Sex and the Liberal Politician: a New York Story

By Ginia Bellafante

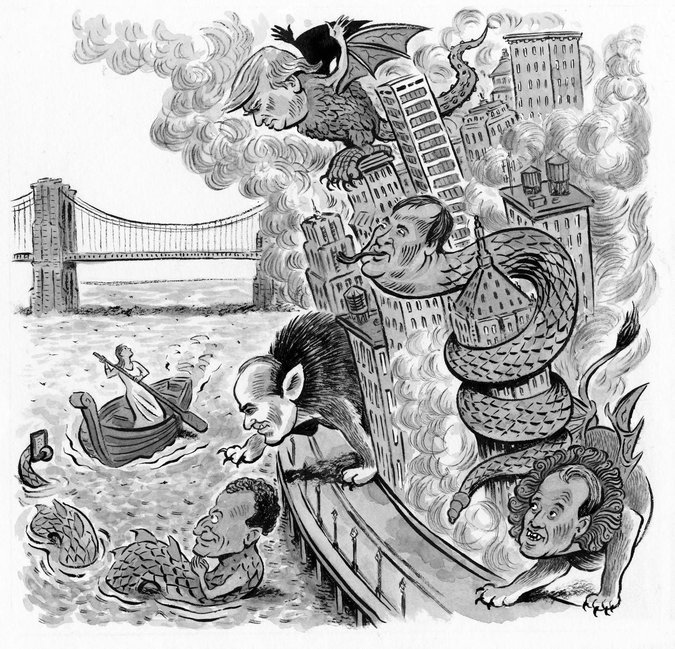

In New York, the week of May 7 began with the sudden resignation of the state’s attorney general, Eric T. Schneiderman, over allegations that he had physically abused four women he had been seeing, and ended with the conviction of Sheldon Silver, the state’s once powerful Democratic Assembly speaker, on federal corruption charges. Although not necessarily an ordinary week, it was certainly a symbolic one. Abuses of power, sexual and ethical, have supplied the arc of the state’s political narrative for so long that it is hard to know how New York has managed to market itself as a standard-bearer of an imperious kind of liberal virtue — how it has convincingly sold itself as the center of the resistance. For many who oppose the president, of course, there would be very little to resist right now if New York City hadn’t incubated and rewarded the ambitions of Donald Trump for so many years. In the service of policy and his own public persona, Mr. Schneiderman was a Trump antagonist generally, and a feminist specifically; in his private dealings with women he was, according to those he is said to have victimized, a sadist. Big City A weekly column devoted to life, culture, politics and policy in New York City. Earlier this week, the actress Annabella Sciorra, one of Harvey Weinstein’s accusers, remarked on Twitter that a while back when she had disclosed that the producer’s spies were still contacting her, Mr. Schneiderman emailed to make sure that she was O.K. This sort of duality, however extreme in Mr. Schneiderman’s instance, is not unfamiliar in American politics. We have been getting schooled in the mechanics of compartmentalization at least since the sex scandals of the Clinton presidency, and we have been given epic refreshers at the hands of New York Democrats. Eliot Spitzer, the father of daughters, frequently called himself a feminist and championed women’s causes and resigned as governor when it was discovered that he was sleeping with prostitutes. Anthony Weiner styled himself similarly, then left Congress over a nasty texting scandal, and moved on to prison when it was found that his habit included sending pornographic messages to teenage girls.

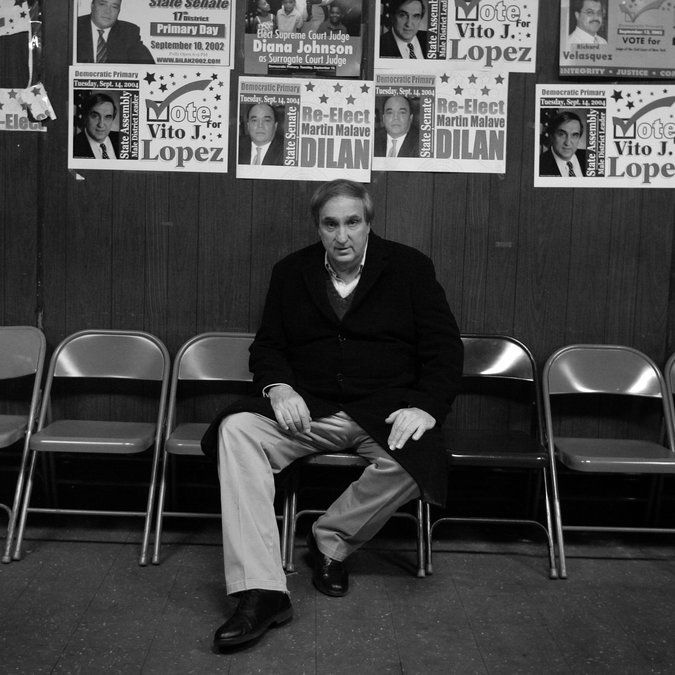

Deborah Glick, a Democrat who has represented Greenwich Village in the State Assembly for 28 years, told me recently that she always felt conflicted about Mr. Schneiderman: He was arrogant, she said, but he was ours. (Mr. Schneiderman had served in the State Senate.) As a longstanding member of the Legislature, Ms. Glick would have, I imagined, worthy insights into the peculiar culture of Albany, which became the state’s capital in 1797 and has distinguished itself 200-some years later as a black hole of sexual misbehavior, harassment and violation. An aggressively edited account would include the cases of Vito Lopez, the omnipotent Brooklyn assemblyman whose career ended after young female aides complained of his compulsive groping and manipulation; Hiram Monserrate, the Queens senator expelled from the legislature in 2010 after he was convicted of physically assaulting his girlfriend; Micah Kellner, a Manhattan assemblyman accused of sexually harassing both male and female members of his staff; Sam Hoyt, an upstate assemblyman who was formally sanctioned by colleagues after a relationship with an intern that had him emailing her with lines like, “I could be your human lollipop”; and J. Michael Boxley, a prominent statehouse lawyer who was charged with raping a 22-year-old staff member after a night of drinking. None of these men were Republicans. Instead of transitioning to a job where he might have been forced to spend his days asking, “Tall or venti?” Mr. Hoyt was given a senior position in the administration of Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo, despite the governor’s feminist pronouncements. Mr. Hoyt remained in that job until last year, when he stepped down as a result of a sexual harassment investigation. Mr. Boxley pleaded guilty to sexual misconduct on the rape charge, eventually landing a job at a major law firm in Albany, after his suspended license was reinstated. In New York, commitments to rehabilitation are highly selective.

The conventional wisdom about what has condemned Albany to such sordidness could be applied to many state capitals in places where legislators are away from their home districts for long periods of time (in the case of New York, it is from January to June) and there is nothing to do but drink in the bars that are near the government offices that are close to the hotels where many people stay. Other state governments have obviously been roiled by scandal amid the national reckoning on sexual harassment. In California last fall, 140 women, including legislators and lobbyists, came forward to protest a widespread culture of misconduct in Sacramento. In Missouri, the governor has been caught up in a scandal over an affair and accusations of blackmail. But in Albany, an absence of term limits for legislators breeds a complacency and has kept in place — let’s call them Legacy Men, those who came of age when the rules about how to navigate office life were very different. And yet youth presents problems of its own. Salaries for legislators are quite low; newly elected members of the Legislature are often young, and for a long time, before standards of conduct were better codified, men in their late 20s would arrive in Albany and see little wrong with dating interns who were 23. “People who have done this from an early age, I don’t know how they keep their feet on the ground,” Ms. Glick told me. “On the one hand, we’re poor shlubs up here, but people are very deferential. You go into a supermarket and its ‘Hello, assemblywoman!’ I walk into a room late, and people ask if I want to be the first one to speak. That dislocates people.” That reverence is at odds with the low regard for Albany in New York City, where apathy, or even disdain, for many aspects of local politics, especially among the wealthy and influential, is pervasive. Were it otherwise, women might fill more than 11 of the 51 seats in the City Council, and voter turnout for those races might not be so dismal. You could spend hours in front of any luxury retail outlet on upper Madison Avenue before you would find a half-dozen people who could name their state senator. Even in more explicitly liberal and engaged parts of the city, in brownstone Brooklyn, for example, you will hear a lot more about congressional races in Pennsylvania and Oklahoma than you will hear about contests happening only several miles away. Currently, in the 11th District, encompassing Staten Island and parts of southern Brooklyn itself, Michael Grimm, a Republican who lost his Congressional seat when he was sentenced to prison on charges of tax fraud, is leading in some polls in a race to reclaim it against a more moderate primary opponent, the never-incarcerated former prosecutor Dan Donovan. Supplementing his profile, Mr. Grimm also once famously threatened to throw a reporter off a balcony. Dismissiveness leads to withered scrutiny (enabled as well by the long retrenchment of the newspaper industry), and that withered scrutiny in turn allows a dangerous prurience to persist. The case of Mr. Lopez, who had long been protected by the former speaker, Mr. Silver, is instructive. Even after the State Assembly censured Mr. Lopez for sexual harassment in August 2012 (one year before he would resign and three years before he died), he won re-election to a 15th term, in a district that includes Bushwick and Williamsburg, where so many millennials negatively disposed to the patriarchy have made their lives. This is “Girls” country.

Leah Hebert, who began working for Mr. Lopez in March 2011, was one of several young women to ultimately file formal complaints against him. A graduate of Cooper Union, she had been living in a loft in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and doing tenants’ rights work as a volunteer. Among his many good causes, Mr. Lopez had pushed through a loft law that allowed tenants living in what had formerly been manufacturing spaces in certain neighborhoods in Brooklyn to remain in them legally and at relatively low cost. Ms. Hebert met him at a party in Brooklyn, and he offered her a job on the spot. “It seemed like a an amazing opportunity to go work for this progressive housing advocate,” she told me. After she worked for Mr. Lopez for six months, he promoted her to chief of staff. The harassment began with the new job title, she said, with vague comments first and then a request that she share a hotel room with Mr. Lopez on a trip to Puerto Rico. When she refused to go, he fired her, but then he hired her right back. “This became a game with him,” she said, “where he would put my job in jeopardy and say, ‘You need to be more personal; you need you to send me text messages and say you care about me.’” She went on: “He was obsessed with me getting my eyebrows waxed. He was obsessed with me getting facials and wearing makeup. I can’t tell you how insane this experience was. He would tell me to flirt with people to get donated turkeys for Thanksgiving for his seniors. At some points I’d think, am I in someone else’s horror movie?”

Once, she confided to him that she had been raped in college, and that his treatment of her was reigniting her trauma. He responded by asking her for a massage. Ms. Hebert is part of a consortium of women, all former legislative aides, who have protested the recent passage of the state’s sexual harassment law, which fails, among other things, to reform the laws around nondisclosure agreements, meaning that certain misdeeds can potentially remain shielded from public view. New York is far less progressive on gender issues than it is in its own imagination. Only 27 percent of members of the state Legislature are female, which puts New York ahead of Wyoming (where the figure is 11 percent) but significantly behind Arizona, which has a 40 percent representation. The Child Victims Act, which would extend or eliminate the statute of limitations regarding child sex abuse cases, has still not passed the New York Legislature. The senate has failed to pass a civil-rights bill for transgender people, at a moment when the Trump administration is trying to roll back protections for them. “Our abortion laws predate Roe v. Wade,” Brad Hoylman, a Democratic state senator representing much of the West Side of Manhattan, said. “So if the Supreme Court overturns Roe, New York could go back to the 1960s.” A few years ago, Mr. Hoylman, the only openly gay member of the Senate, issued a report called, “Stranded at the Altar,” which demonstrates that the state Legislature’s leadership on LGBT issues essentially came to a halt after the Marriage Equality Act passed seven years ago. In the report, he points out that during the 2015 session alone, the Senate passed 1,637 pieces of legislation, none of them addressing the needs of gay, lesbian and transgender individuals. Instead the Senate voted on 19 bills creating distinctive license plates; 32 bills expanding hunting and fishing and 11 bills devoted to ceremonial recognition, including one naming the wood frog the state’s official amphibian. Gay conversion therapy, Mr. Hoylman noted, is still legal in New York.

Progressive hypocrisy has deep roots in New York politics, as it happens. Arriving in Albany in 1882 as a 23-year-old state assemblyman, Theodore Roosevelt quickly found a target in a New York City commissioner, Hubert O. Thompson, who wore diamonds and filled refrigerators with champagne, ostensibly on a municipal salary. Thompson’s office, which oversaw the city’s infrastructure, saw millions of dollars pass through it, and Roosevelt, who essentially created progressive rectitude as a political brand, was determined to ferret out the self-dealing. Nine years later, Roosevelt was trying to get his own brother, Elliott, committed to an asylum to contain what he imagined as a crisis that could thwart his presidential ambitions, the historian William J. Mann has argued in his book “The Wars of The Roosevelts.” Elliott had an illegitimate child with a young German servant whom Teddy was, at the same time, working to silence. “If some frightful scandal arises, it should be widely known that we regarded him as irresponsible,” Roosevelt wrote to his sister. He would let nothing get in the way of his image as an agent of moral protest. Which might make him feel entirely at home in New York today.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.