masturbate him, the lawsuit says. When he was done, he gave the boy “a jock-strap and a bunch of coins, and instructed R.A.S. not to tell his parents.” Another time, the priest took R.A.S. and some other boys to swim, the lawsuit recounts. Brouillard told the boys to remove their clothes. R.A.S. refused and went into the water fully clothed. Brouillard, R.A.S. claims in the lawsuit, groped him during the swimming lesson, and when he tried to get away Brouillard held his head underwater. After that incident, according to the lawsuit, “R.A.S. lost his faith in the church, quit being an altar boy and was no longer interested in the priesthood. To this day, R.A.S. refused to go to church.” Others tell eerily similar stories in the lawsuits. The stories span several decades and they often recall a favorite spot at the Lonfit River, a remote waterway that cuts through Guam’s central jungle as it flows from the hills. Some boys recall Boy Scout camp-outs that took an ugly turn, the lawsuits said. At that time on Guam, the church required altar boys to join the Boy Scouts. In an affidavit filed with the court in Guam, Brouillard described “managing the Boy Scouts, where I served as president for the Scouts on Guam.” Felix Manglona's lawsuit describes his time as an altar boy and Boy Scout in 1971 when he was 13. He recalled Brouillard walking naked around the church rectory and showing the boys pornography. Manglona accuses Brouillard of assaulting him at a Boy Scout campout as the priest went from tent to tent conducting a head count. Brouillard, the lawsuit says, performed oral sex on the boy and his tentmate. Years later, when Manglona was a police cadet, he recalled seeing a complaint involving Brouillard and a minor boy at another church. Now, decades later, any complaints are lost to time. The statute of limitations has expired and police on Guam said last year they could locate no records involving Brouillard nor could they confirm that any parents or children ever filed a complaint. Scout Executive/CEO Jeff Sulzbach of the Boy Scouts of America Aloha Council wrote in an email that the organization barred Brouillard from participation in the scouting program when it learned of the allegations. The Boy Scouts will not confirm Brouillard’s time as a scout leader. “The allegations about Father Brouillard runs counter to everything for which the BSA stands," Sulzbach wrote in an email. Not all of the accusers were altar boys or Scouts. In 1971, a boy identified as B.J. in his lawsuit, was hanging out with friends in front of a store when Brouillard pulled up in his Volkswagen. He told the boys he was a priest and a scoutmaster, and offered to teach the boys to swim at the Lonfit River. At the swimming hole, Brouillard removed his clothes and told the boys to do the same, B.J., who was 11 or 12 at the time, recalls feeling uncomfortable, but pushed those feelings aside because he "was just happy that Brouillard invited (him) to go swimming, because opportunities like this didn't happen very often for (him),” the lawsuit said. Afterward, Brouillard took the boys out to eat. B.J. recalls another trip to the river — this time just he and Brouillard under the pretense that the priest would teach him survival skills, the lawsuit recounts. Brouillard allegedly tied the boy up and performed oral sex on him. Then, the priest gave him water. “B.J. believes that there was something in the water, because after drinking it B.J. began to feel weird,” the lawsuit states. Brouillard then forced B.J. to perform oral sex on him, the lawsuit states, then raped him repeatedly. When Brouillard finally untied the boy, he explained that the act was similar to confession — just between them and God. Prayers as penanceIndeed, Brouillard eventually confessed his transgressions in a 2016 affidavit obtained by an investigator and filed with many of the lawsuits. Brouillard faces no criminal charges for his acts, nor can he be charged under Guam law. The statute of limitations has long expired. The Archdiocese of Agana is paying for Brouillard’s legal representation. “I did touch the penises of some of the boys and some of the boys did perform oral sex on me,” Brouillard wrote in theaffidavit. “There may have been 20 or more boys involved.” He said encounters may have also taken place at the Catholic schools where he taught. “At the time, I did believe that the boys enjoyed the sexual contact and I also had self-gratification as well.” That affidavit, however, contained a startling revelation. Brouillard said in the affidavit that he had been found out decades before and had confessed to a superior. “While in Guam my actions were discussed and confessed to area priests as well as Bishop Apollinaris Baumgartner, who had approached me to talk about the situation. I was told to try to do better and say prayers as a penance,” Brouillard said. Some of the men also say that as boys, they or their parents reported the abuse. Church officials, they say, turned them away. In 1981, Brouillard was sent to Minnesota for "help with his personal problems," said Kyle Eller, communications director for the Diocese of Duluth, in a statement last year. Brouillard served in three churches in remote parts of Minnesota — Beroun, Keewatin and Kelly Lake, according to the diocese. "In 1985, Father Bouillard’s faculties to serve as a priest in the Duluth Diocese were revoked after questions were raised about a guest from Guam staying with him," Eller said. Three of the lawsuits filed on Guam last year accuse Brouillard of paying to bring boys from Guam to Minnesota, where he continued to abuse them. One of the lawsuits alleges he moved a boy into a two-bedroom retirement home apartment in Pine City where he lived with his elderly parents. Brouillard would have been about 60 at the time. Now in Pine City, Brouillard has a simple altar under his front window. That’s where he performs Mass for himself. Sometimes he gets tired of standing and takes breaks during his own Masses. Brouillard still receives a $550 stipend from the Guam archdiocese each month. For more than 20 years Brouillard volunteered daily for a Meals on Wheels shift at the Pine City Senior Center, waking at 5:30 a.m. Monday through Friday to prepare food and serve it to other seniors. He thinks of it as atonement. “They needed help, so I helped,” Brouillard said. “If you do a good deed, you don’t have to broadcast it.” His life is simple. He watches religious programs and cartoons on TV. He reads on his porch. Twice a week, he ventures out to attend church and shop. When a reporter stopped by Brouillard's home in October, Brouillard's lawyer turned her away. Wieser described his client as “vulnerable.” But Brouillard wanted to chat when the reporter returned in March. He called for her to enter when she knocked on the door. The priest, wearing long johns with a blanket draped over his lap, told her to wait a moment for him to insert "his ears," as he called his hearing aids, so they could talk. As the talk turned to his alleged actions on Guam, Brouillard was full of regret. He admitted touching the boys, but said he didn't know at the time it would be harmful to both the boys and the church. “I’m sorry for all that happened. I regarded them as my friends. In fact, I still do,” Brouillard said. “As youths, they were appreciative of what I could do for them. “There’s so much I could have done better," he said. "I’m afraid I was thinking more of what I wanted to do, rather than what God called me to do.” He is unconcerned about a potential trial — “I let the lawyer worry about that,” he says — and leaves his fate to God. “I’ve learned in my long life that I leave everything in the hands of God, because he’s after all, my destiny,” Brouillard said. “Whatever he wills is my will.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.