|

He Was Convicted of Molesting a 6-Year Old. Should He Have a Future in Baseball?

By Kurt Streeter

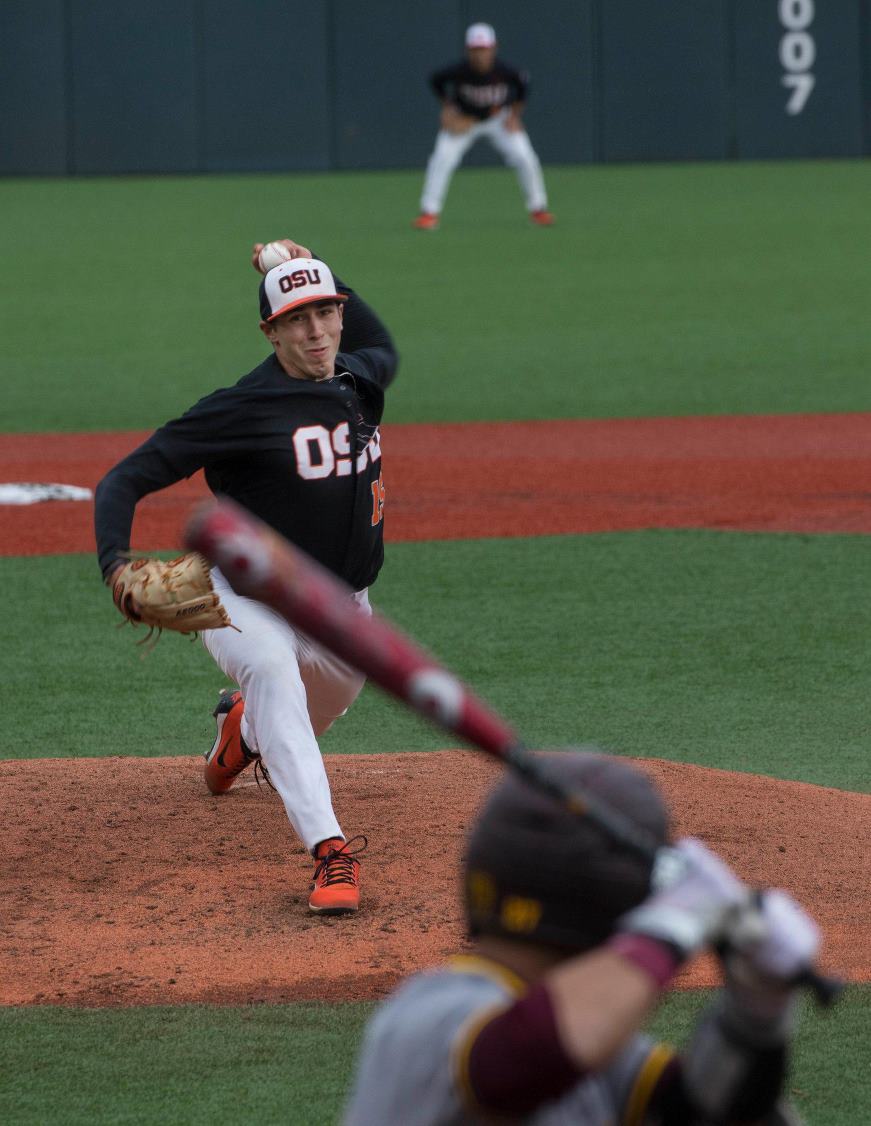

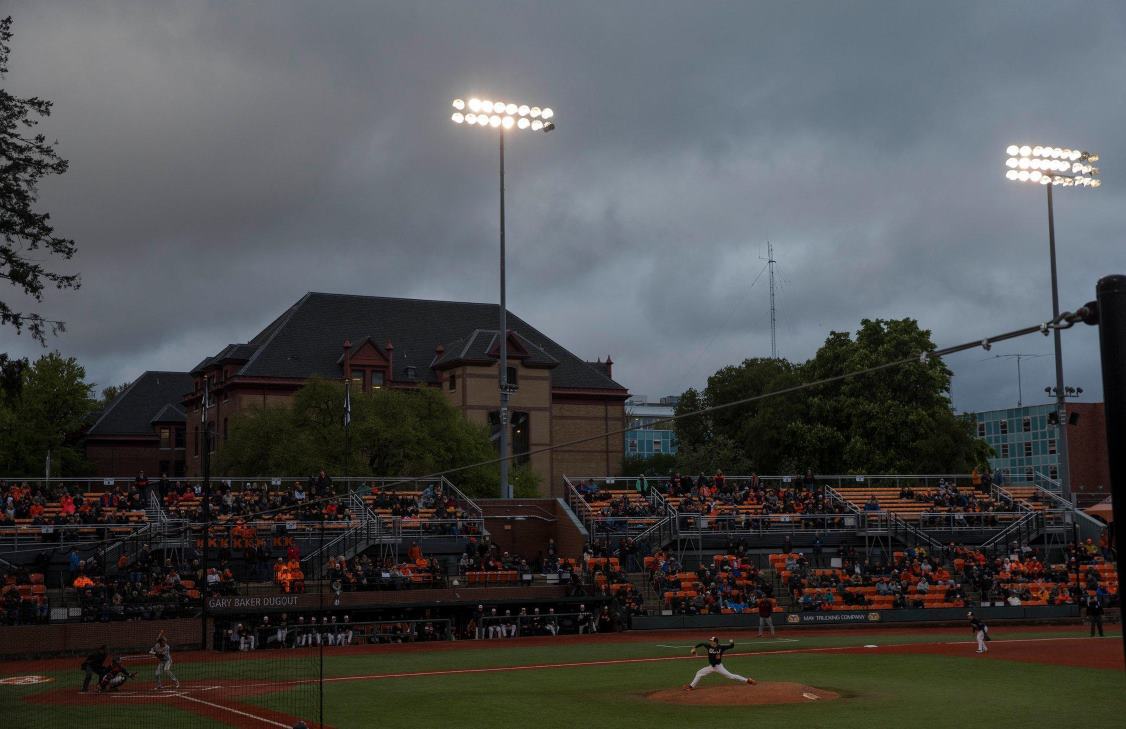

CORVALLIS, Ore. — Luke Heimlich, one of the best players in college baseball, and certainly its most controversial, strode to the mound, dusted away a patch of dirt with his cleats and lined up for his first pitch. The home crowd of nearly 3,000, most in orange and black, the colors of Oregon State, cheered, “Luke! Luke! Luke!” They wanted a victory against Arizona State, one of their biggest rivals. More than that, they wanted a performance that would hark back to a different time — the time before anyone had heard that Heimlich, 22, their hero, had pleaded guilty to a felony: sexually molesting his 6-year-old niece when he was 15. Otherwise, this game in Goss Stadium seemed completely normal, as has been true all season, which has unfolded in a surprisingly ordinary way. The Beavers are again among the elite. They have a good chance of making it back to the College World Series in June. They might win the national championship. But, given his past, the question remained, why was Heimlich even on the mound? In a series of interviews with The New York Times this weekend, Heimlich flatly denied committing the crime he had admitted to, saying he pleaded guilty to quickly dispense with the case and for the sake of family relations. “Nothing ever happened,” he said, when asked for specifics about what might have occurred between him and his niece. The girl’s mother, whose name is being withheld to protect the identity of the victim, said her daughter’s account is the truth. “There is no way he didn’t do it,” she said in an interview with The Times in which she described her daughter’s descriptions of abuse as “very specific.” Heimlich’s assertion of his innocence is not likely to stop the questions that surround Oregon State and its baseball team. Questions that both Heimlich’s critics and his fans have been asking for months. Should the fact he has fulfilled his court obligations be enough, or was the nature of the crime so egregious he should never be let back on the team? What, now, to make of his denial and the insistence of the victim’s mother that it did occur? And how does the victim’s enduring anguish figure into a quest for redemption and a new beginning? The Past Goes PublicLast June, when The Oregonian first reported Heimlich’s guilty plea, it said he originally had faced two charges stemming from incidents between 2009 and 2011. The victim is the daughter of one of Heimlich’s older brothers. She has not been identified by name. According to court records, the newspaper said, she told investigators that she was in Heimlich’s bedroom at his home south of Seattle when he pulled her underwear down and “touched her on both the inside and outside.” The Oregonian quoted the documents as saying, “She told him to stop, but he wouldn’t.” As part of a plea deal, reached when Heimlich was 16, one of the charges was dropped and he was placed on two years’ probation, took court-ordered classes and had to register for five years as a Level 1 sex offender, a designation the state of Washington uses for someone considered of low risk to the community and unlikely to become a repeat offender. Heimlich also had to write a letter apologizing to his niece. Heimlich’s case might never have been made public if not for the fact that, years later, while pitching for Oregon State, he failed to update his whereabouts for a state registry of sex offenders, which led to a police citation, which in turn tipped reporters to his case. Heimlich’s court records were sealed last August, two months after the first news stories broke. That month, five years after the date of his plea, he said, the records were expunged. He no longer has to register as a sex offender. The news of the case roiled the Oregon State campus and made national headlines. Heimlich left the baseball team, saying he did not want to be a distraction. Other than a brief statement in which he said he had taken responsibility for his conduct as a teenager, he declined to comment. Now, on Saturday, in the interviews with The Times, he spoke about what he called his “unique situation.” Asked about the critics who have demanded that Oregon State refuse to let him rejoin the team, he was succinct: “I don’t have anything to tell them,” he said. “They can have their opinions of me. Ultimately the people around me know who I am. That is what matters. Everybody else can say what they want.” The case, he said, is “a delicate family situation,” though he declined to go into the details. Did he abuse his niece? Heimlich insisted he did not. “I always denied anything ever happened,” he said. “Even after I pled guilty, which was a decision me and my parents thought was the best option to move forward as a family. And after that, even when I was going through counseling and treatment, I maintained my innocence the whole time.” There was no interaction with his niece that he could imagine would have been misinterpreted, he said, adding, “Nothing ever happened, so there is no incident to look back on.” Heimlich had written an apology to the victim, but he now says he did so because “there were certain requirements when going through counseling that had to be done to finish.” He suggested the idea that his niece would face aggressive questioning in a trial factored into his decision to plead guilty. “Trials aren’t fun things and, as I said before, it is a delicate situation within a family,” he said. “We didn’t want to do anything to complicate things.” Pleading out held the promise that, “five years from the date, everything would go back to normal.” Heimlich said he was ready to play in the major leagues. After spending much of this season trying hard to “prove people wrong” with his pitching, he said that he is feeling comfortable again, both on the mound and off. He said that he has talked to several big-league general managers, even to owners, and that he has been contacted by most teams. Officials with major-league baseball teams declined to speak on the record about Heimlich. The girl’s mother, divorced from Heimlich’s brother since around the time the allegations surfaced, is adamant in her belief that the pitcher’s dream never be fulfilled. “My opinion is that he should not be able to play,” she said, not in college nor the pros. For her daughter, she said, the case “will only go away when Luke is out of the light. If he makes it to the big leagues, he will be in the light forever. Any accomplishment he makes will shine the light on her. It could be 50 years from now, he gets inducted into the Hall of Fame, they will bring up this story. “I don’t think he is a terrible person,” she added. “I think he did a terrible thing.” A Coach Backs His PlayerAlthough Heimlich has begun to talk about his troubles, the silence around him among Oregon State officials has not cracked. Last year, after Heimlich’s guilty plea had been made public, the Oregon State coach, Pat Casey, a two-time national title winner, denied knowing about Heimlich’s past while he was recruiting him to come to Corvallis. This season, Casey has said little more than that he supports his star. “He’s a fine young man,” Casey told reporters last summer, “and for every second that he has been on this campus, on and off the field, he has been a first-class individual — someone his family should be proud of, our community should be proud of and his team is proud of.” Citing confidentiality laws, university officials have refused to say what they knew about Heimlich’s background. Coach Casey and Steve Clark, a university spokesman, would not grant interviews with The Times, nor would the Oregon State president, Ed Ray. (Ray was chairman of the N.C.A.A.’s executive committee in 2012 when it leveled unusually stiff penalties against Penn State over the sexual abuse of children by Jerry Sandusky, a former Nittany Lions football coach.) Ray had issued a statement after the university reviewed the case, saying in part it would “welcome all educationally qualified students, including those rehabilitated from past crimes.” In his interviews with The Times, Heimlich said that he had not talked about his case with Casey before his plea went public. “It is my job to report to the local law enforcement,” he said. “If that didn’t get conveyed to the university then I would not know, I was not a part of that.” When the initial report about him was published, the immediate question was whether Heimlich would stay on the team, which was advancing in the N.C.A.A. tournament. Ray, the Oregon State president, supported Heimlich’s voluntary withdrawal from the team last season. He also left the door open for a return. “If Luke wishes to do so,” he said in a written statement at the time, “I support him continuing his education at Oregon State and rejoining the baseball team.” Heimlich would have turned professional if he could have. More than 1,200 players were chosen in last summer’s major league draft, but Heimlich, who was eligible for selection, was not one of them — though he had once been projected to be a high pick. So, with the goal still to make the majors, he returned to the Oregon State team this year. He has dominated the mound, but not quite as overwhelmingly as before. Last year his pitches were nearly unhittable: his 0.76 earned run average was among the lowest in college baseball. This year, though he is 11-1, that number hovers around 3.00.

Cheers in Corvallis

In Corvallis, where baseball players are treated with the reverence many universities save for football players, Heimlich remains deeply respected among fans. At Goss Stadium, as Heimlich pitched in the game against Arizona State, support was obvious. Most fans stood adamantly behind him. Some said they had quit paying attention to the Heimlich story after February, when the university announced a policy some called the Heimlich Rule. It requires recently accepted and continuing students to reveal any felony convictions, or sex offender status. Those with criminal backgrounds will have their admissions reviewed. Others said they had given lengthy consideration to the case and had decided juvenile crimes should be forgiven — even the most heinous — once justice, and in some instances prison time, has been served. Still others said the news media should not have written about Heimlich’s past. “He was doing everything he was supposed to do, everything the courts asked,” said Raymond Brooks, a retired Oregon State professor. “Why even dig it up?” In the ninth inning of the game against Arizona State, Heimlich was taken off the mound after a sudden string of off-the-mark pitches. He walked toward his teammates with a grimace. The crowd gave him another ovation. That kind of support doesn’t sit well with everyone. “Even after all the heightened attention about abuse since last year, it’s a bubble in Corvallis when it comes to this case,” said Brenda Tracy, 44, one of Oregon’s most prominent victims’ rights activists. A registered nurse, Tracy received national attention in 2014 when she said that she had been raped in the late 1990s by a group that included two members of the Oregon State football team. After going public with her story, she spent time as a consultant for the school on assault prevention and policy. Ray, the Oregon State president, hailed Tracy for her efforts to highlight the problem of on-campus sexual abuse. But he and Tracy don’t agree about Heimlich. Playing sports at any level is a privilege, not a right, Tracy said, and Heimlich should not be on the team. Let him stay in school, she said; let him graduate and move on. But just like the mother of Heimlich’s niece, she said she does not think anyone who has pleaded guilty to molestation should be wearing a university sports uniform, or that he should be cheered. “What kind of message does that send our kids?” she asked. “We have now normalized this behavior. The feeling at Oregon State right now is that our team is winning, so they’ve moved on. What does that say to the little girl in this case? What does it say to all survivors?” Madeline Gorchels, 24, said that she is a sexual abuse survivor. She said she was molested as a child. She is also an Oregon State baseball season-ticket holder. Last June, when she heard the news about Heimlich, she said she walked into a closet, crumpled to the floor and shook for hours. But she has found ways to be loyal to Oregon State. When she heard Heimlich had left the team, she traveled to Omaha for the College World Series last year. When he returned to the team this year, she said she felt nauseated. But she shows up for every game she can. She applauds for the offense, but she sits stone quiet when Heimlich pitches. “I feel like it is important to be there to represent my point of view,” she said. “Even if I am not actively saying something, it is good for me to be there to say that I don’t think what has happened is right. Part of it is I don’t want what he did affecting my behavior. But part of it is being there as a witness to the fact that this is wrong.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.