Clergy Sex Abuse Report Could Be Delayed Months; Here's Why the Legal Process Is Complex

By Ivey DeJesus

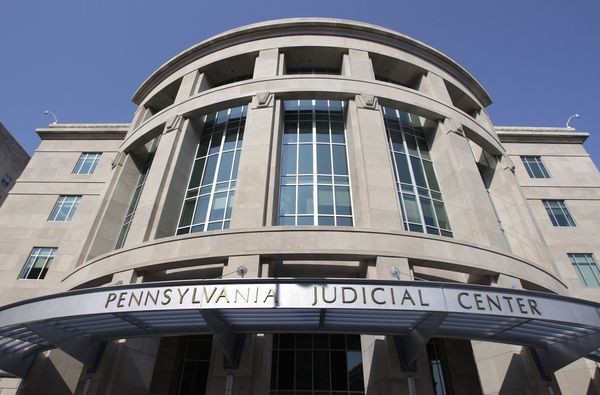

This report has been updated to clarify information on the unidentified and unindicted individuals. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court was clear and succinct on Wednesday when it barred the release of a long-awaited statewide grand jury report into clergy sex abuse. The court's four-sentence order offered no explanation as to why the court made the decision; what, if any, vote count was taken; nor did it give indication as to whether the order signals that the court will hear future arguments on the matter. The seemingly abridged order simply blocked the Office of the Attorney General and the Cambria County Court of Common Pleas judge overseeing the grand jury from releasing the findings of the probe. The order may have been blunt, but it was within the strictest bounds of the law. "The mantra here is that grand juries are secret and that's the problem," said Nicholas Ressetar, chief law clerk with the Harrisburg-based law firm Costopoulos, Foster & Fields. "Their dilemma is, 'How could we become more transparent without giving up the names of the individuals or institutions making these claims?' It's a dilemma really." The grand jury report will be released to the public at some point but it could take months, Ressetar said. Other than the briefly stated order, all documents and procedures pertaining to the grand jury investigation remain under seal and that includes explanations of any kind. "All grand jury matters are sealed including the rationale," said court spokeswoman Kimberly Bathgate. Wednesday's order comes a few weeks after Cambria County Court of Common Pleas Judge Norman A. Krumenacker III denied a request from individuals named but not indicted in the grand jury findings an opportunity to defend themselves against accusations made in the report. The report is the outcome of an 18-month-long grand jury investigation into allegations of child sex abuse across six Roman Catholic dioceses in Pennsylvania: Harrisburg, Pittsburgh, Allentown, Erie, Scranton and Greensburg. Earlier this month, all six respective bishops, the heads of the dioceses, received a copy of the 884-page report, which ostensibly lays out findings widely expected to expose predatory priests and possible mishandling or cover-up of sexual abuse by church officials. Krumenacker denied the motion of these unidentified individuals, citing overriding public interest in preventing child sexual abuse and exposing predators. However, he granted them the opportunity to appeal. Wednesday's order stunned victims and advocates, and arguably engendered an onslaught of questions about the process and the rationale taken by the court. Arguably, it did not stun Attorney General Josh Shapiro. Back in May 21, Shapiro in a statement to the press regarding release of the findings said: "I expect to speak publicly on this comprehensive investigation by the end of June. The only thing that could stop these findings from becoming public at that time is if one of the bishops or dioceses would seek to delay or prevent this public accounting." Shapiro's office on Wednesday vowed to continue to fight for victims and the release of the report. Clarity is not easy to come by on this issue, particularly because this legal process has little precedence in Pennsylvania. But there is an even more convoluted reason: The individuals who filed the motion to the Supreme Court are presumably the same ones who petitioned Krumenacker's court seeking to defend themselves. They are named in the report, but not indicted. These individuals may have been witnesses to crimes or have known about crimes but did nothing to report them. Still, it would stand to reason to presume that these individuals are named in the connection of a commission of a crime but not charged because the statute of limitations for their alleged crimes have expired. Since they are not charged with a crime, they, therefore, have no legal pathway to defend themselves against accusations. "This is a problem in Pennsylvania," Ressetar said. "If you are charged with a crime, you can establish innocence by going to trial, but in these cases, because the statutes have passed, these people being mentioned for acts that occurred 30, 40 years ago, have no way to vindicate themselves. They can't go to trial. There's no one they can sue. They are just left hanging out there with no way to prove their innocence." To date, one priest has been arrested as a result of the grand jury investigation. Krumenacker may have denied their motions but he saw enough merit in their arguments to certify them for appeal. In Pennsylvania, only the state Supreme Court can hear an appeal on a grand jury investigation. "That's a big deal," Ressetar said. "He granted these movants a procedural victory that allows them to appeal to the Supreme Court. Krumenacker paved the way for them to do what they've done." In some states, individuals who are not charged with a crime cannot be named in an investigation in connection to allegations of having committed a crime. Pennsylvania is not one of them. poster.jpg This poster was produced by the Office of Attorney General in conjunction to the 2016 37th Statewide Investigative Grand Jury report that found more than 50 priests in the Altoona-Johnstown diocese over the past 40 years had sexually abused children. The poster shows a timeline of names of predators. Mark Pynes | mpynes@pennlive.com Mitchell Garabedian, an attorney who has represented hundreds of victims in suits against the Catholic Church, argues that what is playing out is standard operating procedure by the church, which has been embroiled in a scathing worldwide clergy sex abuse scandal for decades. Garabedian theorizes that the high court is considering the rights of the church laid out in the First Amendment, which prevents the government from making any law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise of religion. "The church is probably taking the position that its constitutional rights have been or may be violated with the release of the documents if they expose church's beliefs or conduct that are not wrongful," Garabedian said. "The constitution protects religious beliefs and rights and conduct which is not wrongful, of course the constitution does not protect the wrongful conduct of church members. If the document indicates wrongful conduct...those documents should be released and that is the issue the court is probably addressing at this point." All six bishops at the helm of the dioceses that were investigated have declared support for the grand jury report and its release. The church's legislative branch, the Pennsylvania Catholic Conference, noted that each diocese has had autonomy in dealing with the investigation. Conference spokeswoman Amy Hill in April said: "The Catholic Church has embraced the need to make this right for survivors. Pennsylvania's dioceses have fully cooperated with the grand jury's investigation." Garabedian, who was featured prominently in the film "Spotlight" - which chronicled the landmark investigation into clergy sex abuse by The Boston Globe - isn't buying what church officials say. He said he has seen this exact scenario play out time and again. "It's a constant battle," he said. "It's a constant issue in cases with the Catholic Church. The First Amendment and statute of limitations are always at the forefront." In the Boston scandal, the archdiocese argued its First Amendment rights in attempting to shield church documents. The Boston Globe took the church to court and won. The archdiocese was forced to release its documents. The newspaper published its groundbreaking report in 2002, showing decades old systemic child sex abuse by priests and the cover-up by the church.

Garabedian said the same pattern is likely playing out in Pennsylvania. "These individuals are trying to use the shield of the First Amendment to protect the release of the documents and also saying that the statute of limitations have expired so their cases should have been dismissed in the first place." Where all this goes from here is anybody's guess. The Supreme Court may decide the issue on the current standings or it may schedule additional briefings or hear arguments. The one startling possibility is the potential time frame for a process that is already nearing a two-year mark. "We could be talking six months to a year. It's all speculation really," Ressetar said. The fact that we are about to enter into the slow days of summer vacations does not bode well for any swift movement. Ressetar, however, is confident that the report will be released - that this latest order in no way signals a permanent block to the report. "This report is going to come out," he said. "It's just a question of when and in what format. A couple of people are going to be taken out. This isn't some kind of conspiracy by the Roman Catholic Church to keep it concealed. They can't block it. It doesn't work that way." Garabedian implored church officials to clear a path for the report. "We see this constantly in these cases," he said. "The church says the right thing but does the right opposite. It's a heartless approach. The sexual abuse of children is just heartless. The church should tell truth, be transparent and allow victims to heal."

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.