|

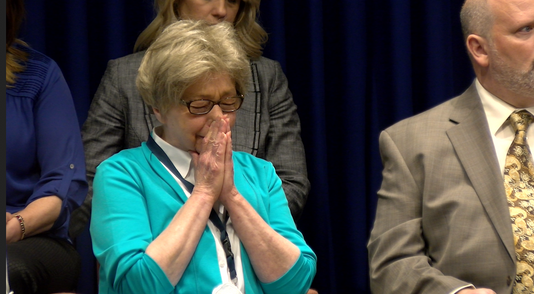

Pa. grand jury: When she reported being abused by a priest, the church investigated her

By Mike Argento

[with video] On Thursday, Juliann Bortz’s daughter stopped by her house and spotted something out of the ordinary. In the driveway of her home in the Allentown suburbs was an aerosol can. It looked like it had been placed there, the white spray can standing upright in the middle of the driveway. Her daughter was alarmed. Bortz didn’t think it was anything, and she offered to check it out. Her daughter warned her not to. It was weird. There was no construction being done in her subdivision, no work crews marking the locations of underground pipes and wires. Her daughter suggested, insisted, in fact, on calling the police. The reason for her caution was that Bortz had been in the news recently. She was among the victims preyed upon by Catholic priests who sat on the stage when state Attorney General Josh Shapiro announced the results of the two-year-long grand jury investigation into child sexual abuse perpetrated by priests in six Pennsylvania dioceses. She has been an outspoken advocate for the victims, having been molested by a priest when she was a girl attending Catholic school in Allentown. She was sure the can was nothing. But she couldn’t be positive. Since the grand jury report was released – identifying more than 300 priests who preyed on more than 1,000 children – some victims who have gone public with their stories have received threats. She messaged some of the members of the survivors’ group she is involved with, and they suggested she contact the attorney general’s office. The AG’s office said she did the right thing calling the cops. It’s better to be safe than sorry, they said. Bortz said, “It was like a see-something-say-something situation.” The cops arrived, and it turned out to be nothing. It could be she was being overly cautious, or even paranoid. But her experience has been that just because you’re paranoid, it doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you. Bortz learned that lesson when she read the grand jury report and found out that the church and its lawyer had investigated her after she had reported the abuse and had come upon information that they could possibly use to discredit her. None of the information did, but until then, she had no idea that the church had dug around in her life – even investigating her daughter – to find something that they could possibly use to silence her. “It’s crazy,” she said. “It’s absolutely crazy.” It was part of the playbook followed by the church to cover up decades of abuse perpetrated by priests in just about every parish in the state – discredit the victim. Shapiro called it part of the “weaponizing” of the Catholic faith that permitted priests to prey upon children for decades with few consequences. Part of the cover-up included trying to discredit victims, to victimize them again by digging through their lives to find disparaging information, information that the church believed would cast doubt on their character and their stories. Bortz was one of many. But her story was highlighted in the grand jury report as one that illustrated how far the church was willing to go to discredit those who reported the trespasses of priests against the innocent. *** The church was the center of her family’s life, Bortz said. She was born in McAdoo, a small town in Schuylkill County where her father toiled in the coal mines. The family moved to the Allentown area when she was a girl and enrolled her in Catholic school. It was not unusual to see priests in her home. Their parish priests were family friends. Her mother cooked for the church. Her father often did odd jobs around the church –gratis, of course. One priest even had a special set of silverware, reserved for his use when he came to their home for dinner. “The church was our life,” Bortz said. “We didn’t do anything that didn’t involve the church. It was our life.” When she was in ninth grade at Allentown Central Catholic High School, her religion teacher was Father Francis “Frank” Fromholzer. She didn’t know him very well; she was more acquainted with the priests who were friends of the family. At one point, Fromholzer suggested taking Bortz and her best friend on a trip to the Poconos. It wasn’t all that unusual, Bortz said. Priests were always taking kids from the parish on outings, such as roller skating or bowling; for many of the kids from working-class and troubled families, it was a treat that their own families could ill afford. While driving to the Poconos, according to testimony by Bortz and her friend to the grand jury, Fromholzer fondled the girls. In the Poconos, Bortz recalled, the priest laid out a blanket and started kissing her. He did other things. She recalled it hurt, she told the grand jury. “It was confusing,” she told the grand jury, “because – you were always told you were going to hell if you let anybody touch you. But then you’ve got father doing it...” Fromholzer, according to her grand jury testimony, continued to harass her through the ninth grade. It stopped, she told the grand jury, when she entered 10th grade and was in a different building. She didn’t report the abuse immediately. It just wasn’t something you talked about, she said. Her friend did report it to the school principal at the time. She came from a single-parent home – her mother left, leaving her in the care of her abusive, alcoholic father – and when she told the principal that Fromholzerhad molested her and Bortz, she was expelled from school and told to bring her father in for a meeting. At the meeting, the principal told her to tell her father “the made-up story you told about the priest,” she told the grand jury. On the way home, she said, her father screamed at her and beat her. When they got home, he beat her with a belt. At the time, Bortz didn’t know that her friend had told the principal about the abuse. All she knew was that her friend had disappeared, expelled from school. Years passed. In the 1980s, Bortz decided to report it. She went to a family friend, Father Anthony Wassel – his name is incorrectly spelled “Weasel” in the grand jury report – and tried to tell him what had happened when she was in ninth grade. Wassel told her he didn’t want to hear it and suggested that she “go to confession and pray for him.” She then went to Monsignor John Murphy of the St. Thomas Moore parish, with similar results. He told her, “Don’t say his name.” In 2002, after the Boston Globe’s groundbreaking reporting on abuses in the church came out, she went to law enforcement to report what happened to her. The police looked into it and referred the case to the district attorney, who, citing the expiration of the statute of limitations, declined to prosecute. She became involved in the Survivors Network for those Abused by Priests and became a sounding board for other victims, often fielding phone calls in the middle of the night from others living with the shame and anxiety from the past abuses. Then the grand jury investigation came along. And she learned that while the church wasn’t interested in what she had to say, it was interested in her. At one point, when she was trying to report her abuse to the church hierarchy, she was told to expect to hear from a private investigator. “Nothing ever came of it,” she said. “I thought they were hiring the private investigator to investigate the priest. I had no idea.” *** Among the documents the grand jury subpoenaed from the church’s secret archives was a Sept. 3, 2002, fax from the church’s attorney, Thomas Traud. After some discussion about attempting to set up a meeting with Bortz regarding her possible litigation, the document went in a different direction. The lawyer wrote that he had received information about Bortz from “an informant,” as the grand jury put it, that painted her in a less-than-favorable light. The informant told the diocese that, while in high school, Bortz had “once danced as a go-go dancer,” according to the grand jury. The implication was that she was a stripper. It was nonsense, Bortz said. She had done go-go dancing for a local radio station, wearing shorts and knee-high go-go boots. There was nothing untoward about it, she said. The informant also told the church that she believed Bortz was among the girls who had what was described as “an affair” with a coach at Central Catholic. Again, Bortz said that was not true. She said that there was a girl who had a sexual relationship with a gym teacher at the school, but it wasn’t her. The informant also told the church that Bortz had a family member who once went to jail. “Having received a report that one of their priests had violated children, the Diocese and its attorney immediately began to exchange information meant to discredit the victim with unrelated and irrelevant attacks on her and her family,” the grand jury report states. “Moreover, the fact that information that a Central Catholic coach may have been sexually abusing students was used as evidence against the victim. In reality, it is the report of yet another crime not reported to the police.” It didn’t end there. In 2004, as Bortz was pursuing a lawsuit against the church – a suit that was later dismissed because the statute of limitations had expired – Traud reported that a lawyer had told him that Bortz’s daughter was a witness in a murder case and Bortz had been involved in that case, according to the grand jury report. The lawyer wrote that Bortz could either be “a mother looking out for her child; or, maybe this is a woman who repeatedly wants her fifteen minutes of fame.” Bortz’s daughter had witnessed a murder when she was 16, and Bortz became involved to protect her while the case was going through the legal system. She declined to discuss details of the case, out of deference to her daughter, who still feels the trauma of witnessing the murder. In another letter, the grand jury reported, “Traud informed the Diocese that Julianne's husband was associated with the Christian Motorcyclists Association which Traud labeled the husband's brainchild.” Bortz assumes that was intended to imply that her husband was a member of an outlaw biker gang. “It’s ridiculous,” she said. “I don’t know what they were getting at with that.” *** She did not know that the church had looked into her background, or her family’s background, until the grand jury report came out. She was not shocked, but she was still, well, shocked. She had heard from other victims that the church dug into their backgrounds, but she had no idea that it had also dug into hers. “It really pissed me off,” she said. “They brought my kids into it. That’s just wrong.” In a statement, Bishop Alfred Schlert, who was appointed bishop of the Allentown diocese in June 2017, said, “I have always viewed victims and survivors as sincere, dignified, and extremely courageous for coming forward. I have always treated them with respect, and I always will. For those who suggest otherwise, nothing could be further from the truth.” Diocese spokesman Matt Kerr said that the church did not ask its lawyer to dig up information about Bortz and that his communications were “unsolicited.” He said, “It ended there. Nothing was ever done with the information.” The grand jury report has had some fallout for Traud. In April, he had been nominated to serve as the solicitor for the city of Allentown. The day after the grand jury report came out, the city council fired him. “Who we choose to work for us is a statement of the values and the ideals that we hold,” Councilman Courtney Robinson told the Allentown Morning Call. “I do not believe the words attributed to attorney Traud represent anything that I as a citizen or as a member of this body want our attorney or legal adviser to represent.” In a statement released to the press, Traud said, “Last night, I was removed as Allentown City Solicitor without any member providing me notice or an opportunity to be heard. I am prohibited from any other comment by attorney-client privilege.” *** The grand jury concluded, “Victims are reluctant to report to law enforcement or take any action for fear of retaliation from the Dioceses. That retaliation and intimidation takes many forms.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.