Brooklyn Diocese Ignored Protocol and Unwittingly Accepted Priest Accused of Abuse

By Taylor Dolven

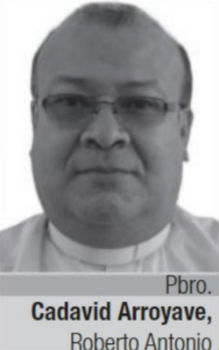

For five years, Father Roberto Cadavid led mass, heard confessions and guided children through the confirmation process as a priest at Catholic churches in Brooklyn and Queens, until he returned to his native Colombia in the summer of 2017. It wasn’t until 10 months later that his old parishioners were informed of why he left the United States: children in Colombia had come forward to accuse Cadavid of sexual abuse. A review of records and correspondence by Gothamist shows that the Diocese of Brooklyn bypassed its own safety protocols to hire Cadavid in 2012. When the Diocese of Medellin eventually informed Brooklyn about Cadavid’s long history of alleged abuse in June 2017, the diocese let Cadavid go quietly. By the time Cadavid arrived in Brooklyn in December 2012 to start his work here, at least four young boys had come forward accusing Cadavid of abusing them, starting in 2005 when he was director of a school half an hour outside of Medellin. Cadavid was moved from church to church around Medellin as abuse allegations at his new assignments would emerge. One victim said Cadavid paid him 88 million Colombian pesos in 2009 (about U.S. $46,000) to remain silent about the abuse. “We are still in the process of getting all the testimonies from victims, their families and witnesses,” said attorney Sara Goznalez, who is representing the six people, five of them still minors, who have accused Father Cadavid of abuse. “Some of the families are very afraid to come forward, so we are helping them through that. The church is very powerful in Colombia.” According a 2010 audit of diocese protocols for hiring international priests conducted by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), the Diocese of Brooklyn requires recommendation letters from foreign bishops to include a specific assurance that the priest has never been charged with a crime, and that the priest “has not manifested behavioral problems in the past that would indicate he might deal with minors in an inappropriate manner.” When the Bishop of Medellin, Ricardo Tobon, wrote to the Bishop of Brooklyn, Nicholas DiMarzio, in November of 2012, he gave his blessing for the transfer. But his short letter included no such assurance language. The Diocese of Brooklyn hired him anyway.

“This is another example of why the institution can’t police itself and the public has a reasonable fear that they won’t follow their own safety policies,” said Patrick Wall, a former priest and church sex abuse survivor advocate. “We’ve supposedly had a zero-tolerance policy since 2002.” After the Boston Globe’s 2002 Spotlight investigation of sexual abuse, the USCCB created the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People, which called on church leaders to more thoroughly vet priests in order to prevent sexual abuse. In 2003, the USCCB published guidelines for vetting international priests, acknowledging the unique difficulties of conducting cross-border background checks. Despite the attention to more thorough vetting, a 2007 USCCB audit found that half of the credible sexual abuse allegations from children that year who were still minors were made against international priests. In 2008, USCCB began to publish annual audits of each diocese’s protocols for hiring international priests. The USCCB stopped publishing these audits after 2010. That year, one in five priests serving in the U.S. were visiting from other countries, including 96 in Brooklyn. At least six international priests had sexually assaulted minors in Brooklyn prior to Cadavid’s arrival in 2012, according to a website that tracks allegations of abuse against priests. Twenty-two dioceses out of 183 audited in 2010 require recommendation letters from bishops to include an assurance that the priest has never been inappropriate with children. In a March 2018 interview with W Radio in Colombia, Tobon, the Bishop of Medellin, said he had no knowledge of Cadavid being in the U.S. and did not recommend him for the transfer to Brooklyn because he suspended Cadavid in 2012, “immediately” after he learned of abuse allegations against him. “I took him out of the parish and I suspended him, when the information came to me. I presented the information to the Holy See and that's how it ended,” Tobon said in the interview. But Bishop Tobon’s claims are contradicted by his own correspondence with Bishop DiMarzio, the Bishop of Brooklyn, which Gothamist has reviewed. Tobon’s short November 2012 letter recommending Cadavid said, in Spanish, “I appreciate the reception and accompaniment that you can give him. He has permission from me to serve in the mission that you entrust him with.” The letter appears on Archdiocese of Medellin blue and yellow letterhead and includes Tobon’s signature and stamp. In December 2012, Father Cadavid began working at Our Lady of Angels Church in Bay Ridge. He was made head priest at St. Rita’s Catholic Church in Long Island City in June 2013.

When Bishop DiMarzio requested to extend Cadavid’s time in Brooklyn in November of 2014, Tobon sent another official letter three months later that failed to mention that he had suspended Cadavid in 2012 because of allegations of sexual abuse. “If your excellence finds it convenient, I don’t see any obstacle to responding affirmatively to this solicitation, hoping that Father Cadavid is for you a worthy help,” Tobon’s letter said. That year, the USCCB again cautioned dioceses about ensuring international priests do not have histories of abuse. "A significant number of allegations continue to involve international priests. Dioceses should take note of this and ensure they are utilizing the appropriate methods for evaluating their backgrounds," the 2015 report said. Finally, on June 22, 2017, Tobon responded via email to a letter from DiMarzio in which DiMarzio thanked him for Cadavid’s service. “First of all, I want to express my surprise about the information that Cadavid was practicing ministry in your diocese,” the letter said, in Spanish. “He, in effect, has been suspended since March 14, 2016, by means of the attached decree, a suspension that was imposed due to the accusation of sexual abuse of a minor.” The decree, reviewed and transcribed by Gothamist, said Cadavid was credibly accused of sexually abusing minors. The next day, on June 23, 2017, the Diocese of Brooklyn responded to Tobon saying they suspended Cadavid. “The question is why wasn’t the Diocese of Brooklyn notified of his suspension before? Please let us know,” the letter said, in Spanish. Tobon did not respond to this request. The Diocese of Brooklyn sent out an alert to leaders at each parish in Brooklyn saying Cadavid was suspended, but did not mention that the suspension was because of alleged sexual abuse. Tobon did not respond to multiple requests for comment and for clarification about when he suspended Cadavid and why he twice recommended Cadavid to the Diocese of Brooklyn. His press secretary, Mauricio Agudelo, and deputy, Oscar Alvarez, also did not respond to multiple requests for comment. “He was lying and covering up for this priest,” said journalist Juan Pablo Barrientos, who conducted the interview for W radio, and who has written a series of stories on the church’s efforts to shield priests accused of abuse for outlets like El Tiempo. Barrientos says that since the interview aired, he’s been unable to get Tobon to answer any questions. “He was caught in a lie.” The Diocese of Brooklyn waited 10 months to tell parishioners about Cadavid’s alleged history of sexually abusing minors, finally informing them on April 8, 2018, one month after the W Radio investigation about Cadavid was published in Colombia. Diocesan officials spoke with families who were particularly close to Cadavid at St. Rita’s and Our Lady of Angels and urged anyone with an allegation to contact the diocese hotline. In a statement, the Diocese of Brooklyn says they “deeply regret” that Father Cadavid was allowed to minister there. “The letters from the Archbishop never indicated that there were any allegations against Cadavid and led us to believe that there was nothing in his background that would prevent him from ministering here,” the statement reads, adding that they conducted a background check and that Cadavid passed. Adriana Rodriguez, a spokesperson for the diocese, added that the diocese now requires yearly affidavits from bishops assuring that international priests working for the Diocese of Brooklyn have never acted inappropriately with minors. She declined to comment on when the new policy was instituted and if it applies retroactively to international priests already hired by the diocese. Greg Burke, the director of the Vatican press office, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. In Cadavid’s August 2012 letter expressing interest in coming to Brooklyn, he named two priests from Colombia who were working in Brooklyn and recommended him: Luis Fernando Laverde and Reinaldo Saldarriaga. Laverde is now a priest at Blessed Sacrament Church in Cypress Hills; he declined to comment. Saldarriaga worked in the tribunal of the diocese, but has since left. The Diocese of Brooklyn declined to comment on whether the diocese consulted these priests before hiring Cadavid. Cadavid did not respond to multiple requests for comment. His WhatsApp profile picture reads, in Spanish, “Sometimes it’s not worth it to be sincere, people only hear what they want to hear.” Cadavid has not been charged with a crime in Colombia. W Radio confirmed in September that 37 priests accused of abusing minors in Colombia have been reported to the federal prosecutor. Fourteen cases have been closed, seven have resulted in convictions, and 16 are pending. Gonzalez, the attorney for Cadavid’s accusers, said that she is still collecting evidence to bring to prosecutors and that the victims also intend to bring a civil lawsuit against the archdiocese. “We have evidence of the dates that some of these victims were hidden inside the parishes, spending several days there at a time away from their families,” Gonzalez said. “We have their parents’ testimonies.”

So far the Diocese of Brooklyn has not received any allegations of abuse against Cadavid during his time in Brooklyn. No criminal complaints have been made to the New York Police Department regarding Cadavid, according to several records requests. Advocates for sexual abuse survivors said it is rare that they come forward while they are still minors. Many go on to suffer from mental health disorders and substance abuse. In New York victims of child sexual abuse must come forward before they are 23 years old if they want to sue the priests who abused them. The New York state assembly considered the Child Victims Act to raise the age limit last year, but it was defeated. The Catholic church lobbied against it. Last year the Diocese of Brooklyn announced a compensation fund for victims of clergy sexual abuse that allows older victims to settle with the church. So far, 474 victims in Brooklyn have applied for settlements through the program, and 374 have received settlements, according to the New York Times. After a Pennsylvania grand jury report published in August detailed decades of sexual abuse by more than 1,000 Catholic priests in Pennsylvania, the New York State Attorney General’s office launched an investigation by subpoenaing all eight Catholic dioceses in the state. The attorney general’s office would not comment on whether Cadavid’s case is within the scope of its investigation. On a recent Sunday at St. Rita’s, parishioners filed out of the 9:30 a.m. Spanish mass down the steps of the tall, red brick church, and congregated by two long tables covered in wooden biblical figurines for sale. Everyone remembers “Padre Roberto.” One parishioner who did not want to share his name said Cadavid helped him through a time of trouble in his marriage. His son remembers Cadavid teaching catechism classes and being close friends with the church’s Director of Faith Formation, Helen Foster. Foster said she could not speak about Cadavid for this story. Another parishioner, Maura Martinez, said Cadavid helped her teenage daughter navigate her trauma after a cousin was murdered. “He talked to her, he prayed with her, and I was always in the room,” Martinez said. “He was never alone with her.” Carmen Quiroz said her children were servers who worked closely with Cadavid during mass. Earlier this year when the diocese told her Cadavid left because of sexual abuse allegations, she spoke to her kids to make sure he hadn’t hurt them. “Thank goodness he never disrespected them,” she said. Lynda Arroyo, who has been attending St. Rita’s for about three years, said Cadavid always gave her a bad feeling. “He gave a weird mass, he made jokes, he wasn’t very serious,” she said “If you’re suspended and you’re still blessing people and giving mass...He was a fraud.” Arroyo said Cadavid told parishioners that he needed to return to Colombia to care for his sick mother and remembers him asking for goodbye gifts in the form of cash. All the parishioners interviewed said there was a going away party planned for Cadavid at St. Rita’s, but he left urgently a few days before it was scheduled. “We’re all left wondering if it’s true or not,” said a teacher who worked with Cadavid who did not want to share her name. In a 2015 interview with the Spanish language website for the Diocese of Brooklyn, Cadavid said he came to Brooklyn for “spiritual renewal.” “For me it has been a great spiritual renewal, pastoral, because a lot of times changes can be traumatic, but necessary,” he said. “Perhaps one has regret and nostalgia, because one bonds with the community, but changes are important because they bring renewal.” Last year, the Diocese of Brooklyn posted names of 13 priests on its website who have been accused of sexually abusing minors and have been laicized, the most serious punishment in Catholicism. In the interview with W Radio earlier this year, Tobon said he referred the sexual abuse allegations against Cadavid to the Vatican after suspending him in 2012, and that he was no longer a priest. The Diocese of Brooklyn has not updated their published list to include Cadavid.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.