|

“They lied”: Archdiocese of Denver removed priest after seminarian’s abuse allegations, but didn’t move to defrock him

By Elise Schmelzer

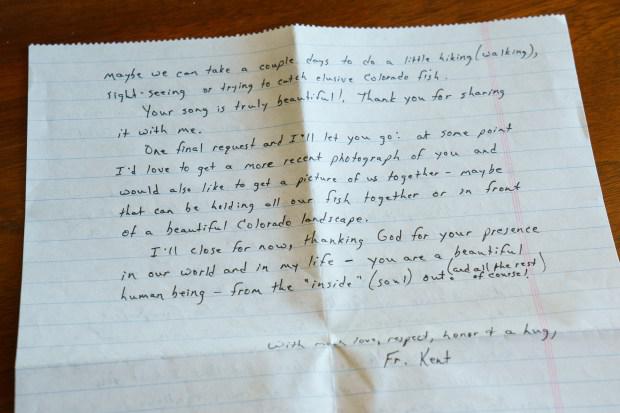

Former seminarian says he feels betrayed by the church, lied to by those he knows in its leadership A Catholic priest in Denver accused of having sexually abused a young seminarian over the course of four years in the early 2000s was placed in a local church with a school after the Archdiocese of Denver learned of the allegations. The clergyman, Kent Drotar, lost permission to work as a priest less than two months later and was removed from his post at Notre Dame Catholic Church in southwest Denver after a disciplinary team found the allegations against him credible, as first reported by The Philadelphia Inquirer on Monday and confirmed by The Denver Post. Stephen Szutenbach, now 37, studied at St. John Vianney Theological Seminary in Denver from 2001 to 2004, and said Drotar — then the vice rector at the seminary — repeatedly made unwanted sexual contact with him. The abuse began in the summer of 2000 when Szutenbach was 18 and worked as a groundskeeper at the seminary after graduating from Conifer High School, Szutenbach told the Post in an interview Monday. The archdiocese’s handling of the abuse reports has more deeply affected Szutenbach than the abuse itself, he said. He feels betrayed by an institution that he once considered committing his life to and lied to by those he knows in church leadership. He is angered by the church’s failure to pursue the lengthy process to officially remove Drotar from the priesthood. “He’s still a priest,” Szutenbach said. “In the eyes of the church, by church law, the man is still Father Kent Drotar.” Drotar did not respond to messages left Monday by the Post on his cellphone or work phone, and previously declined to speak with the Philadelphia newspaper. The Archdiocese of Denver temporarily suspended Drotar after learning about the allegations in 2007, but later reinstated the priest for less than two months that summer at Notre Dame Catholic Church, which runs a school of the same name, archdiocese spokesman Mark Haas said Monday. The archdiocese later fully restricted Drotar from practicing as a priest after a disciplinary panel found Szutenbach’s allegations credible, but the diocese never asked the Vatican to officially defrock Drotar. But archdiocese leadership said Monday that the church followed protocol when it learned of Szutenbach’s allegations. “You can look back and nitpick at every little thing that happened, but the point is the process worked,” Haas said. “The priest is no longer a priest.” The Philadelphia Inquirer published its story less than three months after Denver Archdiocese leaders joined other church officials in calling for an independent investigation into sexual abuse allegations against Catholic priests and the church’s attempts to cover them up. The Catholic Church has dealt with decades of scandal as investigations have found hundreds of priests across the globe who sexually abused minors in their churches. The findings prompted the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops to establish a comprehensive charter about the crimes in 2002, a document that has been updated repeatedly as religious leaders continue to grapple with the issue. Denver Archbishop Samuel Aquila on Monday attended a national conference for bishops in Baltimore, where attendees were scheduled to vote on new proposals to tackle sexual abuse — but were told not to do so by the Vatican. It was the publication by Colorado Public Radio of an interview with a leader in the Denver archdiocese discussing the local response to the ongoing scandal that was one of the factors that prompted Szutenbach to approach the Philadelphia newspaper about his experience. In the CPR interview, the archdiocese’s vicar general, Father Randy Dollins, said the archdiocese had no new reports of sexual abuse of minors by a priest since 2002. “That really rubbed me the wrong way,” Szutenbach said. “It was a lie. It may have been technically the truth, but it’s not the spirit of the truth.” ‘I felt guilty’Szutenbach first met Drotar at Catholic youth retreats as a high schooler, he said. Szutenbach’s family was deeply Catholic — attending Mass at least once a week and often praying the rosary in the car — and the priest attended the retreats in his role as the archdiocese’s vocation director, charged with recruiting young people to the priesthood, Szutenbach said. Drotar started to build a friendship with Szutenbach beginning at a 1999 retreat at the seminary as the teen continued to consider studying for the priesthood. The priest became friends with Szutenbach’s family and posed himself as a father figure to the young man, Szutenbach said. “At first I thought it was a normal thing he would do for any prospective candidate,” Szutenbach said. “I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t know what was normal for that kind of relationship.” Szutenbach was flattered by the attention, he said, and knew that impressing Drotar was important in securing his admission to the seminary. When Szutenbach took the job working on the seminary grounds, Drotar would invite him to lunch in his second-floor apartment, which had air conditioning, Szutenbach said. Drotar started becoming increasingly touchy with Szutenbach during the lunches, Szutenbach said. But the first blatant sexual overture occurred when the two traveled to Gunnison for a weekend fishing trip during the summer of 2000. During the last night of the trip, Drotar climbed into the sleeping teen’s bed in their shared motel room and started touching him, Szutenbach said. He told Drotar to stop and said the fondling was “definitely unwanted.” But the priest remained in Szutenbach’s bed until later that morning, when he offered to hear the teen’s confession, Szutenbach said. The teen had never kissed anybody before and felt guilty. A sick feeling settled in Szutenbach’s stomach for the entire 3½-hour drive back to Denver that day. “I felt terrible. So, so terrible,” Szutenbach said Monday. “I felt guilty, like I had been a temptation to him.” Szutenbach’s life returned to a semblance of normal a few days after the trip, though he tried to deflect the priest’s invitations to his apartment with suggestions that they take a walk instead, he said. He didn’t tell anybody about the abuse. Szutenbach left Denver in August 2000 to attend seminary in Minnesota, where Drotar once visited him and rented a Minneapolis hotel room for the night for the two men after driving Szutenbach to visit nearby grandparents. “And the same thing happened again,” he said. In search of more serious academics, Szutenbach returned in 2001 to the seminary in Denver, where he stayed for three years. Once he returned to the campus, Drotar’s sexual advances resumed and intensified, worsened by the fact that the priest lived in the same building as Szutenbach at the seminary. The priest forced sexual contact on the seminarian dozens of times, Szutenbach said. As Szutenbach attempted to be more assertive in avoiding the abuse, Drotar became more manipulative, Szutenbach said. The priest would tell the young man that he relied on his support, and, Szutenbach said, threatened to kill himself on multiple occasions in response to Szutenbach’s attempts to distance himself, especially as the young man considered leaving the seminary. “If we’re both in the priesthood there’s a bit of a mutual destruction pact,” Szutenbach said. “If I say something, it’s equally damaging to me as to him.” Szutenbach left St. John Vianney in 2004 for a variety of reasons, he said, including the abuse. But mostly he did not not want to lie about being gay for the rest of his life as the priesthood would require, he said. Szutenbach moved to Florida in 2005 to attend architecture school. He remained an active Catholic, even sponsoring other gay men to join the church. He and Drotar spoke sometimes, but Szutenbach tried not to think about the priest. He hadn’t thought of himself as a victim, he said, and still felt partly culpable for the abuse. “I was kind of ashamed of it, as a lot of people are, especially as a guy,” he said. It wasn’t until he met with one of his former teachers at the seminary while visiting Colorado in 2007 that he realized the full scale of what had happened to him. He explained the abuse to his former teacher, who reported it to the seminary along with another employee there, he said. He didn’t want to hurt the Catholic Church, he said, and trusted that the archdiocese would do the right thing and immediately release Drotar from the ministry. “I expected the people I knew and trusted — I knew all of them personally — I expected them to be men of faith and men of integrity,” he said. “Instead, they lied.” Speaking upThe archdiocese became aware of Szutenbach’s allegations in January 2007 after the two seminary employees reported them, according to a Nov. 7 letter compiled by the archdiocese in response to questions from the Philadelphia Inquirer that was provided to the Post. The archbishop serving at the time, Charles Chaput, immediately suspended Drotar after learning of the allegations, said Haas, the archdiocese spokesman. Many of the church’s leaders at the time are now serving elsewhere, Haas said, including Chaput, who has been archbishop of Philadelphia since 2011. Drotar appeared before the Conduct Response Team, attended counseling and completed a psychological assessment “to determine if this is deep-seated behavior and likely to continue, or a human mistake,” Haas said. The archdiocese then reinstated Drotar and posted him to Notre Dame. When Szutenbach learned that Drotar had been assigned to a parish, he reached out to the archdiocese. He was never asked to appear before the response team or provide any information about the abuse, he said. After speaking with Chaput directly, Szutenbach on Nov. 2, 2007, appeared before the response team to share his experience. After hearing from Szutenbach, the team immediately recommended that Drotar be removed from his work as a priest, which the archbishop implemented, Haas said. Szutenbach returned to his life in Florida, satisfied that he had done the right thing and he had been heard. But he continued to occasionally search Drotar’s name and found the man still calling himself a priest online. As news about Cardinal Theodore McCarrick’s abuse of young priests and seminarians became public in August, Szutenbach reached out to the archdiocese to see if Drotar had been laicized, or officially removed from the priesthood by order of the Vatican. Haas said he wasn’t sure whether the Denver archdiocese ever pursued that process, which would take years. The diocese ordered that Drotar never dress as a priest, practice the church’s sacraments or present himself publicly as an ordained leader. In order to work in a new diocese, Drotar would need a letter from the Denver Archdiocese stating that he is a priest in good standing, Haas said. “For all intents and purposes, he’s been fired from his ability to function as a priest,” Haas said. Haas said he was aware of Drotar calling himself a priest on the internet, including several comments on online obituaries calling himself “father.” But Haas said there’s little the archdiocese can do about those posts. Szutenbach was surprised and angered to learn that the archdiocese had never pursued the defrocking process. Haas said he was not aware of any other allegations of seminarians being abused by faculty at St. John Vianney seminary. He noted that the diocese has had a zero tolerance policy regarding criminal sexual abuse of children by priests since 1991, but that those rules only apply to child victims and criminal accusations. “(Szutenbach’s allegations) were never reported to the archdiocese as a criminal matter,” Haas said. But the archdiocese’s defense does not impress Szutenbach. “It’s only non-criminal if you don’t think of it as an assault and because I didn’t press charges,” Szutenbach said. “I asked (Drotar) not to do it every time.” Contact: eschmelzer@denverpost.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.