The Equestrian Coach Who Minted Olympians, and Left a Trail of Child Molestation

By Sarah Maslin Nir

There’s no trace of Jimmy A. Williams, the Show Jumping Hall of Fame trainer, at the equestrian club where he was an instructor for nearly four decades, cultivating young riders, some of whom went on to Olympic fame. The pictures and paintings of Mr. Williams, who died in 1993, and the sterling trophies he won all vanished without a word recently from the clubhouse where he had spent many afternoons tipping back Champagne with some of Los Angeles County’s biggest and richest names: the parents of his young charges. Last month, the club removed his name from the grand show jumping stadium at the heart of the sprawling property at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains, once the Jimmy A. Williams Oval. Today it is just Ring 1. But his former riders cannot forget Mr. Williams. Across the country, in her New Jersey barn adorned with her Olympic medals, Anne Kursinski, one of the country’s most decorated show jumpers, remembered her former coach. How he tasted of alcohol whenever he pinned her in a horse stall and crammed his tongue into her mouth. And far more. “He penetrated me when I was 11,” Ms. Kursinski said, revealing publicly for the first time the details of what she said became six years of continual rape and molestation. “I was a little kid,” she said. “And he was God.” The equestrian community has been rocked by the revelations of abuse made by Ms. Kursinski and four other students, the broad strokes of which were first reported last month by The Chronicle of the Horse, an industry publication. It has shaken an insular universe in which Mr. Williams, in life and after, was a mythic figure, revered for his knack with difficult horses and for churning out top-flight riders.

But few have been surprised. Interviews with 38 former students, trainers, grooms, equestrian officials and members of the Flintridge Riding Club reveal a rarefied social scene in which Mr. Williams groped and kissed young girls publicly and with impunity — though few knew the true extent of the abuse. They describe a toxic brew of prestige and ambition that led parents, bent on their child’s success in the show ring, to ignore his near daily predations — and persuaded children who were afraid of losing beloved horses to stay silent. What emerged was a world where, for adults, entree to cocktail hour in the Spanish Colonial-style clubhouse and access to a man with movie-star good looks and a legendary way with horses seemed to eclipse whatever it was rumored to have happened back at the barn. “The unspoken rule was of not saying anything, not divulging anything,” said Karen Herald, 58, who rode there from age 16 to 20, during which time she said Mr. Williams continually molested her. Mr. Williams wielded carrot and stick to ensure silence, she and others said: better horses to ride for those who were compliant, and threats they’d fail in the sport without him as coach. “For the riders, it was, ‘Oh my God, I want to be the best rider,’ ” said Ms. Herald, who now works in breast cancer research. But for the parents, she said, “It was, ‘Oh my God, I want to be a part of this.’ ”

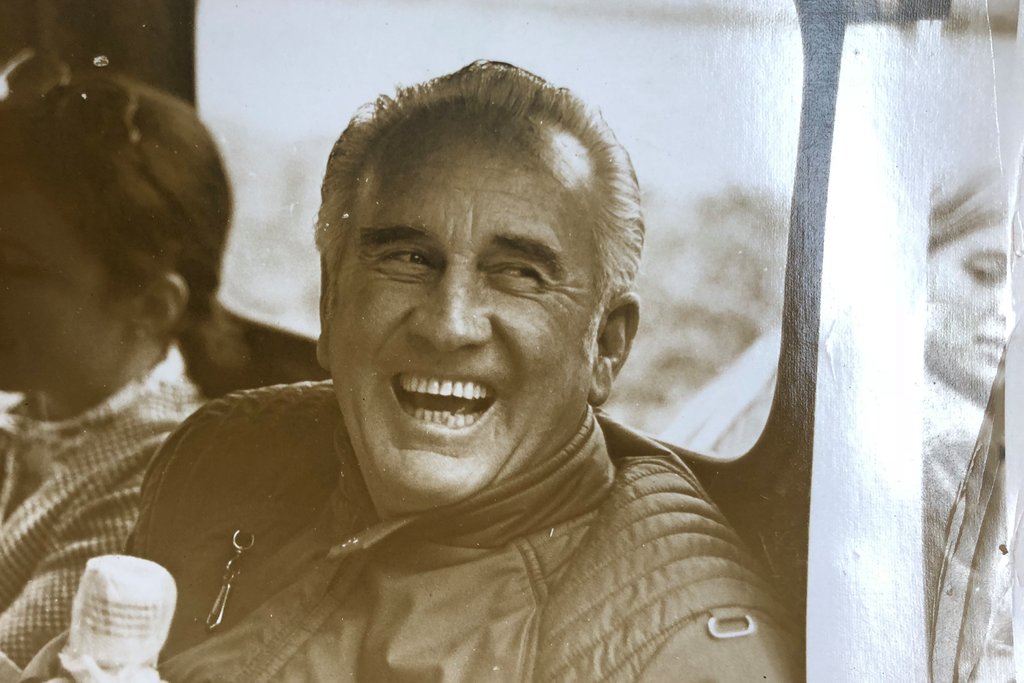

‘Such a Vague Rumor’ Mr. Williams, who died at age 76, zipped around horse shows in a cowboy hat and a cloud of cologne in a customized golf cart emblazoned with the phrase, “Jimmy Williams is a clean old man, amen.” He was a World War II veteran who learned classical riding when stationed in Italy, according to multiple biographies. He left military service with a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star with valor to return to California, where he starred in several movies as an equestrian stunt double. Handsome and spouting aphorisms, he was known as a ladies’ man; an obituary in The Los Angeles Times said he was married six times. He began riding at 8 years old, with stints in almost every discipline, from racehorses to Western horses, according to the National Reined Cow Horse Association, where he is in the association’s hall of fame. He began working at Flintridge in 1956, and remained employed there until his death. As Mr. Williams climbed in prestige, netting accolades and even the establishment in 1988 of a lifetime achievement trophy in his name by the sport’s top governing body — his trademark cowboy hat in silver by Tiffany — the whispers that escaped the paddocks of Flintridge were ignored. Just before the trophy was inaugurated, Jane Forbes Clark, then the first vice president for the sport’s governing organization, was warned of Mr. Williams’s rumored misconduct, she said, by a person she declined to name. But Ms. Clark did not investigate the veracity of the story other than to call a friend, Frank Chapot, the six-time Olympian, who died in 2016, and ask for his opinion. Mr. Chapot’s wife, the Olympian Mary Mairs Chapot, had trained with Mr. Williams. Ms. Clark did not speak to Mr. Williams or any Flintridge clients, or raise the issue with her board, Ms. Clark said. “It was such a vague rumor,” Ms. Clark said. The trophy was unanimously adopted by the organization.

Two years ago, the organization caved to back-room pressure exerted by Ms. Kursinski and other victims to remove Mr. Williams’s name from the lifetime achievement trophy. But at the time, Chrystine Tauber, then the president of the United States Equestrian Federation, did not disclose the reason. In a 2016 statement, Ms. Tauber said it was a purely bureaucratic decision. Only last month did the federation reveal the truth, after being pressed by a reporter from The Chronicle of the Horse. When asked by The New York Times why Ms. Tauber had obfuscated in 2016, the federation issued a statement correcting the record: “We did what we believed was responsible at the time to protect any potential victims, as we did not have a substantiated claim of sexual abuse,” Bill Moroney, the chief executive of the federation, wrote in an email. “Our public statement has changed and the Jimmy Williams trophy has been retired due to the substantiated allegations from a victim with whom Jimmy Williams engaged in sexual misconduct during his role as her trainer.” Why it took decades for the allegations to surface is something that the victims struggle to understand. Many themselves said nothing. “I think it must have been because he was Jimmy Williams,” said Susan Lomenzo Langer, who rode there when she was 15. “For Jimmy Williams to invite you to his house even if it was to chase after you and corner you and molest you. He was a magician with horses; we were so in awe of him. “He was so famous, he was a movie star,” Ms. Lomenzo Langer said, her voice rising with emotion: “I was a kid!”

‘He Was a Great Horseman’ Some dispute the allegations against Mr. Williams. Susan M. Hutchison, a professional grand prix rider, began riding at Flintridge Riding Club when she was 5. When she was 18, she began living with Mr. Williams, who was then 55. The long-term partnership continued to his death, according to his obituary in The New York Times. Ms. Hutchison has vehemently denied any abuse, and denounced the accusations in published reports. She declined a request to comment for this article. Of the 22 club presidents over the course of Mr. Williams’s long tenure at Flintridge, almost all are deceased. Priscilla M. McClure, who served as president from 1977 to 1979, said that although she knew that “Jimmy kissed everyone indiscriminately,” not a single person had ever complained to her about Mr. Williams’s conduct. “It would have been my responsibility as president to look into such allegations,” she said. “I believe every one of them, but I didn’t hear anything from any of them, and I didn’t hear anything from parents,” she said. “Perhaps that was because people knew that I regarded Jimmy as a friend. I would have been the last person anyone would have come to about that.” Alan F. Balch, a president of the club during the 1980s and 1990s, who at the time of Mr. Williams’s death was writing his biography, according to The Los Angeles Times, did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. In an extensive statement to The Chronicle, Mr. Balch said he heard of only a single incident: A former member called him on behalf of her daughter and another girl, whom he declined to name. He detailed confronting Mr. Williams, who denied the accusations and indicated that competitive equestrian rivalries spurred the claims. “It seemed to me that she, her daughter and Jimmy needed to make peace about all this among themselves, and I said so,” Mr. Balch said, according to The Chronicle. “Only they knew the whole truth about the matter.” He added, “Jimmy Williams never claimed impeccable personal virtue.”

The president of the Flintridge Riding Club, Suzanne Osimo, did not respond to messages or emails requesting comment. On April 18, club members received a letter stating that given the allegations, the club would “remove from our publicity the affiliation with him.” Several people contacted for this article said that while they had seen Mr. Williams kissing and groping students, they attributed his behavior to social mores of a different era, rather than any nefarious intent. Many expressed anger that Mr. Williams was not alive to defend himself against the allegations and that the legacy of an important and talented horseman had been tarnished. “It’s sad things like that are said about a man who has been passed away” for more than 25 years, said Hap Hansen, who grew up riding at Flintridge and became one of the most successful grand prix riders in the world. While he said he witnessed Mr. Williams kissing and touching women and girls, Mr. Hansen said he did not believe it was without consent. “I think he was a great horseman; he was a legend in his time,” Mr. Hansen said. “In my mind, he still is. I just think those things are stupid to bring up whether they are true or not.” Avoid the Barns Even for the few children who spoke up about the misconduct as it happened, Mr. Williams’s status as an equestrian giant served as a de facto silencer. Ringside at the Indio National Horse Show in Indio, Calif., in 1968, Mr. Williams scouted 14-year-old Melissa Cardenas, now Mihalevich, a high-jump prodigy, pitching to her mother that Melissa should train with him. After the adults struck a deal, Mr. Williams followed her to where she was grooming her horse, High Barbaree, Ms. Mihalevich said, threw his arm over her in an avuncular way and then shoved his tongue down her throat.

She ran and told her mother. “She just could not believe that,” Ms. Mihalevich said. “It was Jimmy Williams.” The plan to train with Mr. Williams went forward, and lasted three years, she said. So too did the abuse. For Ms. Kursinski, who for decades after the abuse ended continued to champion his horsemanship in interviews, her silence stemmed in part from a sense of gratitude for his role in helping her toward equestrian superstardom, she said, a duality she has tackled through therapy and spiritual work. “At one point I felt there were almost two of me,” she said. “There’s this little thing over here, and there is this other part of me that rides. To survive.” She added: “I still have to say he is a genius. But he was sick.” Mr. Williams’s modus operandi, several students said, was to corner them in horse stalls where he would push his tongue into their mouth or force their hands down his riding breeches. They quickly learned to avoid the barns, they said.

Mr. Williams lived on the club property in a bungalow beside a riding ring, behind a high hedge that circles the house like a moat. When Ms. Gaston was 17, he summoned her inside, pulled her head down and pressed her mouth to his exposed penis, she said. She screamed and her braces scraped his genitals, she said; when he recoiled, she escaped. Ms. Gaston told several adults, who confronted Mr. Williams that night, but she was unsure if the club was ever notified. “Everyone always turned the other cheek,” Ms. Gaston, now a filmmaker, said. “It was a system.”

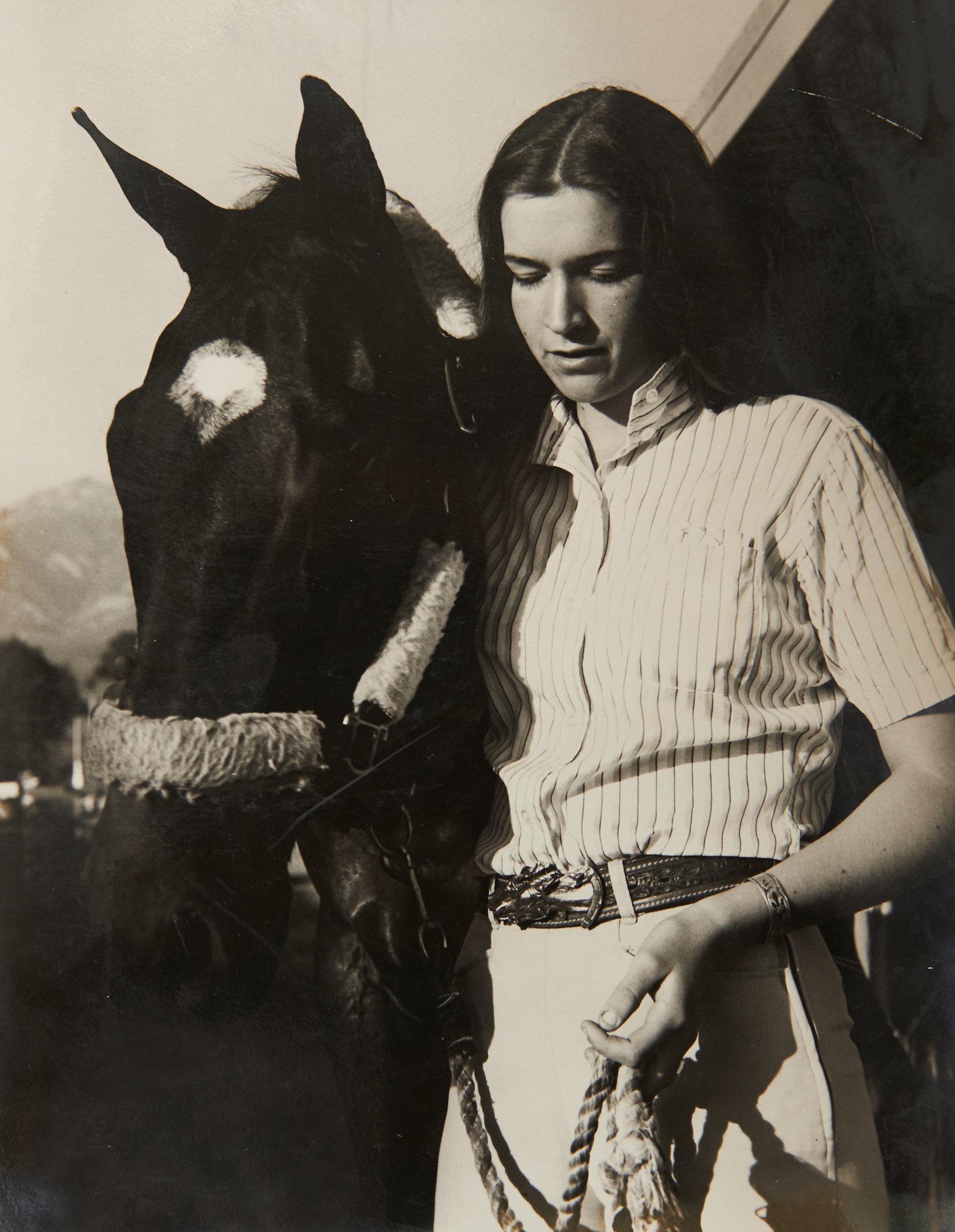

In the early 1990s, Francie Steinwedell-Carvin, a grand prix rider and former student of Mr. Williams’s, and Ms. Kursinski confided in each other for the first time. They had ridden together as teenagers, and, along with a few others, unearthed old rosters of riders from Flintridge and began calling down the list, asking whoever picked up what she had experienced. On a spring day in 1993, five former students of Mr. Williams’s gathered in a small bungalow by the beach in Santa Monica. They had ridden together as girls: Ms. Gaston; Ms. Herald; Ms. Steinwedell-Carvin; and Ms. Kursinski and her sister Lisa, who has since died. They gathered for a group-therapy session with a therapist and shared how each had been preyed upon by Mr. Williams. For Ms. Steinwedell-Carvin, 57, who has battled addiction, it was the beginning of understanding memories — of Mr. Williams forcing her to touch his penis and inserting his tongue in her mouth as a child — that she had long pushed away. And her need to silence her sense of shame with alcohol and drugs. “I learned what was yanked away from me because of the abuse,” she said. Standing at Middle Ranch, eucalyptus-shrouded stables 15 miles northwest of Flintridge Riding Club, on a recent day in May, Ms. Steinwedell-Carvin stroked the muzzle of Bandolero H, her chocolate bay horse.

“I kept everything in for so long,” she said. “I wanted to hide, but what I really wanted was someone to find me and put their arms around me and say, ‘It’s O.K., you’re going to be fine.’ That’s what the horses have done for me.” On May 14, the United States Equestrian Federation barred Jimmy A. Williams from its membership — 24 years 6 months 14 days after his death. Correction: May 30, 2018 An earlier version of this article referred incorrectly to when Alan F. Balch was president of the Flintridge Riding Club. He was president in the 1980s and 1990s, not the 1970s. Susan C. Beachy and Jose A. Del Real contributed research.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.