|

How other states' lawmakers have dealt with sex abuse legislation, and why Pennsylvania's may be behind

By Michelle Merlin And Carol Thompson

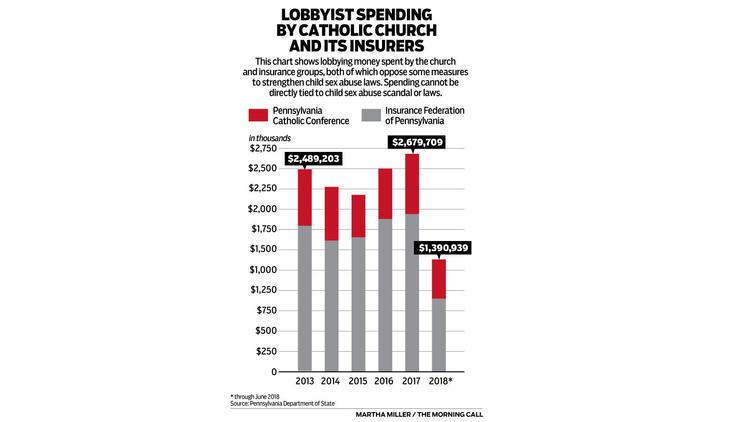

Bills to strengthen Pennsylvania child sex abuse laws are introduced in the Legislature with almost religious regularity. The Morning Call reviewed 28 filed since 2013 — 15 in the 2015-2016 session alone. But none has gained traction, despite the outcry over child sex abuse scandals in the state’s Catholic diocese and the Penn State University football program during the Jerry Sandusky era, which broke in 2011. Just two of those 28 bills came up for a vote; politicians in the state House and Senate have been unable or unwilling to act on the others. Advocates for change want to allow victims who have aged beyond the current statute of limitations to be able to retroactively file civil lawsuits against their abusers. But they face pressure from the insurance industry and the Catholic church, both of which oppose changes that could lead to expensive lawsuits, additional embarrassing disclosures and damaging publicity. Other states have acted to change their laws, with mixed results. Some dioceses have declared bankruptcy, but authorities also have discovered new allegations of abuse in doctors’ offices, schools and facilities for disabled children. Pennsylvania’s laws are among the worst in the country in protecting children from sex abuse, according to a ranking from Child USA, a Philadelphia think tank dedicated to ending child abuse and neglect. The nonprofit gave Pennsylvania a score of 5 out of 10 in its latest ranking of states’ child sex abuse statute of limitation laws. Ten other states also earned a 5. Only five ranked lower. In Pennsylvania, victims can raise criminal complaints until they are 50 and civil complaints until they are 30. That’s a short time frame, said Marci Hamilton, CEO of Child USA and a University of Pennsylvania professor, describing Pennsylvania’s laws as “decidedly mediocre.” The average age of a victim who is ready to come forward is 52, she said. Forty-one states have eliminated the criminal statute of limitations on child sex abuse claims entirely since The Boston Globe in 2002 revealed widespread child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. “In Pennsylvania, the statutes of limitations have been so short for so long that the vast majority of victims are shut down,” Hamilton said. Since the Boston Globe report, state lawmakers around the country have pushed for legislation extending statutes of limitations. Some bills call for opening a “window” so victims now deemed too old could still bring cases. The recent Pennsylvania grand jury that investigated the sexual abuse of children by priests in six Catholic dioceses, including Allentown, recommended a window that would give older victims a second chance to sue. Hamilton said the ideal legislative scenario can be found in the U.S. territory of Guam. In 2016, Guam completely removed the civil and criminal statute of limitations for child sex abuse cases in the past and future. That move came five years after lawmakers passed a bill instituting a two-year window for any old cases, and eliminating a statute of limitations for future child sex abuse cases. Thousands of people claiming to be victims have come forward in states that passed legislation strengthening measures against child sex abuse, including Delaware, California, Minnesota and Hawaii. Delaware earned a perfect score in Child USA’s ranking. In 2007, the state eliminated civil and criminal statutes of limitations and opened a two-year window for past victims to bring cases. “The biggest payoff in Delaware was that we learned about a very abusive pediatrician,” Hamilton said, referring to Earl Bradley, a serial pedophile who was convicted of abusing more than 100 children. Church abuse victims also came forward after the Delaware law was passed. After settling victim lawsuits for $77 million, the Wilmington Diocese filed for bankruptcy protection in 2009, which led to layoffs, property sales and near liquidation of a fund that was used to defray capital costs for local churches, spokesman Bob Krebs said. The bankruptcy did not require parishes to close. Bankruptcies can lead churches to sell property, end charitable programs and close schools, said Pennsylvania attorney Matthew Haverstick, who represents the Pittsburgh and Greensburg dioceses. “There are real and palpable effects of a bankruptcy on the Catholic community,” he said. Thomas Neuberger, a lead attorney in 100 cases filed after Delaware changed its laws, said such reforms provide victims the opportunity to seek justice. “It’s only the key to the courthouse door,” he said. “They still have to prove a case.” Creating a window to allow child sex abuse victims to file dated claims is a part of many of the bills that have stalled in Pennsylvania. It’s a sticking point for Haverstick, who argues it would be unconstitutional to allow someone to file a lawsuit after a statute of limitation had expired. Joe Scarnati, president pro tempore of the state Senate, and the Insurance Federation of Pennsylvania, echoed his claim. Sam Marshall, federation president and CEO, said such legislation would create a retroactive liability for insurers without allowing them to cover it. “An insurer cannot hold a reserve for potential claims once a statute of limitations has run [out] — so retroactively extending that limitations period … creates liability for which an insurer could not charge a premium nor establish a reserve,” Marshall said in a statement. Scarnati said in a statement he would favor changing the state constitution to allow for retroactive claims, but pointed out doing so is “an extended process [that] has no absolute certainty.” Neuberger, the Delaware attorney, said supreme courts in states that created filing windows have held them as constitutional. “These legal questions shouldn’t be decided in the Legislature, that’s just an excuse,” he said. The number of cases brought during states’ open-window periods has been relatively low, Hamilton said. In Delaware, there were about 1,175 civil cases; in California, 1,150 cases; and Minnesota, 1,000 cases, according to Child USA. Hamilton estimated Pennsylvania could see 1,000 to 1,500 cases if it opened a window. She said the bills are important because they help victims feel validated. “The only reason you’d vote against it at this point is politics,” Hamilton said. That may be what’s stopping Pennsylvania lawmakers who, despite numerous attempts, have not strengthened the state’s sex abuse laws since 2006. In 2002, legislators unanimously voted to extend the statute of limitations for civil child sex abuse complaints until a victim is 30 years old — a decade older than the previous law. In 2006, they increased the age for the criminal statute of limitations to 50 years old and required people who work with children — whom the state recognizes as mandated reporters — to report all suspicions of abuse, not just when the child disclosed abuse. Since then, repeated attempts from Pennsylvania legislators to strengthen the state’s child sex abuse laws largely have fallen flat. The bills typically focus on a few core areas: extending or eliminating the statute of limitations for victims of child sex abuse to bring civil and criminal charges; opening a window of one to two years for victims of past abuse to bring charges; allowing child sex abuse victims to sue state and local governments; and adding to the list of mandated reporters. Only two of 28 bills introduced since 2013, a year after Sandusky’s conviction in Centre County, and examined by The Morning Call have gotten a vote, and only one has been voted on by both the state House and the Senate. The House passed a bill in 2016 that would eliminate the criminal and civil statute of limitations. It also included a two-year window for past victims to file cases. But the Senate stripped out the window provision, and the House never picked the bill back up. Lobbyists for Catholic groups and the insurance industry, which covers Catholic churches, have been fighting those bills, Hamilton said. Since 2013, the Pennsylvania Catholic Conference has spent more than $3.7 million on lobbying, state records show. The Insurance Federation of Pennsylvania spent more than $9.7 million, The Morning Call calculated. The public can’t determine how much of that spending targeted child-abuse legislation; the state’s lobbying disclosure rules do not require such specifics. Haverstick, who represents two dioceses, said the church supports some measures to strengthen child sex abuse laws in the state — eliminating age limits for filing civil and criminal complaints, and strengthening mandated reporting policies. He voiced support for one of the bills introduced since 2013: Senate Bill 261, which would have extended the statute of limitations for child sexual abuse to allow victims to file civil claims until they are 50 years old, and abolished the statute of limitations on criminal prosecution of child sex assault cases. It does not provide a window for victims to retroactively sue. That bill was stalled in 2017 after the House amended it. Originally, the bill called for eliminating the civil and criminal statutes of limitations on child sex abuse. The Senate’s version struck the measure eliminating the civil statute of limitations. It never moved back to the House for a second vote. Lehigh Valley lawmakers' bills Sen. Lisa Boscola, D-Northampton, has been the primary sponsor or sponsor of eight pieces of child sex abuse legislation over the last five years, the majority of which call for an elimination of criminal and civil statute of limitations for child sex abuse. Sen. Pat Browne, R-Lehigh, sponsored legislation that would preclude grand juries from criticizing public officials, witnesses and others not charged with a crime but whose actions, or lack thereof, may have been a contributing factor to the crime. The bill would forbid prosecutors from naming anyone or any organization not charged with a crime. The bill also would mandate that judges provide “reasonable notice” to anyone affected by the court-approved disclosure of a grand jury record. Browne also sponsored three bills that eliminated the statute of limitations on sex abuse cases involving children under 14. Rep. Robert Freeman, D-136th, sponsored a bill to eliminate the statute of limitations on child sex assault victims and to allow a two-year window for past victims to file suits. Rep. Marcia Hahn, R-138th, sponsored a bill to eliminate the statute of limitations on criminal prosecution of child sex assault. Rep. Mike Schlossberg, D-132nd, sponsored a bill to allow victims to file child sexual assault lawsuits until they are 50 years old, create a two-year window for past victims, and allow victims to petition a court to re-open previous civil suits. Contact: mmerlin@mcall.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.