The ‘sex Cult’ That Preached Empowerment

By Vanessa Grigoriadis

One winter morning in a conventional suburb outside Albany, N.Y., Nancy Salzman, the 63-year-old president of a self-improvement company named Nxivm, sat on a mahogany-colored stool in her kitchen. Her tasteful home was surrounded by other Nxivm members’ modest townhouses or capacious stone mansions that seemed to spring up out of nowhere, like mushrooms, on the suburban streets. In Salzman’s den, a photo of her with her two adult daughters hung on a wall, the three of them wearing smiles as wide as ancient Greek masks of comedy; the same happy photo served as the wallpaper on Salzman’s laptop. A hairless Sphynx cat prowled the lovely buffet of croissants and fruit on her kitchen island. Salzman, an extremely fit woman wearing the type of thin athleisure sweatshirt that’s all the rage with the middle-aged bourgeoisie these days, turned her attention to a woman sitting at the island: Jacqueline, a 27-year-old with long dark hair, who was a psychology student in college, told me that she hadn’t experienced anything as effective as Nxivm (pronounced “nexium,” like the heartburn medication). Like Scientology’s L. Ron Hubbard, whose 1950 handbook “Dianetics” was billed as the “modern science of mental health” and whose pseudoscientific methods were, in his view, world-changing, Keith Raniere, Nxivm’s 57-year-old founder, believed his organization could heal individuals and transform the world. The way Nxivm did this was through techniques, or “technology,” meant to rewire your emotional self. Salzman, who has training in neurolinguistic programming, which involves hypnosis and techniques of mirroring another individual to create deep rapport, was about to embark on a therapy session in which she would ask Jacqueline to cast her mind back to her childhood, as Nxivm sessions often do. Jacqueline had come to her with a phobia: She flips out when she gets on a plane. One time, she had to get off an airplane that had boarded because she became nervous, and when she wanted to get back on, the flight attendants wouldn’t let her. Salzman nodded. In a near whisper, she asked Jacqueline a stream of intimate questions not only about her fear of flying but also about her parents’ relationship. She ascertained that Jacqueline believed her mother was ill used by her father, who forced the family to move often, by air. “It was always gray around her,” Jacqueline said sadly, of her mother. “She had a horrible life.” But at the same time, she said, her upbringing made her feel as if she always needed a man to protect her. Listening to Salzman’s questions, it became clear that she was positing that these issues — Jacqueline’s fear of flying; her belief that her mother was forced into a terrible life by her father; and her inability to be an independent woman — were connected. We are controlling our own lives all the time, Salzman said. We are all in complete control. Jacqueline’s mom had been in control but had chosen to be a victim. And Jacqueline was in control and had chosen to be a victim, too. “Are you pretending to be a helpless woman?” Salzman said earlier. “That’s the way I receive attention, that’s kind of my thing,” Jacqueline said. “Women are allowed to be dependent on men,” Salzman explained. “A great part of being a woman is no matter how you screw up your life, you can always move back in with your dad. Every time you have chosen to stay dependent, you have made a decision not to be independent.” What if she became the person she relied on? Within half an hour, Jacqueline had “upgraded” her belief system; closing her eyes, she said the tightness in her chest that she typically got when she thought about flying was gone. She also agreed to do one thing that terrified her each day for the next 30 days, and on a day when she indulged in a man’s attention, she would do two terrifying things. Facing your fears, especially in conjunction with penance, was key to Nxivm. As Jacqueline prepared to leave, the two women hugged. “I don’t know what happened,” she said. “I feel really good.” The scene in Salzman’s home was intense but mostly cheery. Yet last October, The New York Times published an article reporting alarming practices by Nxivm. The article explained that some female members of the group, who called themselves “masters,” had initiated other women, calling themselves “slaves,” into a ritual of sisterhood at homes in and around Clifton Park, near Albany. First, they stripped naked. One by one, they lay on a massage table while a female osteopath, also a Nxivm member, used a cauterizing pen to brand the flesh near their pelvic bone. She carved a symbol that some women thought represented the four elements or the seven chakras or a horizontal bar with the Greek letters “alpha” and “mu,” but if you squinted and looked again, contained within them a different talisman: a K and an R — Raniere’s initials. Not all the women were told that these initials were present in the symbol. Hundreds of members fled Nxivm after they learned about the branding, but much of the inner circle remained. Citing the fact that Raniere had a cast of girlfriends, the media declared that Nxivm was not a self-improvement company at all but rather a “sex-slave cult.” A federal investigation was opened, culminating in Mexican police officers plucking Raniere from a pricey villa; he is now in a federal jail on the Brooklyn waterfront after being denied bail as a flight risk. Another Nxivm member, Allison Mack, a blond actress who played Clark Kent’s friend on the long-running “Smallville,” was arrested and later released on $5 million bail. Raniere and Mack were charged with sex trafficking and conspiracy to commit sex trafficking and forced labor. Federal agents also raided Salzman’s home, seizing $523,000 in cash, some of it in shoe boxes. (She has not been charged with a crime to date.)

The group found itself under a microscope, its secrets exposed. Some members came from the highest reaches of society, forming a kind of heiress Illuminati. There were two daughters of Edgar Bronfman Sr., the former head of the Seagram Company; Pamela Cafritz, who died in 2016, the daughter of political donors Bill and Buffy Cafritz; a number of well-to-do Mexicans, including Emiliano Salinas, the son of the former Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who has since publicly disavowed Raniere but remains affiliated with the group, and Rosa Laura Junco, the daughter of the president and chief executive of the newspaper publisher Grupo Reforma; as well as prominent TV genre actresses who discovered Nxivm on location in Vancouver, including Nicki Clyne from “Battlestar Galactica” and, of course, Mack. These puzzle pieces formed the ultimate tabloid story in an age of the vast tabloidification of media, and a tale about female empowerment and lack thereof in a time of feminist uprising, laced with questions of consent and coercion wielded by a man of power without accountability. Some women were severely thin, possibly as a means of mind control. Key defectors began speaking out. “We were both upset,” Sarah Edmondson, a former leader of Nxivm’s Vancouver chapter, wrote by email recently about why she and her husband left after a decade in the organization. “And disgusted. About the brand and a lot more. Nothing was what we thought it was.”

From inside the group, all this looked very different. “Come on, man, this sounds like a bad horror movie,” a member named Eduardo Asunsolo told me incredulously about the recent media coverage. Since the group’s founding in 1998, it has been a tightly knit organization, “like a family,” as Raniere has described it. About 17,000 people have come through Nxivm’s doors, though the number of those who have committed for life was far smaller, perhaps in the hundreds. (By comparison about 25,000 individuals in the United States are self-identified Scientologists.) Members believed that Raniere could heal them of emotional traumas, set them free from their fears and attachments, clear patterns of destructive thinking. Some believed he could heal them sexually too. “This is the white-collar spiritual path,” an ex-member says. “You’re on the monk’s path, but you’re not wearing a red robe with a shaved head.” [Read more about the secretive group Nxivm] Raniere presented himself as a great philosopher, an ethical man and a scientist pushing the bounds of human capability. He had not only devised classroom-based courses that lasted as long as 12 hours a day for 16 days — recalling the Landmark Forum, a group-therapy company that has its origins in the 1970s consciousness-raising seminar EST — but also advocated that his followers control habits of mind and body, like food and exercise. He also seemed to have a unique, pulsating idea that resonated with women, particularly wealthy ones. This was an intersection of theories about femininity, victimhood, money and ethics, much of it influenced by Ayn Rand, one of Raniere’s favorite authors. The ultimate Nxivm member was “potent,” in Nxian lingo — not only rich but emotionally disciplined, self-controlled, attractive, physically fit and slender — or, in the word most members themselves preferred, “badass.” Much of today’s upper class is engaged in a frenzy of self-improvement. They want to be skinnier, healthier, younger-looking, smarter, nicer, more loving and, since Trump assumed the presidency, more politically aware too. But were they truly improving? They may eat more vegetables, but this age seems more narcissistic than any before, more beholden to snake oil, and has put many individuals in the grip of an uneasy self-image toggling between unrealistic grandiosity and soul-crushing envy. Nxivm positioned itself as the true self-improvement gospel. As I observed in Salzman’s kitchen, its core tenet was wildly optimistic. Members believed that humans can alter our emotional triggers and our beliefs about ourselves, particularly those formed in childhood. We don’t need to be angry because our mothers withheld love; or selfish and self-protective because we were bullied in school; or fall in love with people who bestowed gifts upon us because we loved a grandmother who did. The unexamined among us allow these ancient self-perceptions to run the show in current time, but not Nxians. They “integrate” these experiences in intense, hypnotic, secret-telling sessions like the one I saw called Explorations of Meaning. In an E.M., you often “explore the meaning” of a memory and observe the misperception that has made it painful, thus reducing the power that the memory holds over you today. “It’s the most potent way to deconstruct an emotional trigger” and permanently change the way you process it, a former member told me. Experiencing integration after integration, the Nxian feels light, buoyant and more powerful than before. “We are just trying to create joy,” another member said. Breaking down identity was only the first part of Nxivm — replacing your identity with another, or “replacing data with data,” in Nxivm speak, was the second part. As Nxians erased their fears, they began doing what they truly wanted to do with their lives (or perhaps what Raniere or high-ranked members wanted them to do). I talked to a banker who remade himself as an actor. I talked to a diversity specialist at a Connecticut boarding school who decided she wanted to start a farm. India Oxenberg, a daughter of the “Dynasty” actress Catherine Oxenberg, spoke to me about taking courses taught by the group in Los Angeles. She wanted to feel closer to her friends, boyfriend and family, whom she often felt like pushing away, whom she felt “not to use such a harsh word, but so repulsed by. Why can’t I just be in the same room with my family who I love but at the same time I want to crawl out of my skin and run away?” After she took Nxivm courses, she said she realized that “I’m the one who is choosing to feel bad about the situation.” She also decided that she didn’t want to be in the entertainment business. She wanted to be a caterer. Oxenberg moved to the Nxivm motherland, Clifton Park, to “focus on my growth.” She signed up for the group’s “university,” which can reportedly cost $5,000 a month. Raniere’s courses largely teach neurolinguistic programming techniques and introductory ethical and psychological theory, which students are encouraged to understand in the context of their own lives. Oxenberg took courses like Mobius, about healing the parts of yourself that you reject and not hating them in other people; and Human Pain, about understanding that love and pain often go together. Nxivm taught the power of penance as a time-tested shortcut to achieving self-improvement. Oxenberg took long walks alongside Raniere, her guru, to discuss her goals. He encouraged her to start her own business, and she did, calling her catering company Mix, because it was a mix of vegan, vegetarian and Mexican food. When she was done cooking, she delivered meals through suburban developments in a BMW. Many members and ex-members of Nxivm that I spoke with — most of them fans of science and math, funny and strikingly perceptive — agreed on one thing: The “technology” worked. Raniere could program you. He had solved the equation of how to be a joyful human. Decide on your ethics and make them the guiding force in your life; do not make decisions that are not in line with those ethics. Look to create strength and character through discipline. Look to create love. Do not reject your family (unless your family rejects Nxivm, in which case some other steps may be necessary). Do not be a slave to your fears and attachments. Pain creates conscience; do not be afraid of pain. Nxivm had not granted access to a journalist for an article for 14 years before it gave me a tightly stage-managed tour of its leadership and operations this winter, ahead of potential indictments. It remains highly secretive and exquisitely paranoid. Members not only tape-recorded my interviews with them but had a practice of extensively taping or video recording within the group, including documenting many of Raniere’s statements. They have also answered some defectors, journalists and critics with lawsuits. A New Jersey-based lawyer, Peter Skolnik, who represented the author and noted cult deprogrammer Rick Ross in a 14-year suit with Nxivm, told me that he estimated their cost of the suits at $50 million. My initial contact within Nxivm was Clare Bronfman, one of the two Bronfman daughters who are staunch supporters. To meet her, I traveled to Mexico, where Nxivm had built educational centers and where she was staying with Raniere, in an urban location I was asked not to reveal. This was a fancy neighborhood of gated homes and German cars and builders’ cranes creating more expensive apartments. They were staying there on the advice of lawyers and consultants and also because Bronfman was fearful in the United States. She was fearful here in Mexico, too, worried that someone connected with a disgruntled ex-member or someone who had read about her wealth might kidnap her when she was out for a jog. Bronfman was wry and slight, polite. We met at one of Nxivm’s midcentury-chic Mexican centers, behind a gate. She walked its airy halls, gesturing to the room where they keep their instructional materials (with a keypad lock on the door), a framed photograph of Raniere hanging on one wall and a stenciled quote from him on another — “If in the next moment your behavior would affect all of humanity for forever more, how would you behave? Every moment is such a moment.”

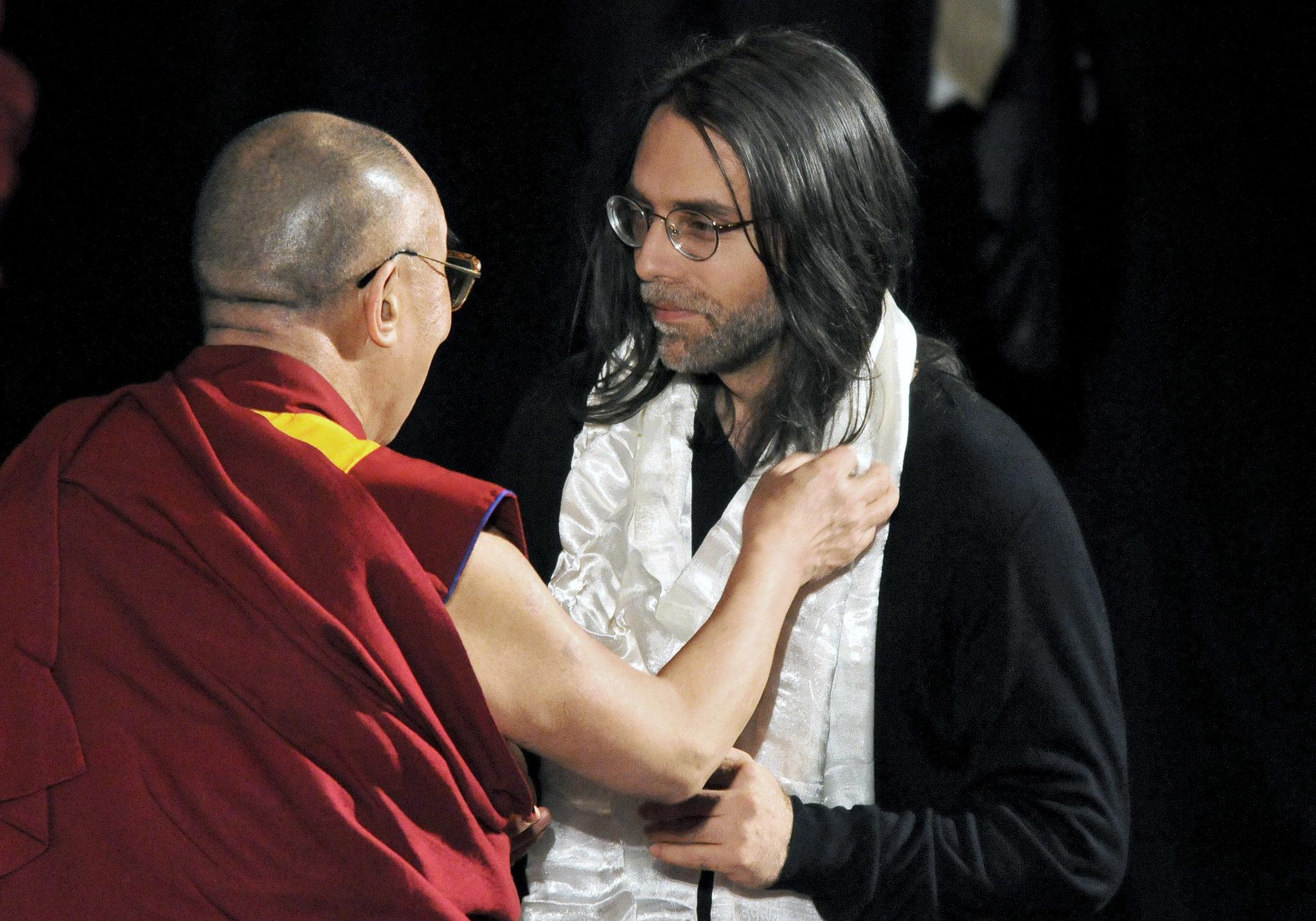

She took a seat on a cozy couch, set up for intimate chats among members. Bronfman told me she was an introvert, and her voice was so soft that it drifted away, but she answered my questions directly and seemed highly in touch with her emotions. The only jewelry she wore was one of Tiffany’s most famous pieces: a silver outline of a heart, dangling on a delicate necklace chain. She told me that she had shared a handful of necklaces with the women in the group when they were on vacation on an island she owns in Fiji, just months before Cafritz, a bubbly woman who was Raniere’s most important long-term girlfriend and a beloved mother figure to Nxivm members, died from cancer. Bronfman began crying as she told me about her friend’s death. Bronfman outlined the shape of the group for me. Raniere was called “Vanguard” because he was the leader of their philosophical movement. Salzman, his first student, was “Prefect.” Bronfman and everyone else were students of Vanguard’s. Centers like this one were the place for Nxivm courses, though they weren’t taught by Raniere, who had “duplicated” himself when he made Salzman headmistress. Nor were they often taught by Salzman anymore, but rather by members she had instructed, members whom those members had instructed, and so on. All were told not to deviate from Raniere’s blueprints. Nearby, a number of colorful sashes hung on hooks. Each color in the hierarchy was not only a higher state of self-awareness but also reflected a member’s ability to recruit more members. Some higher-ranked sashes have never been attained, Bronfman whispered. You don’t trade up directly to a new color of sash but first must get four silk stripes ironed onto your existing sash, a process known as “moving up the stripe path.” The rigid hierarchy and doctrinaire teachings pushed members to revere those with a higher level of sash, to whom they were encouraged to pay tribute in words and deeds. Anything in the group about skinniness, about punishment, about self-denial was simply to help members evolve. “If something’s uncomfortable for us emotionally, we choose to smoke, we choose to drink, we choose to eat, we choose to dissociate,” Bronfman told me. “We have so many strategies.” The purpose of Nxivm was to “feel those things so that you can work them through and then they’re not uncomfortable anymore.” I thought I was meeting Bronfman before I met Raniere because Raniere liked to sleep late. But after talking to ex-members, I learned there was a pattern within the group of not allowing people to meet Raniere before a Nxivm member, usually a woman, had spoken of his great gifts. Raniere, whom members have compared to Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, didn’t step from behind the curtain until he had been properly introduced. Bronfman and I had lunch together at a local restaurant, though she didn’t eat because she didn’t like the vegetarian options. Then we arrived at a nondescript condo building. Pushing open a heavy wood door, I was greeted by a tall woman with surging dimple creases wearing the Tiffany necklace. She wasn’t authorized to speak to a journalist, so she quickly departed. When Raniere materialized — waking from a micronap — it was as if a record skipped. He was built like a wrestler and dressed in business casual: a sky-blue polo shirt, gray slacks and round tortoiseshell glasses. He was graying at the temples, but the rest of his dark hair was cut with flair and volume. He spoke in a nasal, New York-accented voice and often tossed his hair, a feminine gesture that he used to punctuate his thoughts. He didn’t seem like a man who could make other people orbit him like moons. He seemed like a high-end real estate broker trying to come off as friendly but anxious about closing a sale. “It’s quite a point in life for me,” he said, his eyes somewhat lost behind his glasses. “I question my values, how I conduct myself, all of these things.” He later added, “I don’t think I’m seen as the person I think I am, and I also want to be the person that I think I am.” Those lines portended some grand finale. And Raniere, who seemed intelligent and intensely sad, broke into tears several times, particularly when talking about Cafritz’s death. He was honest about the fact that he was polyamorous and spoke to me about the importance of not only sex but intimacy. But what was important to know about him was that what he does every day is simply walk and think, he told me. He walked 14 to 20 miles a day, calculated by a Fitbit on his wrist, and during those walks, he thought about how to solve humanity’s problems. “I’m like a nerd who has read too much, only I’ve thought too much.” In Nxivm, the point of integrations was reaching what they called “unification.” I asked Raniere later if he was unified. “That’s more a theoretical or goal state,” he told me, adding, perhaps coyly, “I don’t think if someone was unified they would particularly talk about it.” Yet through many hours of conversation, Raniere did not progress to new points. There were some light spots, like when he told me that humanity needed to develop more humanity, and we deserved to, because we were a special species; cats don’t have “catmanity,” he said. But I watched as he drew into himself, seemingly intentionally, becoming a black hole of anti-charisma. In a slow, calm, metronomic voice, he emitted sentences about scientific and philosophical theories: whether humans are biological robots or have free will; whether mysticism is inherently bad or “a tool of understanding but is often abused”; how to interpret Zeno’s dichotomy paradox, a classic logic problem; the possibility that interrelationships with families and friends persist in the afterlife. Raniere has considered himself special for a long time: He has said he spoke in full sentences at a year old, read by 2 and taught himself to play concert-level piano at 12, the same year he learned high school math in 19 hours. His home life was something quite different, and he claimed this was what had led him to create Nxivm. His mother had a heart condition and was often in bed. She and his father fought. About the rancor, he said, “I didn’t blame myself for causing it, but I didn’t know why I couldn’t stop it.” His parents divorced when he was 8, and as an only child, he said he became his mother’s “sole caregiver.” She died when he was 18. Relationships outside his family became of paramount import to him. Raniere graduated from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., with a triple major in biology, mathematics and physics. He wanted to be an academic, but for a child who felt out of control, control of others may have been appealing, and he became interested in the science behind multilevel marketing. His first entrepreneurial foray was called Consumers’ Buyline, which sold groceries and other goods at a discount to those who signed up for memberships. It was enormously successful, at least at first. Local papers in Albany portrayed him as an eccentric, appealing genius, noting that he slept only a few hours a night and could juggle and unicycle. Several years after its founding, Consumers’ Buyline was investigated by state attorneys general as a suspected pyramid scheme, and Raniere and his associates agreed to close shop in 1997. The structure of Consumers’ Buyline brings to mind Nxivm’s setup, with members recruiting other members and the way that Raniere was often introduced late in a participant’s membership, standing out of reach at the top of the pyramid. It might be surprising that people would sign up for a self-improvement endeavor led by a man who might have led a pyramid scheme, but today in Nxivm, leaders explain to incoming members that Consumers’ Buyline had been unfairly targeted, but Raniere refused to be vengeful and instead conceived the group as “an opposing thing that would be good in the world,” as one member told me. After developing another company — a health network selling vitamins and dietary supplements and recommending alternative doctors — with his girlfriend of the time, Toni Natalie, Raniere began thinking more deeply about persuasion and how you could talk people into anything, even helping themselves. When Raniere met Salzman, who had a successful therapy practice near Albany at the time, they began having conversations, just two people going back and forth talking, and soon, Salzman said, she started to feel better, more joyful. She asked Raniere if she could watch him do his persuasion model. “He said, ‘On a person?’ And I said: ‘Yeah, on a person. Can I watch you do it on a person?’ And he said, ‘You mean other than you?’?” She lowered her voice for dramatic effect. “In that moment, I went, ‘Oh, my god, I do feel good.’?” Like Raniere, the Bronfman sisters were seeking to heal familial relationships, particularly with their father, a pillar of New York society and president of the World Jewish Congress. They were also drawn to Raniere’s emphasis on ethics. “My whole life growing up, I always wanted to do something to impact the world,” said Sara, a lovely woman who made me eggs in her Albany-area mansion this winter — the proportions of her home were so preposterous that I felt I had shrunk to a hundredth of my size, like Alice after she drank the potion in Wonderland. “My dad, as we were growing up, he was bringing Jews out of Russia, he was taking on the Swiss banks.” After a friend from Sun Valley recommended the group, then called Executive Success Programs, to Sara, she asked Edgar to take a course, and he liked it. “All my dreams of saving the world with my dad were coming true,” she said. When Clare, who was a professional equestrian competitor in her early years, took her first course, she was unimpressed. Then she listened to Raniere’s theory about money. Like Ayn Rand, he taught that money isn’t inherently good or bad: It simply is. “I thought that money made people bad,” she told me. “When I was at horse shows, I would spend time with people who didn’t have money. I would never connect with people who did.” But she began to realize that “money’s money. And people are people. So rich people can do good and bad, poor people can do good and bad.” Before Nxivm, Clare didn’t deal with her finances. As a wealthy woman, it was all done for her. “My family had lawyers. My family had accountants.” A profound rift developed between Edgar and his daughters a few years into their involvement in Nxivm, but Clare continued to want to use her inherited money ethically. Raniere, like Rand, taught that dexterous use of money — the assigning of value to various goods and services — was one of humanity’s highest virtues. Raniere told me money was “noble.” But after the Consumers’ Buyline debacle, he was careful not to put his hands on much of it himself. In fact, Salzman owns Nxivm, and Raniere has nothing to do with it, officially. He received no salary from Nxivm, nor possessed a credit card, A.T.M. card or a car. He told me, “I don’t pay taxes because I live under the poverty level.” I asked him where he got his clothes, which require money to buy. He answered that they usually appeared. Pointing to the polo shirt he was wearing, he said, “until I put this on this morning, I don’t think I’d worn it before, and I didn’t know about it.” In 2010, documents from a lawsuit stemming from a real estate dispute claimed that many millions of the Bronfman fortune had been spent in connection with Nxivm, and Raniere had also lost nearly $66 million betting on the commodities market. (Raniere insists it was less.) When I asked Raniere about his relationship with Clare Bronfman, he said only that she’s “so supportive, so pure.” With access to Bronfman funds, Nxivm engaged in all manner of legacy-creating enterprises, many demonstrating kindness and concern for others. The group invited the Dalai Lama to Albany, though he initially canceled his 2009 trip after the press drew attention to the mysterious nature of the group; several members traveled to Dharamsala to smooth things over. They’ve designed a “peace pledge” for Mexicans and made a film about Raniere’s ideas to solve violence in the country. They formed an a cappella group named, appropriately enough, Simply Human. They host “Vanguard Week,” an annual celebration of Raniere’s birthday, running triathlons and solving Rubik’s Cubes. Through the year, they played volleyball, Raniere’s favorite sport, usually after 9 p.m., when he preferred to play.

As the group opened centers in New York City, Vancouver and, strikingly, Mexico’s big cities, including Mexico City, Monterrey and Guadalajara, it became more certain than ever about the power of the tech. The day before I met Jacqueline, Salzman introduced me to an 18-year-old high school student she was trying to help surmount Crohn’s disease through Nxivm’s technology. Bronfman has also produced a film about Nxivm improving the symptoms of Tourette patients, which screened at the Newport Beach Film Festival this spring. Raniere had free rein to indulge his interest in scientific experiments. He conceived a new type of school to teach children as many as eight languages at a time; each teacher speaks one language, on the theory that children pick up language more easily from a beloved caregiver. I visited one of these Mexican schools in a pretty stucco building, though school wasn’t in session, so I couldn’t gauge the children’s octolingualism. Nxivm members also created and operate The Knife, an active website that uses “scientific analysis” to gauge the relative honor of news outlets like this one. News was disinformation that could encourage fear, start wars and convince people of anything, but the Knife wielded its powerful tool nobly. The site and its editor in chief were featured last July on “Fox and Friends.” Women filled many high ranks in the group, so it is not a surprise that one of its enterprises involved gender relationships. In 2006, Raniere created Jness, a “made-up word that we are defining as we define who we are,” a female member told me. Some of its teachings seemed reasonable enough: In the beginning of the course titled Raw, men and women were encouraged to talk about their gender’s genuine experience of life, and sex, and how the other sex often made them feel repressed, denigrated and ashamed. By voicing these feelings, which can be taboo to speak out loud, men supposedly developed compassion for women, and vice versa. Jness cost $5,000 for each eight-day workshop, of which there are 11. “We were so angry at each other, both genders,” Lauren Salzman, Nancy’s daughter, a clever 40-year-old and perhaps the group’s most persuasive junior leader, told me. “Women feel oppressed, and we have so many examples of how that’s true. And the men would try to stick up for themselves and we would all attack them. ... We cut them off constantly just because we’re excited and impulsive. But we didn’t understand that they really felt unheard or disrespected or uncared for. Or withholding sex,” she continued, “we make them work for it and they just don’t understand and they feel fearful and unaccepted.” In Jness, like many of Nxivm’s courses, once the unspoken had been spoken, a new theory, developed by Raniere, took root. Raniere told followers that they must accept that women and men are wired differently. Men are repressed and do not enjoy the same rich experience of existence as women, but they have an understanding of right and wrong; women can be disloyal, have tantrums and get away with whatever they prefer, or as Salzman puts it, “the crazier I get, the more I get.” Raniere also introduced a theory about ancient men that he called “the primitive hypothesis,” emphasizing that men are naturally promiscuous, and women are naturally monogamous. In the larger Nxivm community, most thought Raniere was celibate. But the inner circle knew that he maintained multiple relationships from his home. Consenting adults can surely engage in whatever sexual relationship they prefer, including many women having segmented and siloed relationships with one man. But though Raniere told me that he policed his relationships for ethical shortcomings, the manipulation of his girlfriends, and his girlfriends’ manipulation of other girlfriends, may also have been a feature of his private life. Barbara Bouchey, Raniere’s girlfriend of nine years who left Nxivm in 2009 and was a party to 14 lawsuits involving the group and its related entities, said Raniere kept his other relationships with women, some of whom she calls his “spiritual wives,” secret from her at first. When he didn’t see Bouchey for a few days and she wondered where he had gone, first Raniere and then high-ranked women in the group pointed to her abandonment issues as the daughter of an alcoholic father. Her issues were the problem, not Raniere. Perhaps he was absent because he was trying to teach her a great lesson about one’s expectations of another being.

The two views of Raniere — the world’s most ethical man running an extraordinary self-help organization; a con man who empowered women but retained ultimate power for himself — came up often in my conversation with Bouchey. She said she is not sure if Raniere is a version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, but he might be. But she knew him as a loving boyfriend, affectionate and as measured as when I saw him. He almost never raised his voice, showed anger or talked condescendingly in her presence. “I’ve seen Keith tirelessly mentoring someone over a phobia or becoming a better speaker or giving someone piano lessons, because he has those values,” she said. Later in our conversation, she told me she’s haunted by one question. “Did he really love me?” she said. “I honestly felt it at times. It seemed genuine, especially in the early years.” Raniere was a master of disorientation, of making people believe that up was down and down was up. The way he did this, it seemed, was by promoting both positive and negative endeavors at the same time. This was most evident in the group’s next series of experiments. For men, Nxivm offered a club named the Society of Protectors. Eduardo Asunsolo, a member, told me that each huddle of men would become others’ support system, and if, say, you had a new house you needed to paint, they would show up with roller brushes in hand. To his philosophical theories, Raniere had introduced his followers to a concept called “collateral,” or “collateralizing your word,” which members understood to be “adding extra leverage to your conscience.” If a man didn’t “uphold” his word about running, perhaps the whole group would forgo the next morning’s coffee. “If I know my buddies can’t have their coffee in the morning, I’m going to run,” Asunsolo explained. Collateral took a different form when applied to women. About three years ago, some female members began approaching others on the sly, asking if they felt stuck in their personal growth and wanted to join a secret international women-only self-help group to move quicker in their personal growth. An opening line might be: “I want to talk to you about something that will change your life.” But there was one odd aspect to this overture: This particular self-help scheme did not cost anything. In Raniere’s Randian utopia, true value exchange was always upheld. Everyone paid for courses, or worked fees off through administrative tasks or perhaps nannying for richer members. Some went into debt. In order to learn more about this secret society, to even get the pitch, invitees had to turn over something valuable. And what was truly valuable in life? These were mostly affluent women, so it couldn’t be a diamond necklace; they could always get another. It needed to be something that, if lost, would punish you or damage you — a nude photo, a video confessional about a law you’d broken, maybe even the deed to your house, signed over. This was true collateral, the most direct way to show your trust. And only through complete trust could you truly love another person. You might also call it blackmail. Michele, a 31-year-old member, told me about her experience of joining this group, which some women called the Vow, and others referred to by the solemn name Dominus Obsequious Sororium, broken Latin for “lord over the obedient female companions,” or DOS for short. (Raniere described it to me as a “sorority.”) One day in Albany, Michele recalled that a member asked her to lunch. “This was someone I really admired from afar. I was superexcited and flattered that she wanted to talk to me.” She told me, “I knew if she was involved, there were probably other badass women involved, and I want to be a badass woman — I’m struggling to do that.” Michele said she found her experience of giving collateral “growthful.” To this day, dedicated DOS members insist that they began the secret group themselves when one of them was deeply upset and others decided to help her by pledging ultimate commitment. Over time, the group morphed into a military-style boot camp that was simply trying to address the place of women in the world, to make them realize that they were not victims. When I visited Mack in her gorgeous apartment in Brooklyn — paintings by an ex-boyfriend resting against a wall, Palo Santo just burned in an incense dish — she told me this, too. With a bright smile, Mack, who came to Nxivm when she was unhappy with her TV acting career (she asked Raniere to “make her a great actress again”), explained the way DOS worked. She gestured to a beige love seat and asked if I wanted to sit down, near the tape recorders. The woman who invited you to the group was your master, Mack said, tucking her blue-socked feet under her, or the “representation of your conscience, your higher self, your most ideal.” Masters would help slaves count calories to save them from the trap of emotional eating, according to other women in the group. Masters would dictate an act of “self-denial,” like cold showers or rousing yourself from bed at 4 a.m. and standing stock still for a time. Slaves were told to do “acts of care” for masters, perhaps bringing them coffee. Slaves might be told to abstain from orgasms, ostensibly to heal their negative sexual patterns. Mack said that this was “about devotion” and “like any spiritual practice or religion.” I thought about free will — did she believe in that? She said, “You’re dedicating your life one way or another.” Mack recruited other women and even tweeted at famous women like Emma Watson, inviting them to learn more about her techniques of female empowerment. Many women told me they improved from this scheme, and Mack agreed. “I found my spine, and I just kept solidifying my spine every time I would do something hard,” Mack said passionately. DOS was “about women coming together and pledging to one another a full-time commitment to become our most powerful and embodied selves by pushing on our greatest fears, by exposing our greatest vulnerabilities, by knowing that we would stand with each other no matter what, by holding our word, by overcoming pain.” When the cauterized brand was introduced, it was a scary experience, like any real rite of passage, but some of them kidded around through it. Even if they cried when they were getting the brand; even if they wore surgical masks to help them with breathing in the smell of burning flesh; even if the brand was much larger than they were told it would be and looked like an ancient hieroglyph; even if they were in a state of sheer terror, they were still able to transcend the fear and cry out to one another: “Badass warrior bitches! Let’s get strong together.” In yet another pyramid of the scheme, each master was supposed to bring in slaves, and then, to become masters, those slaves would recruit slaves of their own; an estimated 150 women ultimately joined. Some slaves called each other “sisters.” Mack told me each circle was “like a little family.” Though a majority of women in DOS never had anything to do with Raniere sexually (to me, he was only willing to admit to two) and thus it is impossible to say that DOS itself was a “sex-slave cult” rather than a sex-slave cult and a women’s empowerment scheme, most of the women had been indoctrinated into Jness’s ideas and thus believed that men were inclined toward polyamory and women not, and that in Clifton Park, the natural order of the genders was being taught. Promising to seduce Raniere — which was apparently the way he preferred to be approached sexually, rather than putting himself on the line — was also one of the ways some women later said they were told to show commitment to the sisterhood. It was a test of faith in DOS, a proof of ultimate commitment, of loyalty. And if you didn’t have faith, DOS wouldn’t work for you, and you would lose all your sisters and your chance at badassness. In her apartment, I was surprised to hear Mack take full responsibility for coming up with the DOS cauterized brand. She told me, “I was like: ‘Y’all, a tattoo? People get drunk and tattooed on their ankle ‘BFF,’ or a tramp stamp. I have two tattoos and they mean nothing.’?” She wanted to do something more meaningful, something that took guts. To be honest, I was surprised that she was sitting there at all. And Mack told me that she’d been experiencing some anxiety talking to a reporter. It felt “scary and pressureful,” she said. But Lauren Salzman, who along with Raniere and Clare Bronfman had guided my highly controlled tour of their world, helped her by telling Mack to cast her mind back to when she was a child and received praise at the same time that other kids didn’t. This made Mack feel uncomfortable. But now she was surmounting her fear. “So when I was 8, I created a conclusion and built a foundation of my assumptions that was faulty,” she told me. “Now that I’m 35, I can look back at that 8-year-old’s belief. And I can say, ‘Oh, that doesn’t make any sense anymore.’?” She continued, “Boom, my belief system is upgraded.” Belief is a tricky thing, particularly when it involves taking responsibility for the idea of branding women and being encouraged to talk to a journalist when it may not be in your self-interest to do so. All the more when you include a guru who is an “evolved” being, Explorations of Meaning, “integrations,” joy, hierarchy, money, the stripe path, extreme dieting, secret polyamory and outward-facing benevolent ventures. By the point that many women signed up for DOS, they had taken many steps where they felt they had given consent. While the concept of collateral might have been growthful for Michele, others describe it as a horrifying experience, particularly when they were told to submit additional pieces of collateral sharing the deepest secrets of their parents or those close to them. They felt there was no way out, that their real family wouldn’t accept them after this betrayal. Even today, the overall shame of being identified not only as a member of a cult but as a “sex slave” — of having their control and choice, and, essentially, humanity, stripped from them — has kept many silent. After I interviewed him in Mexico, Raniere stopped using a phone and used an untraceable email account. He relocated to a villa in Puerto Vallarta, which is where he was found by the Mexican authorities this spring in the company of Mack and other women. As he was driven away from the villa in a police car, according to prosecutors, the women gave chase. They were not ready to give up their guru yet. If they let him leave, perhaps they would be exhibiting weakness or hitting against an emotional problem that needed attention. Friday, April 13, was the date set for Raniere’s arraignment in a New York federal court. Within a week, Mack was arrested on the same charges as Raniere. The F.B.I. accused Raniere of “a disgusting abuse of power in his efforts to denigrate and manipulate women he considered his sex slaves ... within this unorthodox pyramid scheme.” The criminal complaint claimed that the severe DOS diet was not for the women’s good, but to please Raniere, who, it asserted, sexually prefers very thin women, whom he entertained in a Clifton Park bachelor pad called “the Library,” outfitted with a bed and a hot tub. Prosecutors also claimed that Raniere, in the 1980s and early 1990s, had repeated sexual encounters with under-age girls. (He denied this to me.) Mack was Raniere’s personal slave, according to the F.B.I. The collateral she gave him as her “master” was chilling: a contract declaring that if she broke her commitment, her home would be transferred into his name and future children birthed by her would be his, as well as a letter addressed to social services claiming abuse of her nephews. And when slaves took nude photos and gave them to masters as “collateral,” believing only women were involved in the group, Mack sent some collateral to Raniere. In one case, upon receiving digital photos, Raniere sent her a text reading “all mine?” with a smiling devil emoji. Perhaps in order to please him, Mack decided to take on appealing young women as her slaves; she told me knew she needed to “get right” with her longstanding jealousy issues with younger, more attractive women. Allegations include that late at night, she set up a slave on a walk with Raniere. He blindfolded the slave, led her to what seemed like a shack and tied her to a table, after which another person, whom she hadn’t met before, performed oral sex on her. Mack pleaded not guilty to the charges against her, but eventually people noticed that the symbol branded on the women not only included a “KR” but also seemed to have an “AM.” She may have been, then, both victim and victimizer. In Mexico, Raniere insisted to me that claiming he brainwashed anyone was ridiculous. Brainwashing was a farce, a scientific impossibility, and indoctrination can be positive. “What is wrongful about my indoctrination?” he asked, rhetorically. But some ex-members disagree. Raniere’s ex-girlfriends from the 1990s and 2000s with whom I spoke said that while they were not expressly part of a master-slave ring, they felt entrapped by this exceedingly strange man, who was a whirling dervish of ideas, but also sort of lazy, spending his days monologuing to devotees, playing volleyball, bedding women and making women do his bidding with other women. “He’s got everything exactly the way he wants it,” one ex-member declared in court documents. “He’s not trying to succeed; he’s trying to enslave.” What they learned from Nxivm was that humans are highly programmable. Free will is a limited quantity at best. It has to be earned by intensely building self-awareness, as well as an awareness of others, and their potential for manipulating you. Raniere did not express remorse about his claimed role in DOS nor even admit to it to me. He was a wandering prophet, not a mastermind; he talked to me about angry former lovers, ex-members’ “loose lips” and extortion letters that had come his way. When addressing allegations by ex-members of abusing his power, Raniere gave me an answer steeped in Randian principles of value exchange. “I think in many of those circumstances, I’m investing,” he told me, pursing his lips a little. “And when they accuse me of taking from them, I say, ‘You know, honestly, I’m investing, so if anything, maybe I don’t get a return on my investment, but I made that choice.’?” Before he was arrested, Raniere reminded the remaining flock that reports about Nxivm in the media could not be trusted. The media was dishonorable. And the Nxians weren’t wrong that reporters were gunning for them: While I was in Albany, a photographer in a black pickup truck drove hastily by a group of women with whom I was standing, and we could see him snapping pictures inside the cab; it felt threatening and invasive, and I could see how Bronfman and others could be worried that they could be hurt. Raniere also stressed that departing members were under the sway of the scientific principle of cognitive dissonance. They had decided he was bad, thereby they had to make him very bad, to make their defection feel good; they would probably claim that the 18-year-old with Crohn’s disease I met in Salzman’s kitchen was just there for Raniere to bed her. To bolster the point that Raniere was the ethical one, he noted that DOS has not publicly released any woman’s “collateral” (this isn’t an impressive point, given how legally problematic that would be). But he also told me that Nxivm hasn’t publicly released information about defectors’ private lives, traumas and family issues, knowledge they clearly possess. He insisted that he wouldn’t give up that trust. At an early May hearing for both Raniere and Mack at United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York, in Brooklyn, Raniere’s lawyer, Marc Agnifilo, whose firm represented Dominique Strauss-Kahn and is currently employed by Harvey Weinstein, told a crowd of reporters that Raniere was unwilling to plea bargain. “Everything was utterly consensual — it was adults making decisions on their own of their own free will, and that’s what the trial is going to show,” Agnifilo said. “A lot of adult, strong-minded, free-willed women made decisions for their own lives.” Federal sex-trafficking laws meant to protect women and girls impacted by poverty and exploited may apply to the odd nexus of possible coercive sex and forms of commerce in DOS. Each charge of sex trafficking carries a 15-year minimum sentence. New criminal charges may also include racketeering, on the theory that the DOS organization in general was devoted to criminality, as well as financial charges related to supposed crimes previously outlined by an apostate girlfriend, such as bringing cash from Nxivm classes taught in Mexico over the border and visa violations. In the hushed, carpeted courtroom, a judge sat on the terribly tall bench as three female prosecutors in sharp stiletto heels faced Raniere, and Moira Kim Penza, the lead prosecutor, wove an argument about her case. Raniere and Mack did not look at each other once. Raniere wore a gray jumpsuit, wrinkled in the back from perhaps lying down in his cell; when he entered, his eyes darted to and fro. Mack’s hair had lost its blond highlights, and she was painfully skinny. She held herself completely still except for a tiny shake. 205 Comments The Times needs your voice. We welcome your on-topic commentary, criticism and expertise. Correction: May 31, 2018 An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of a Mexican newspaper company. It is Grupo Reforma, not Groupo Reforma. Vanessa Grigoriadis is a contributing writer for the magazine. Her book about consent and sexual assault on campus, “Blurred Lines,” was published last year.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.