|

Northern New Mexico man breaks silence on priest abuse he suffered as teen seminaria

By Cody Hooks

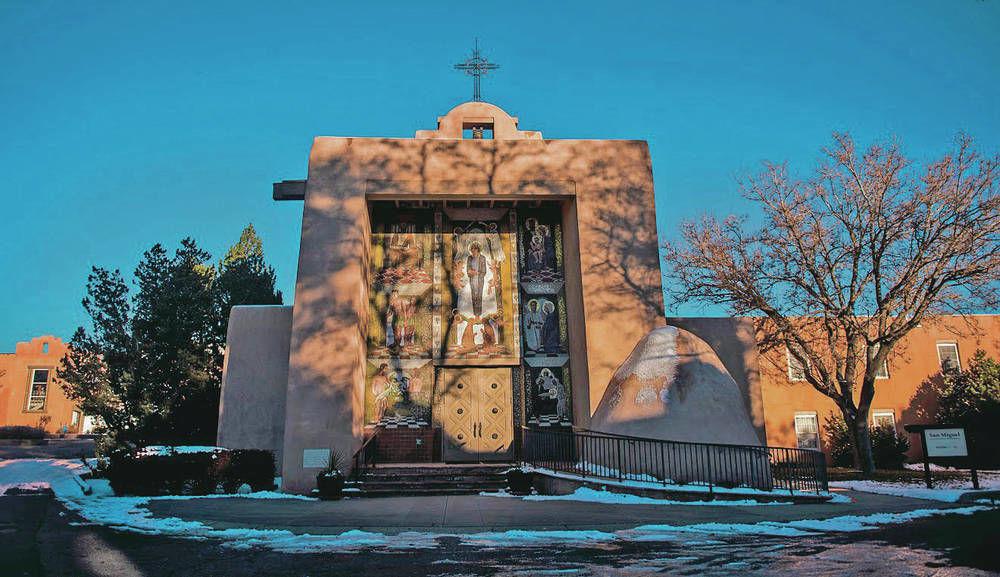

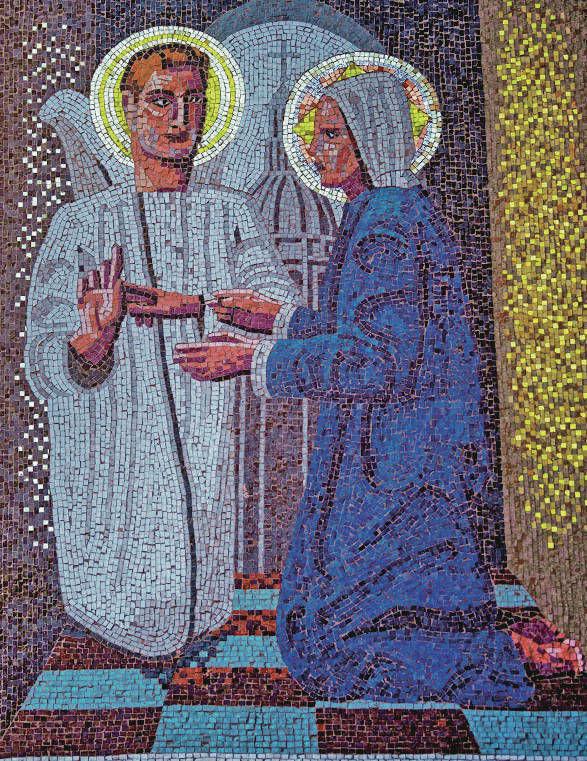

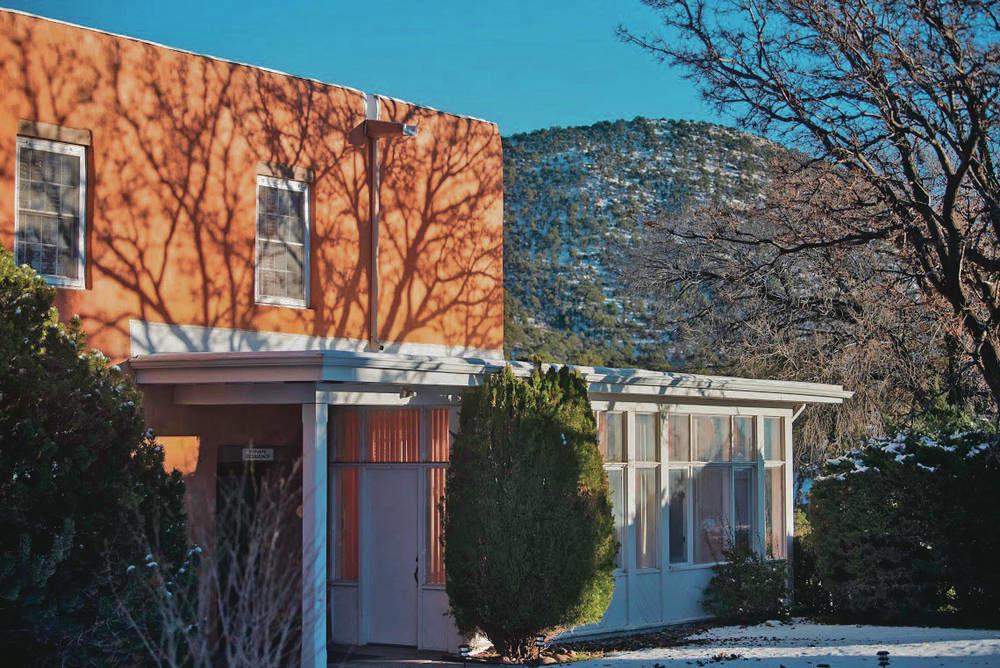

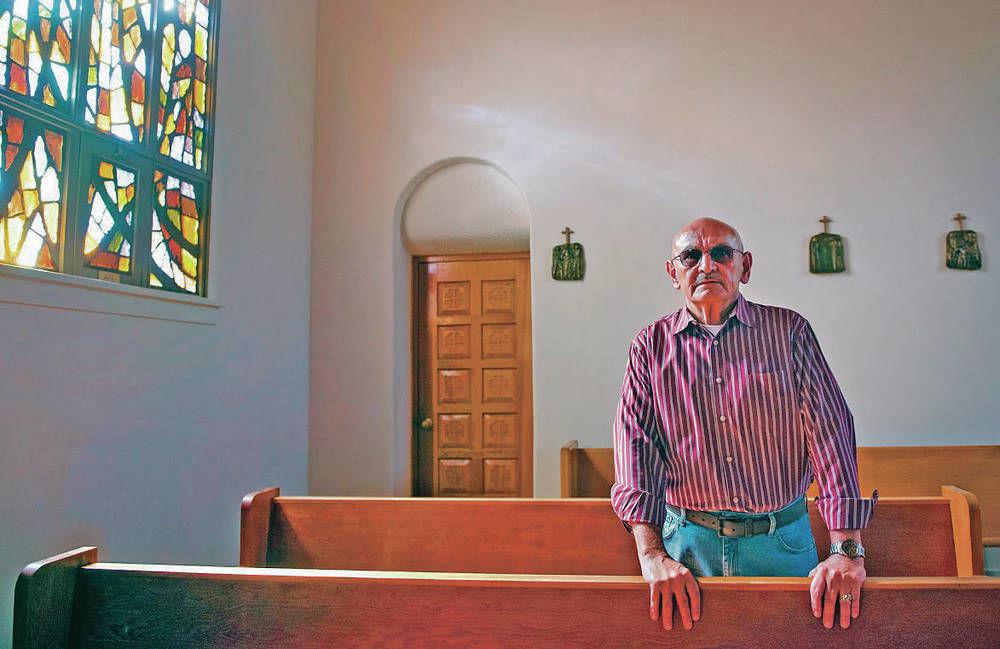

Donald Naranjo had gone back to the old seminary campus in Santa Fe only once since he was a teenager, but he still knew where to turn: Make a right at the midcentury house with a double garage, go east about a mile, turn left. Naranjo, now 70, was a sophomore in high school when he convinced his parents to let him heed a calling. He started his studies to be a priest at the Immaculate Heart of Mary Seminary on the eastern edge of Santa Fe, a facility that now serves as a retreat. For a kid from the Española Valley, a heavily Catholic community, it was the kind of choice that makes a family proud. “If you wanted to seek a vocation in the church, it was wonderful,” Naranjo said. “You’d be right there next to God.” His mother, sitting behind the wheel of the family’s Ford Falcon, dropped him off at the seminary in August 1963, when he was 15. The abuse started soon after, Naranjo said. Known as John Doe No. 60 in a civil lawsuit against the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, Naranjo is one of scores of people who have sued the archdiocese, claiming abuse by a priest, and one of thousands nationwide. Like many other priests from around the country, the man Naranjo accused of abuse, Earl Bierman, came to New Mexico for treatment at a Jemez Springs facility that became a dumping ground for sexual abusers. It was run by the Servants of the Paraclete, a religious order in New Mexico with close ties to both the Catholic Church’s hierarchy and local parishes. At least two lawsuits allege Bierman abused young men at the Santa Fe seminary: one filed in 1995 and Naranjo’s in 2016. Bierman died in prison in 2005 as he was serving out a 20-year sentence for pleading guilty to sexually abusing boys in three Kentucky counties while he was a priest there. Naranjo, who has settled his case with the archdiocese, is one of the few claimants of Catholic clergy abuse to share their stories publicly. He told the Taos News that he hopes his story will help prevent further abuse by clergy and will prompt other victims who have remained silent about abuse to begin a path of healing. “My fear is people feel so guilty and responsible they don’t seek help,” he said. Naranjo never finished his training to be a priest, he said. He dropped out after a year and a half, moved back home and quit going to church. He did a stint in the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam War, got married and divorced, drank and got sober, and married again. He had decades of sleepless nights. Naranjo’s time at the Santa Fe seminary became a blank stretch in his memory. Images of repeated sexual abuse there flooded back into his mind four years ago, he said, when he was receiving treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder he had assumed was caused by his time in combat. Now the memories wrap around his body like muscles and tendons. When Naranjo walked around the seminary campus earlier this year, nobody was around. The campus was hushed. “It’s amazing,” he said. “The beauty of this place. And then all that ugly crap that happened.” Confession Seminary life for high school boys was a lot like school anywhere else, with classes, homework and PE. Naranjo recalled playing tennis on courts that were torn up to make way for a lawn and running with the class up a piñon-covered hill in the mountains. Sometimes, he and his friends met there to smoke a cigarette — the last bastion of teenage rebellion. The seminarians talked theology, attended Mass and went to confession. For Naranjo, those most intimate moments of spilling his sins before a priest happened in a second-floor apartment. Every week or two, he went to see Bierman. “He would have me kneel next to him, so I could go through my confession,” Naranjo said. “That moved into the fondling, the oral sex and the sodomy and … that stuff.” Naranjo remembers an “unwritten rule of silence” during his semesters at the seminary. “You don’t share this with anybody,” he said. “And if you do, who’s going to believe you?” There was no one to tell, he said. “The church was everything in rural communities, and you never spoke bad of your priest,” he said. “… I didn’t want to cause any discord, so I buried this and shouldered it.” Survival After he graduated from high school in Española, Naranjo spent about four years in the Navy as a medic. He was deployed to Vietnam and worked in a small clinic outside Da Nang. Though he wasn’t fighting, he wasn’t insulated from the worst of war: bodies in pieces; a boy, the same age as his kid brother, with his skull blown off; Naranjo’s own arm elbow-deep in a man’s chest, trying to restart his heart. After his service, Naranjo came back, moved to Albuquerque and started a family. He and his wife had two boys. They moved to Michigan for a few years, where he earned a doctorate in education. Despite Naranjo’s successes, the two decades after seminary were marked by the scars of his traumas. From the time he was a senior high school, Naranjo drank. He coped that way for years. Finally, in 1983, after an embarrassing incident at an event held by his wife’s employer, he decided to get sober. The family moved back to New Mexico, where Naranjo ran a behavioral health organization. He traded two or three cocktails before bed for a workaholic’s schedule. He struggled with sleepless nights. Naranjo’s first marriage ended in 2003. A couple of years later, he married his second wife, Simona. Outside of their marriage, Naranjo was mostly “closed up, not letting anybody in,” Simona said. “He told me about what he did at the time he was out in Vietnam,” she added. Eventually, she began pushing him to go to the Veterans Affairs Medical Center to seek treatment. He complied, and in 2015, he was diagnosed with PTSD. In a therapist’s office, Naranjo would relive his experiences from the war. “I remembered it all, everything,” he said. But he couldn’t recall much about his year and a half at the seminary. The blank unsettled him. After months of talking with his VA therapist, Naranjo decided to take his treatment a step further. He went to a professional trained in EMDR — eye movement desensitization and reprocessing — a type of psychotherapy proven effective at treating trauma. Naranjo finally started to remember: That priest, Bierman. Being called into his apartment. The room. The chair in the middle of the room. The starched, black cassock that hung down to the priest’s ankles. His socks. The abuse. Naranjo recalled the priest explaining why it had to happen: “I was going to have to experience certain things, so I could deal with my parishioners.” After the breakthrough, Simona watched as depression and anger crept over her husband. “I knew it hurt,” she said. “You could see it in him.” ‘My cross to bear’ Bierman had an extensive profile as an accused and convicted abuser. A 1995 lawsuit stemming from one man’s experience at the Santa Fe seminary alleged Bierman had molested numerous children there. A news report that same year documenting a civil trial in Kentucky, where Bierman served for three decades, said the Diocese of Covington had received as many as 73 abuse complaints against him. Bierman had been dead for a decade, about as long as the seminary had been shuttered, when Naranjo’s abuse came to light, he said, but he still wanted justice. He went to see the Law Offices of Brad D. Hall, an Albuquerque attorney who has mounted dozens of sexual abuse lawsuits against the Archdiocese of Santa Fe since 2012. It wasn’t money Naranjo wanted out of the process, but transparency. “I wanted the archdiocese to go through their records, ID my classmates and send a letter telling them the abuse was happening and there’s help available,” he said. The response was a firm “no,” he added. “They told me they could set up a meeting with the archbishop, and he could shake your hand and say he’s sorry,” Naranjo said. “Well, after everything that had happened, I wasn’t terribly impressed with the idea.” Naranjo recalled the day when he and his lawyer would hammer out a settlement with the archdiocese. From morning to evening, he said, lawyers from each side would go back and forth with offers and counteroffers. “They said yes; they said no. We said no; they said yes,” Simona said. “… It wasn’t really talking about what happened and what they actually did.” Naranjo was ready to pass on a settlement and get his day in court. Simona didn’t like the idea: “I knew what this was doing to him, with the crying, the hurt, the depression.” Ultimately, Naranjo backed off a trial for a different reason. “I didn’t mind agreeing to go to court, but they said, ‘Fine, we’ll have to depose all your family members,’ ” he said. His wife — his rock through this whole ordeal — would be questioned, and so would his brother and sister, his children and maybe other family. “That’s not going to happen,” Naranjo told them. “I’m not subjecting my family to it. I’m not bringing them in here. This is my cross to bear.” “So we settled it,” he said. He couldn’t disclose how much money was involved in the settlement because of an agreement with the archdiocese. But he believes the archdiocese — and the Catholic Church at large — haven’t been held accountable. He’s angry about that. “I don’t get upset about Vietnam because I asked to go,” he said. “I volunteered to join, to be a corpsman to take care of people who were hurt. It still haunts me, but that was my decision. “What happened at the seminary,” he said, “was not my decision.” Still, Naranjo has hope for survivors like himself. He pointed to the case of Arthur Perrault, a former priest accused of sexually assaulting minors. Perrault recently was extradited to Albuquerque from Morocco to face federal charges of molesting a child while serving as a chaplain at Kirtland Air Force Base. Perrault had gone into hiding in the 1990s after allegations of abuse began to surface. At least three dozen people have accused him. But now he is in jail and facing trial. That, Naranjo said, “is a start.” In 2017, Naranjo worked with state Sen. Mary Kay Papen, a Las Cruces Democrat, to pass legislation that modifies the civil statute of limitations related to sexual abuse crimes against minors. Under the new law, even someone Naranjo’s age has three years to file civil actions after they first document abuse with a medical or behavioral health professional. Naranjo also hopes to reach out to his classmates from the seminary, old men who were once vulnerable boys. And he wants to reach out to parents, encouraging them to have the conversations with their kids that his parents never had with him. He acknowledges it’s a different era. Young people today “question a lot, which is good,” he said. “You should ask and not give blind obedience to anyone.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.