|

Pennsylvania priest-abuse report recalls 2003 crisis in Phoenix

By Michael Kiefer

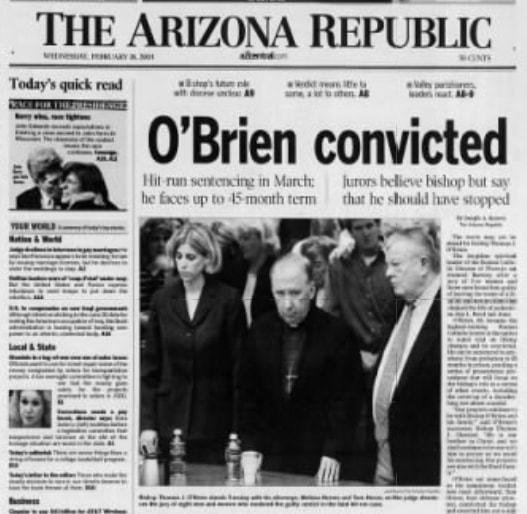

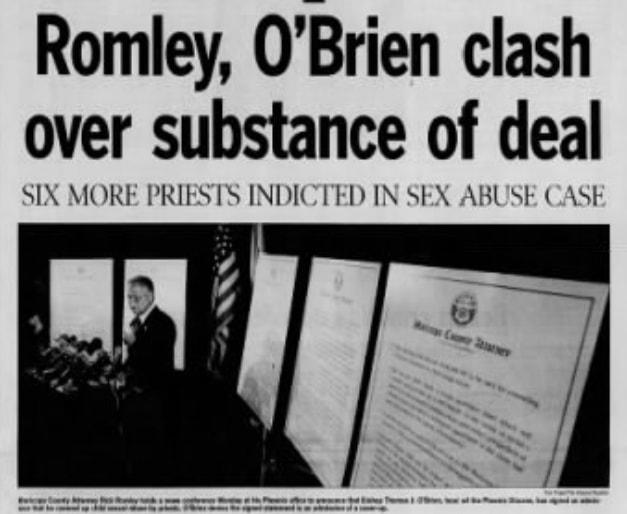

[with pdf] [with pdf] A Pennsylvania grand-jury report has reignited international interest in the history and cover-up of sexual abuse by priests, especially abuse of children. And it brought back memories of a similar crisis 15 years ago in the Phoenix diocese of the Roman Catholic Church. In 2003, former Maricopa County Attorney Rick Romley forced then-Bishop Thomas O'Brien into an admission of cover-up after an investigation that involved hundreds of thousands of pages of diocese records and the testimony of a priest who wouldn't look the other way. Six priests were indicted; two fled the country; others were sued in civil court. And the Phoenix diocese was made to accept conditions to try to prevent future abuses. O'Brien resigned within weeks of the settlement after being arrested for a fatal hit-and-run accident. He was convicted and sentenced to probation, and lived largely in seclusion in a church-owned house in Phoenix for the last 15 years. He died Sunday of complications from Parkinson's disease, according to the diocese. He was 82. A scathing grand jury reportThe Pennsylvania report, which was released July 27, spanned all but two of the state’s dioceses and profiled more than 300 priests. It resulted in only two indictments, because most of the incidents alleged were so old that the statute of limitations had already run. It uncovered a history of cover-ups and transfers rather than punishment or corrective action. “The main thing was not to help children,” it says in its preamble, “but to avoid ‘scandal.’ That is not our word, but theirs; it appears over and over again in the documents we recovered.” Among the findings were that church officials referred to sex allegations with euphemisms, investigated them in-house, allowed priests to perform self-evaluations of their actions, housed the offenders, transferred them to other assignments where they committed the same bad acts, and above all, failed to report to police. The grand jury report also published the names and records of the offenders and those who covered up the abuses, but again, most of the alleged crimes had occurred too long ago to prosecute. Response to the report was viral and echoed in the Vatican. Pope Francis, in a letter to Catholics everywhere, wrote, “We showed no care for the little ones. We abandoned them.” Over the past two decades, there have been similar priest scandals around the country and the world — in Ireland in 2009, and most recently in Chile, whose bishops all tendered their resignations, and Australia, where another cardinal will face trial for sexual crimes. In July, the former bishop of Washington, Theodore McCarrick, resigned from the College of Cardinals after being accused of sexually abusing juveniles and adult men. The cleric who replaced him in that position, Cardinal Donald Wuerl, was named in the Pennsylvania grand jury report as someone who covered up abuse. Wuerl canceled his attendance at an upcoming international Catholic meeting about families, where he was to deliver a keynote address and appear alongside the pope. Bishop Thomas Olmstead issued a pastoral letter to the Phoenix diocese, over which he presides, expressing “our own deep level of sadness and anger about the recent revelations,” especially in regard to McCarrick. Arizona allegations surfaced years agoFor Phoenix, this is déjà vu. It comes 15 years after former Maricopa County Attorney Richard Romley concluded his own investigation that came to similar findings, except those conclusions led to six criminal indictments of priests and countless lawsuits. In 2003, former Bishop O’Brien was granted immunity from prosecution after signing a document admitting his part in cover-ups. “I acknowledge that I allowed Roman Catholic priests under my supervision to work with minors after becoming aware of allegations of sexual misconduct,” said the settlement agreement. “I further acknowledge that priests who had allegations of sexual misconduct made against them were transferred to ministries without full disclosure to their superiors or to the community in which they were assigned.” In exchange for the admission, the diocese entered agreements with Romley to appoint a curator to oversee internal church investigations and provide about $700,000 for treatment for victims. Now the Phoenix diocese maintains a public listing of living priests who have been suspended because of sexual abuse; it comprises 35 names, many of whom were outed in the 2003 investigation. “Pennsylvania’s grand jury report is extremely troubling and provides a sobering reminder of the exhaustive investigation former Maricopa County Attorney Rick Romley conducted of the Phoenix Diocese more than 15 years ago,” said Katie Conner, spokeswoman for the Arizona Attorney General’s Office. “At this time, we can’t comment publicly on possible actions by this office, but if similar allegations exist in Arizona, we encourage victims to report incidents to local law enforcement. Anyone who abuses a child needs to held accountable, no matter how long ago the abuse took place.” There is no statute of limitations on sexual child-abuse crimes in Arizona. Cindy Nannetti, who headed the sex crimes unit at the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office at the time of the priest investigation, put it more bluntly. “What the hell has Pennsylvania been doing all these years?” she asked. “My question to them would be, ‘What took you so long?’” Media uncovers sexual allegationsIn January 2002, the Boston Globe began publishing stories about pedophile priests. That series went on to win a Pulitzer Prize and was memorialized in the 2016 film, “Spotlight.” A month later, The Arizona Republic began reporting on sexual allegations against priests in Tucson, and by May, the coverage, led by reporters Joseph A. Reaves and Michael Clancy, had expanded to include the Phoenix diocese. Some of the priests had served both in Boston and Arizona. And at about the same time, investigations played out in Philadelphia. Romley didn’t recall whether the Phoenix investigation started with the media reports. “We had indicted priests before, so we were cognizant of it,” he said. But the tips poured in because of the coverage. Prosecutors and investigators combed through hundreds of thousands of church documents and the personnel records of more than 70 priests, but those records were not obtained easily. The church lawyers challenged subpoenas. A priest testifies before grand juryAmong the grand jury witnesses who made the case was a former priest named Joseph Ladensack, who had fallen out of favor with O’Brien for reporting pedophile priests to the police. Earlier this year, Ladensack published a first-person account about his adventures and struggles as a soldier in Vietnam and as a priest in Arizona. The book, Hard to Kill, was authored by Reaves, the former Republic reporter. It opens with an anecdote about Ladensack being called to the home of a friend who was distraught because he had walked into his son’s bedroom to find a priest performing oral sex on the 15-year-old son. Ladensack called police, who took a report from the boy’s parents. Then he called O’Brien. “O’Brien blew totally out of control,” he wrote. “The bishop ordered me to go back to the (family’s house) and have them recant the story to the police,” he wrote. Ladensack took his knowledge to Romley. Indictments handed down in PhoenixUtlimately, the results of the Maricopa County Attorney's investigation mirrored those elsewhere. Pedophile priests were rarely punished; they were moved from parish to parish, where they committed the same acts. At worst, they were put up in church housing and supported rather than evicted. O’Brien, Clancy said, “was following the game plan that everyone else was.” As a result of the county attorney's investigation, six priests were indicted. Two fled; one to Ireland, which refused to extradite him, and another to Mexico. Romley said he wrote a letter to a cardinal at the Vatican who had authority over the two fugitive priests. He asked the cardinal to order them to return for prosecution and promised a fair trial. “That document came back to me: 'Return to Sender,'” Romley said. “But you could see that it had been opened. There was a clean cut that had been taped over. So it went all the way back to Rome.” Romley was an active Catholic at the time, and the investigation took a personal toll. One of his own relatives called him and became irate that he was looking into criminal charges against the bishop. “He’s a good man,” she told him. Romley answered, “But somebody’s got to protect the children.” “From a personal standpoint, I had to reconcile some things,” he told The Republic. “The church has done a lot of good, but the priests were the problem.” A story that rattled reporters, investigatorsAnd just as the stories of abuse and cover-up had been tough on the investigators and prosecutors, it was hard to report. “I sat with grown men who wept when they abandoned long years of silence to tell me how they had been raped as children by priests they once honored,” Reaves wrote in the foreword to Ladensack’s book. “Every day I grew angrier and darker as I learned more about the malignancy rotting inside the church I once revered as an altar boy … ” As in the movie “Spotlight,” there was pushback from the church and the faithful, even inside The Republic newsroom. In the book, Reaves writes about editors who tried to block or downplay stories. Clancy registered the same resistance. Both are now retired. It did not go well for O’Brien, either. Just a month after signing his admission, he fled the scene of an accident, striking and killing a man, and then hiding his car in the garage of his church-owned residence and refusing to meet with police. He resigned as leader of the diocese after his arrest. Then he went to trial and was found guilty, sentenced to four years' probation. Now in his 80s, he is living in that same house. Memories, scandal lingerThe diocese provided the following statement to The Republic on Friday. "The Diocese of Phoenix has made great strides in fulfilling our promise to protect children, educate our communities, and bring healing to those who have suffered abuse. In light of recent abuse scandals, now is an important time for the Church to recall what has been learned, to keep in prayer those who are victims, and to recommit ourselves to vigilance in our Catholic community to protect our children from the evils of abuse." The statement adds that the diocese has instituted intensive screening of all employees, whether priests, deacons or volunteers; a zero-tolerance policy; "safe environment" training for students; a board of laymen to evaluate allegations; and a published list of those priests or other employees with credible accusations against them. Not everyone believes the problem has gone away. "The cover-up of clergy sexual abuse and clergy sexual misconduct remains a problem because Bishops and other leaders in the Chancery are focused more on protecting the authority, reputation and wealth of the diocese than they are about protective children," Robert Pastor, a Phoenix attorney who has active cases involving alleged sexual abuse by priests, said in a statement. "In my opinion, for there to be real change, lay Catholics must demand transparency from the Bishop and stop the culture of clericalism." The full extent of the abuse, however, is difficult to track. There were no mandates on the church in Phoenix to report abuse to the authorities. The scandal was that the church was doing the opposite. By 2003, O'Brien admitted to sheltering at least 50 priests accused of sexual abuse, often shuffling them around to different parishes across the state. As Nannetti points out, the children themselves were not reporting until they were adults. Some went to police, others sued, many entered sealed settlements with no public reckoning of what was paid and what admissions were made, if any. "Victims of sexual abuse often suffer in silence; wondering if they are alone; wondering if their friends and classmates were also sexually abused," Pastor said. "Exposing clergy sexual abuse the way the attorney general for Pennsylvania did is an important step because it may help other victims discover that they were not alone, that the Catholic Church covered it up and that the Catholic Church is not above the law," he said. "Unfortunately, it takes a courageous prosecutor to undertake such an investigation." The scandal comes back persistently. As recently as 2017, O’Brien was named in a civil lawsuit that accused him of sexually abusing the plaintiff between 1977 and 1982 while he was in second through fifth grades. “Ours was not the first lawsuit identifying him as a perpetrator,” said Tim Hale, a California attorney who specializes in priest sexual abuse cases, and one of the attorneys who brought the present case against O’Brien. The lawsuit names 60 other priests affiliated at one time with the Phoenix diocese as being complicit. The case has been slowly working its way through court. Hale, compiled that roster from the 35 names on the list published by the diocese, another list turned over as evidence in a case in Gallup, New Mexico, that identified priests who had served in Arizona, and from a website called bishopacountability.org. That was a far as Hale could go in putting numbers to the problem in Arizona, but the abuse was global. “The reality is that most survivors of child sexual abuse never come forward, and those who do, it takes 20, 30, 40 years,” Hale said. “There are so many stones left unturned in this scandal,” he said. “It is way too soon to say, ‘Mission accomplished.’”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.