|

Women say ex-Fort Worth youth pastor abused them as teens. 37 years later, he finally resigns

By Sarah Smith

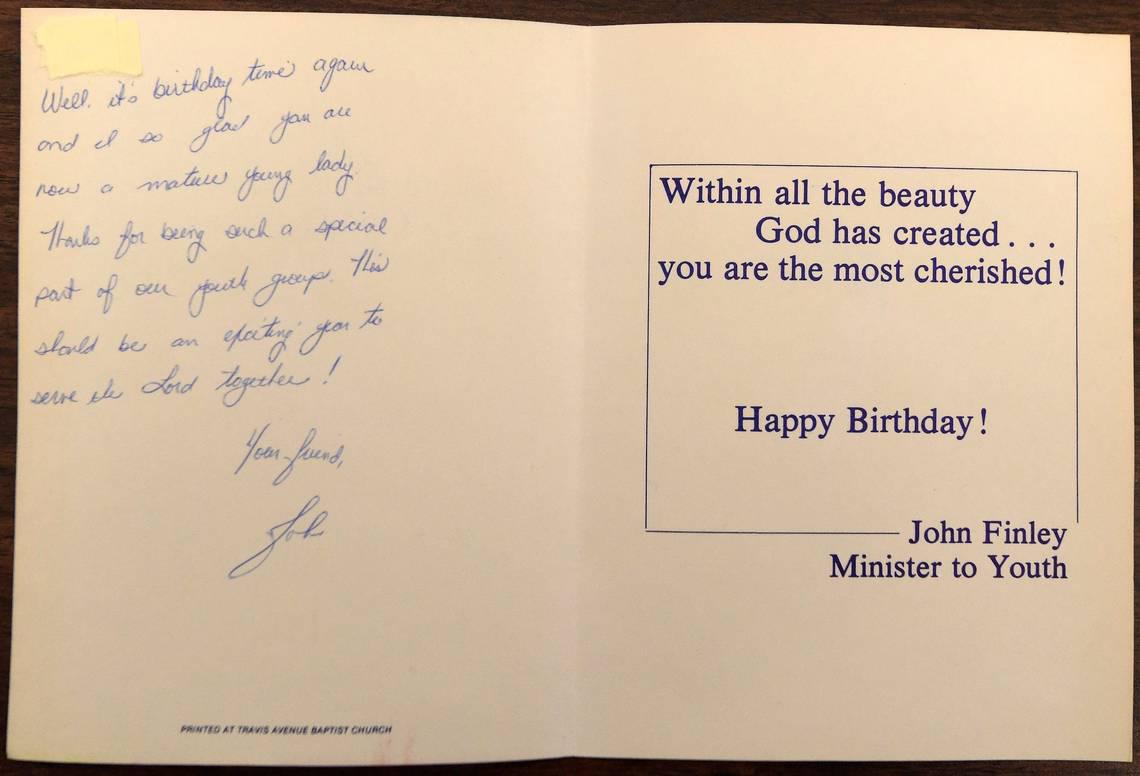

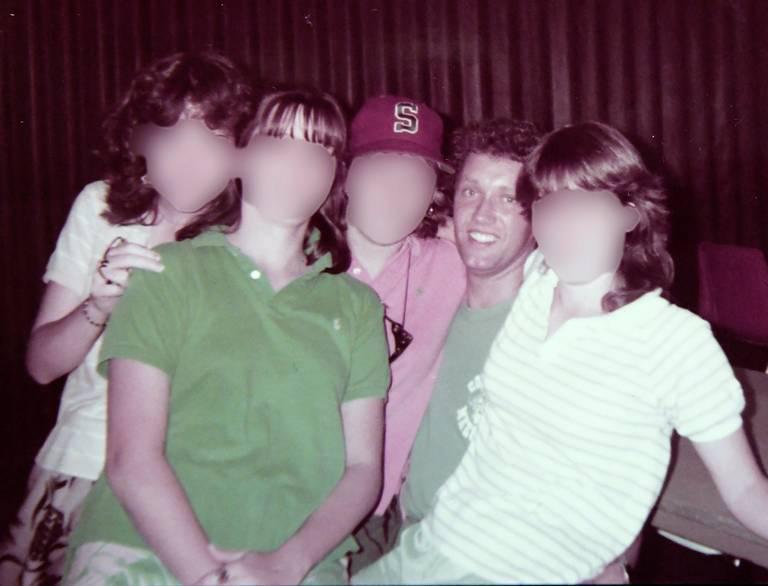

[with video] On April 8, Pastor John Finley stood before his congregation in Tennessee with an announcement. After 31 years at the church, he resigned. He held a microphone and read from a piece of paper. “I made some poor choices and was involved with two females in inappropriate behavior,” Finley said. “There was no sex. Both ladies were over 18. In the best interest of our church, I choose to resign immediately.” But the women who sent a letter that spurred Finley’s resignation from Bartlett Hills Baptist Church near Memphis have a different story to tell. They were ages 15 and 17, they said, when the alleged abuse began at a Southern Baptist church in Fort Worth. It was true he hadn’t had sex with them, but he’d done more than kiss them, they said. He touched one’s breasts and put the other’s hand on his naked erection, they said. The alleged abuse began 37 years ago at Travis Avenue Baptist Church, where Finley served as the youth minister for five years. Travis Avenue is well known in the Southern Baptist community, with strong ties to Fort Worth’s Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. One of the women said she never told anyone about the abuse until college. The other tried once, telling a youth worker at the church. A rumor even reached a deacon. Still, Finley stayed at the church. The Travis Avenue of today is pastored by Mike Dean, who arrived in 1991, five years after Finley left. He has worked with both women to confront Finley’s church in Tennessee and now wants his own church to acknowledge what happened, while also trying to make Travis Avenue a place of healing. “That angered me, that we missed that opportunity to set this straight 30 years ago,” Dean said. “I was just angry that it happened and we couldn't stop it or didn't stop it.” The story of Travis Avenue unfolds against a backdrop of the Southern Baptist Convention’s own recent reckoning with how it deals with abuse. In May 2018, Paige Patterson, head of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, was fired over mishandling reported sexual abuse. At June’s annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention, which took place in Dallas, much of the conversation revolved around the treatment of women and how churches ought to deal with reports of abuse. It took 15 years’ worth of attempts to reach out to Bartlett Hills to get Finley to resign, according to the women and their advocates. Bartlett Hills leaders maintain that the two women were adults when the incidents took place. Finley's wife, Donna, told the Star-Telegram there had been no more than kissing and that both women were adults. She said her husband would not comment and provided the name of his lawyer, who did not respond to repeated requests for comment. “It’s been life-altering for me,” said Maria, one of the women who said she was molested by Finley. She’s 51 now and has asked to be identified by a pseudonym. “I believe that God has blessed me with a full life and a family and love and friends, but I don't necessarily think this is the life, originally, that I was meant to have lived." The youth pastorJohn Finley, now 62, became Travis Avenue’s youth minister in 1981, according to the church’s history book. In his mid-20s, he favored bright shirts with bright ties. The kids called him “John.” His favorites loved him and remembered him as quick with a joke and easygoing, just like a youth minister should be; the boys not in his inner circle bragged about dumping a toilet in his yard. Sarah Beth — a pseudonym — said she was 15 when her abuse began in 1981. She’s 53 now and up to that point had attended Travis Avenue her whole life. The first incident occurred on a youth trip bus, she said, when she thinks Finley thought she was asleep. She said he sat next to her and touched her breasts. She froze and waited for it to end. The alleged abuse went on from when Sarah Beth was 15 until she was 18, from 1981 to 1983, she said. She remembers one time when Finley rubbed her leg on a youth group trip to a Fort Worth buffet and arcade while she played a video game. Another time, she said, he pinned her against his truck door, kissing and touching her. Still another time, she remembers him touching her breasts. Sarah Beth blocked out some of the alleged abuse. “One time — and I’m not sure what age this is — I remember I was kind of watching it happen. It’s like I wasn’t even there. I was kind of 'up here,’” she said, gesturing to the ceiling, “and I’m like, ‘Oh, is this happening?’” As an adult, she said, having had normal relationships, she looked back and thought, “How was that enjoyable to him? I didn’t reciprocate.” She went away to college in 1983. She’d never told anyone at the church what happened. When Sarah Beth was at college, Maria, a girl two years her junior, came to Finley’s attention. Like Sarah Beth, Maria was a leader in her grade. She always wanted to do the right thing and considered herself a rule follower. In August 1984, when Maria had just turned 17, the youth choir was on a bus trip to Colorado. Maria said the group was playing cards and trading seats, sitting on one another’s laps and lying down, and she wound up on Finley’s lap. She didn’t realize it was inappropriate — she had barely even kissed a boy then. So she didn’t think about it, she said, until Finley started touching her from behind. “You know how when you're nervous and you can feel your pulse just beating?” she said. “I remember that feeling, and I'm sure my face was red, my ears were red. I just couldn't believe it was happening. Then he started just kinda raising his knee up underneath me, and I knew then that something was very weird and wrong.” Little incidents happened throughout the trip, she said: pointed looks, Finley rubbing his arm or leg against hers. To this day, she remembers his blue eyes and the puffy bags under them, staring at her. When the bus pulled up to drop the youth group back at church, Finley helped unload suitcases. Maria went to get hers when Finley, she said, grabbed her arm. “He looked at me with his big blue eyes and he’s like, ‘Hey, hey, I love you. You know I love you, right?’” she said. She felt furious. She hadn’t processed what had happened and she felt sure Finley was trying to cover himself. Mark Leitch was a member of the youth group at the same time as Maria, an active member but not a favorite of Finley’s. On the bus home from that Colorado choir trip, he said, he saw Finley touch Maria’s bottom with an erection. Leitch told his parents, who didn’t believe him. His girlfriend, he said, told her parents — and her father believed her enough to speak to others. One of the others was a deacon and the father of another 17-year-old in the youth group, who was one of Maria’s best friends. Amanda — who, on advice of her attorney, has asked to remain anonymous — remembers her parents called her into the kitchen and told her to ask Maria if Finley was doing anything inappropriate with her. Amanda and Maria went to McDonald’s. Over soda and fries, Amanda tried to get Maria to tell her if anything was happening. Maria denied anything was going on. Amanda took the denial back to her parents. Nothing more was done. By the time the church’s ice cream social rolled around a few weeks later, Maria felt like she had to tell somebody what was happening. She asked one of the youth volunteers — a younger adult — if they could talk. They sat down on the steps on the side of the church, and Maria talked in circles, not making eye contact. She rocked back and forth. Finally she told the youth worker what happened on the choir trip. Looking back, Maria thinks the youth volunteer didn’t know what to do. The woman’s first reaction, Maria said, was to ask if the man touching her was her husband. No, Maria said, and she told her who it was. The volunteer asked a few details, if it had happened since the trip. “Thank you for telling me,” Maria remembers her saying. “I’ll check on this.” The youth volunteer wrote a statement in January 2018 about what had happened. She said she had heard about rumors of Finley and Sarah Beth before Maria approached her. She said she approached Finley in his office in 1984 with the rumor about Sarah Beth and Maria’s accusation. “He admitted to the relationship with [Sarah Beth] but that it was over,” she wrote. “As far as [Maria] was concerned, he told me it only involved a kiss, and that he would leave her alone.” The statement was provided to the Star-Telegram on the condition that the woman who wrote it not be identified. Finley, she wrote, said he would talk to the then-pastor of Travis Avenue, who is now dead. The youth volunteer didn’t know if he ever did. She declined to comment further. The youth worker told Maria she’d spoken to Finley and that he promised the behavior would end. But the incidents, Maria said, continued, and by then, Finley had warned her not to tell or he’d get in trouble. At that point, she decided it was useless to press it further. Maria said the abuse happened once or twice a week. Finley, Maria said, made a point of driving her home after youth events. He would grab her and kiss her and touch her in his car. With a few exceptions — once, putting her hand on his penis — she said, he usually touched her. Sometimes, she said, he would express guilt. He’d kiss her and touch her in a parked car and then move back to the driver’s side, repeating, “I don’t know why I keep doing this. I’m a good person, I love God. I’m a good man. I just don’t do this.” Maria said she thought, “How come people don’t see this? How come people don’t know this? Surely people see this.” John Finley left Travis Avenue Baptist Church in 1986. When Maria found out, she was working in a Fort Worth department store with a couple of other friends from church. When a friend told her, she ran to the back room and sobbed. A 1989 directory from the Tennessee church John Finley would resign from almost 30 years later shows him smiling from a page of staff members in a red tie and a gray suit. He has the same tight curly hair the Travis Avenue kids remember. He’s listed as the church’s minister of education and youth. 'I knew this day would come'Away at college, Sarah Beth began telling some friends — several of whom have spoken to the Star-Telegram and confirmed her accounts — what had happened. In the early 1990s, she told her parents. Watching the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings — and Anita Hill being questioned as she testified about being sexually harassed by the soon-to-be Supreme Court justice — rattled her enough that her mother knew something was wrong. “It felt like, ‘This lady’s saying stuff, and people aren’t believing her,’” she said. “And that’s on the national stage. What’s going to happen to me if I tell anyone?” In 1994, Maria and Amanda drove to visit a friend’s new house in Fort Worth. Brad Ward had been a member of the youth group and had been told what happened to Sarah Beth. Ward asked if Maria and Amanda had heard about Sarah Beth and told them that she had been abused by Finley. Maria started crying when she and Amanda got back in the car. She told Amanda that Finley had molested her, too. Through some friends, she got Sarah Beth’s number, and the women talked about their experiences. After she heard about Maria, Sarah Beth called Finley. She confronted him about what had happened. She remembers him saying: “I wish you girls would leave me alone.” Maria also called Finley. She asked, “Why did it happen?” She described his response as flippant. “It’s just one of those things, and I’m sorry,” he told her. In the late 1990s, Sarah Beth wrote two letters to Finley’s church in Tennessee, one to the head of the deacon board and one to the personnel chairman. She can’t remember their names now, but she detailed the allegations against Finley and had a phone conversation with one of the men. From Sarah Beth’s point of view, she’d done what she could. They’d been warned. The church would be warned again. Scott Floyd is the minister of counseling for Travis Avenue and serves as the director of the master of arts in counseling program at B.H. Carroll Theological Institute in Irving, Texas. Sarah Beth went to him for counseling in 2003 about what had happened to her, and he learned there was another woman who had been abused as well. He heard Maria’s story separately and said he realized there were similarities between the two. “It disturbed me a lot, and I struggled with it,” Floyd said. “I felt like I needed to do more than just try to help them individually.” He got the women’s permission to do research. He spoke to Mike Dean, the Travis Avenue pastor, who agreed to let Floyd do anything the women were comfortable with. Floyd spoke to others who had been members of the youth group at the time. And then, with the women’s permission, he reached out to two officials at the church with a letter laying out his findings — and to Finley himself with a letter and phone call. “The first thing he said to me is, ‘I knew this day would come,’” Floyd said. Floyd provided details about the allegations against Finley on the phone. Finley, he said, denied nothing. Finley said there was no intercourse, there had been only two girls and that he was repentant. He also said he had not worked with children since being at Travis Avenue (according to the old church directory and Finley’s resignation statement, this is untrue: He worked as a youth minister at the Tennessee church before becoming the pastor). At Floyd’s urging, Finley agreed to get counseling and allow Floyd to check in with the counselor, Floyd says. Floyd said Finley went to several sessions. “What I was hoping to do is make other people aware of what he had done in the past,” Floyd said. “I was trying to contain the likelihood he could do anything else.” Finley would stay at the church until 2018. 'What more can our church do?'On April 3, 2018, just after he resigned from his position as the student minister of Tennessee’s Bartlett Hills Baptist Church, Nick Daniel received a package that had been FedEx-ed overnight to his home address. When he opened it, he found a letter detailing five years’ worth of alleged sexual abuse by John Finley at the Travis Avenue church in Fort Worth during the 1980s. Finley had hired Daniel at Bartlett Hills. “This day will serve as a line of demarcation for those receiving this document,” read the letter, written by Amanda and Sarah Beth and approved by Maria, dated April 2, 2018. “It will mark the day each of you became aware that your Executive Pastor committed sexually criminal acts and now have a responsibility to act in order to protect your church and its congregants.” Daniel was shocked. John Finley had been at Bartlett Hills for 30 years. But the accusations in the document were detailed — and there were enough to make him doubt Finley, Daniel said. Five other Bartlett Hills officials received identical letters the same day. The next Daniel heard, Finley had resigned — with a statement different from what the documents said had happened. “For me personally, it becomes a struggle," Daniel said. He is now working at another Tennessee church. “I worked with this man for eight years, I never knew any of this. It makes you question your own ability, your own discernment.” Spurred by the #MeToo movement and its spillover into the church world, Sarah Beth and Maria had decided they were ready to try again. This time, Amanda — their old friend from youth group — took on a role as their advocate. In January 2018, both women said, they filed reports with the Fort Worth Police Department. The report filed by Sarah Beth alleges that Finley sexually assaulted her several times from the time she was about 15 to the time she was about 17 years old. The report says Sarah Beth told police Finley kissed her on multiple occasions. Once, while fully clothed, he lay on top of her on the floor, kissed her and became aroused, the report said. On another occasion, Finley put his hand under her shirt and rubbed her breast, Sarah Beth told police. Maria provided the Star-Telegram with a portion of the report she said she filed with police. It does not identify Finley but says Maria reported that she was assaulted by her youth minister on and off for two years, beginning around 1984. The report alleges the youth minister touched her buttocks, then pushed his knee into her groin. It also alleges the youth minister kissed her, fondled her breasts and asked her to kiss and touch him. In the letter to Bartlett Hills, Amanda put herself forward as the advocate who would be the point of contact with the church. Ted Rasbach, chairman of the personnel committee at Bartlett Hills, responded to Amanda and declared himself the spokesman for the church. In an interview, he said he and the other recipients immediately took the letter to Finley. Finley, he said, “acknowledged he had committed inappropriate behaviors but that they were not with minors.” Rasbach, who has been at Bartlett Hills since the early 1960s, thought Finley had been a wonderful pastor. He’d never heard any allegations against him of inappropriate behavior until the letter arrived. “The communications in the letters had no basis in facts,” Rasbach said. On April 8, Finley read his resignation speech to the church, saying as much. Backlit by the chancel’s purple lighting, he told the church that he had been involved in “inappropriate behavior” with two women, both over 18, over 30 years ago in another church. “Nothing like this has happened in our church,” he said. As he walked off the chancel, a congregant called out, “John, John, please don’t do this. We’ve all made mistakes.” Rasbach provided a transcript of Finley’s remarks. “I was angry when I saw that,” Maria said. “I was like, 'How can you sit here and lie? You have the opportunity to come clean.' ” Amanda sent an email the day after Finley resigned, demanding that the church correct his resignation speech. Rasbach asked for police reports. Amanda promised to travel to Tennessee with other documents and obtain the police reports. Maria would travel with her, ready to tell her story to the entire congregation. Ultimately, Rasbach replied that the committee decided a visit would be unnecessary. “We’re not sure what the two ladies are wanting, at this point,” he said. “John Finley has resigned. What more can our church do?” Moving forwardDonna Finley, John’s wife, picked up the phone at the couple’s Tennessee home on July 3. More than anything, she wished this whole thing would go away. “I can tell you for certain it was no more than kissing,” she said. Referencing Sarah Beth, who signed her real name to the letter to Bartlett Hills, Donna Finley added, “She should be over this. She cannot live her life trying to destroy my husband.” Donna Finley said her husband would not comment and deferred comment to his lawyer, Jeffrey Jones, an attorney based in Bartlett, Tennessee. Jones did not respond to multiple emails and phone calls over the course of the last week. The Star-Telegram sent Jones a list of 34 questions regarding each accusation Maria and Sarah Beth made against Finley, as well as recollections others had of interactions with Finley over the nearly four decades of his time at the Travis Avenue and Bartlett Hills churches. On Sunday, July 8, Pastor Mike Dean informed his congregation at Travis Avenue Baptist Church in Fort Worth of what had happened. He put out a statement from the church, outlining that the church had learned about the allegations in 2003 and had worked since to help Sarah Beth and Maria warn the Tennessee church. “Our first instinct is self-defense, and yet I knew we needed to resist that,” he said in an interview. “This is something that happened. It happened here at our place.” The church has more safeguards in place than it did in the 1980s: background checks, windows between rooms, a two-adult policy for staff working with children. And the youth minister copies his wife or another worker when texting a student. He hopes that Travis Avenue can help other churches deal with such circumstances in the future and use the situation to minister to abuse victims in its own congregation. In December 2017, before confronting Bartlett Hills, Amanda had sent an email through the Southern Baptist Convention’s website asking how to turn in a pedophile. She never got a response. She wrote an email to the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission — the public policy arm of the Southern Baptist Convention — and presented the situation. She asked for guidance. “Specifically engaging in this matter is not in the scope of our role, authority or ability,” Lauren Konkol, the commission’s team coordinator, wrote in an email back to Amanda on Feb. 3. “Within Southern Baptist churches, the local church is the highest authority, and we as a denominational organization have no authority to remove or rebuke any local pastor.” Konkol deferred response to the commission’s vice president for public policy and general counsel, Travis Wussow. “We’ve been grappling with what is our responsibility, what is our mandate,” he said. “But what autonomous doesn’t mean is we are autonomous from every authority.” Criminal justice, he said, belongs to the state to execute. The autonomy of the local church — a backbone of the Southern Baptist Convention, which is technically a voluntary association of local churches — can be a sticking point in rooting out abuse. The SBC itself is hesitant to publicly rebuke pastors and churches. A proposed database of offenders, which has been talked about since 2007, has been repeatedly defeated. In 2008, the SBC executive committee announced it would not support it, citing the “belief in the autonomy of each local church.” After this year’s convention and its focus on abuse, the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention has been tasked with studying the viability of creating one. No church has yet been kicked out of the SBC for mishandling abuse, but Roger Oldham, spokesman for the SBC’s executive committee, said it could be done. “Who has the authority to go to a church and say: ‘Your pastor has a problem?’ There isn’t an authority within our convention with the legitimacy to do this,” said a lawyer familiar with the SBC, who required anonymity to speak freely. “Southern Baptists as a whole have to look at each other and say: ‘Let’s do something about this.’” After Finley’s resignation, Amanda sent an email to Mitch Martin, executive director of missions for the Mid-South Baptist Association, a Tennessee-based network of Southern Baptist churches, outlining what Finley had allegedly done and the discrepancies in his resignation speech. In an email to Amanda, Martin promised to “discourage John from pursuing vocational ministry” and, if a church came asking about him, he would “tell them that I cannot in good conscience recommend him.” Martin told Randy Davis, president of the Tennessee Baptist Mission Board, that Finley had resigned and that there had been accusations made against him. Davis said he didn’t know the specifics. He hasn’t informed other churches about Finley, he said, because he doesn’t have enough firsthand information. He said he wouldn’t necessarily be opposed to alerting the churches in the Tennessee Baptist Convention’s network to an abuser, though. “It is pressing the envelope of church autonomy, but I believe we need to become more involved in informing our network of churches how they can understand their responsibilities in vetting someone,” he said. “We’re desiring to be very proactive in helping churches to deal with these things openly.” Long-term effectsMaria never dealt with her emotions until she wrote her impact statement to send to Bartlett Hills. For a while, she felt like nobody cared. For years, she carried blame and self-loathing for what happened. Mark Leitch, the boy on the bus who tried to alert his parents to what he saw happening with Maria, is 51 now and still living in Fort Worth. He’s carried the incident with him ever since, as well. “As a young man, I felt like I should have done something to protect my friends,” he said. “I just hurt so bad that I didn’t do anything.” Sarah Beth feels like the alleged abuse — though it was physical — affected her more psychologically and emotionally than physically. As an adult, she asked herself how the abuse kept happening. She was disappointed when she found out recently that a youth worker had been told what happened to Maria and that there had been rumors about her, yet Finley remained at the church. “Why didn’t anyone check into that?” she asked. “I feel like the opportunity has come up to help other people — to either prevent something or help people who have been hurt. I’m trying to do what I wish someone would have done for me.” Contact: ssmith@star-telegram.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.