|

The Class of `74: Where are they now?

By Pat Navin

Medium

December 4, 2018

https://bit.ly/2PhbooQ

|

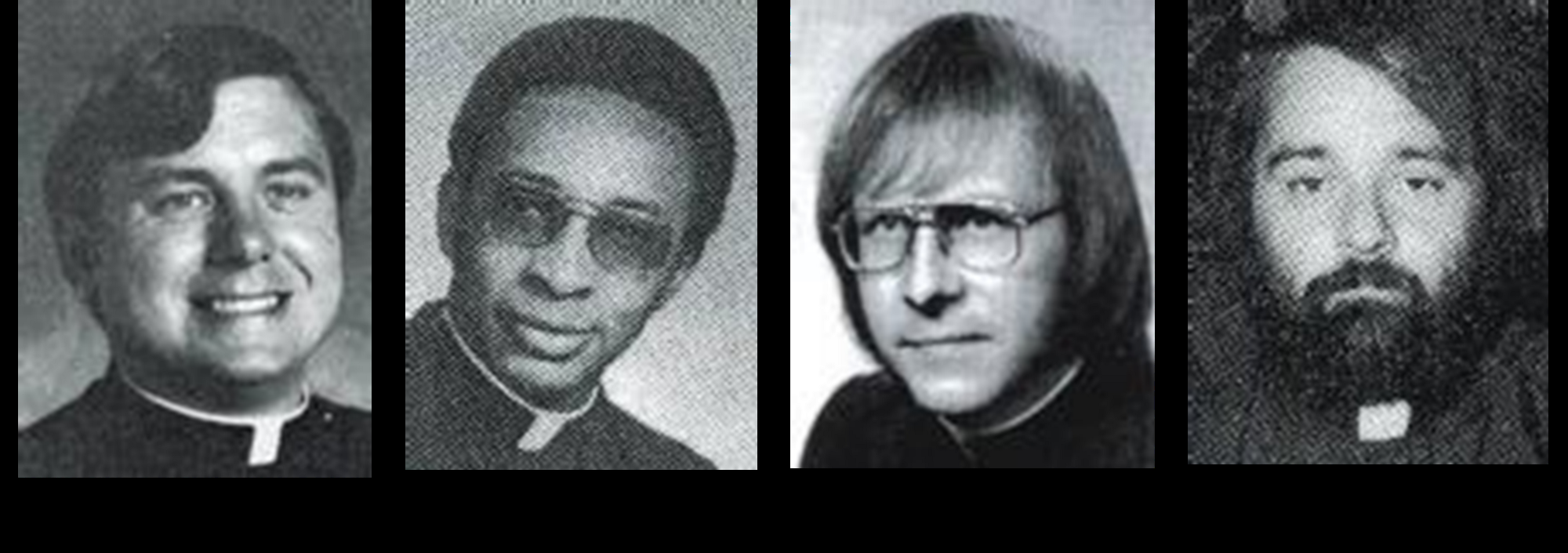

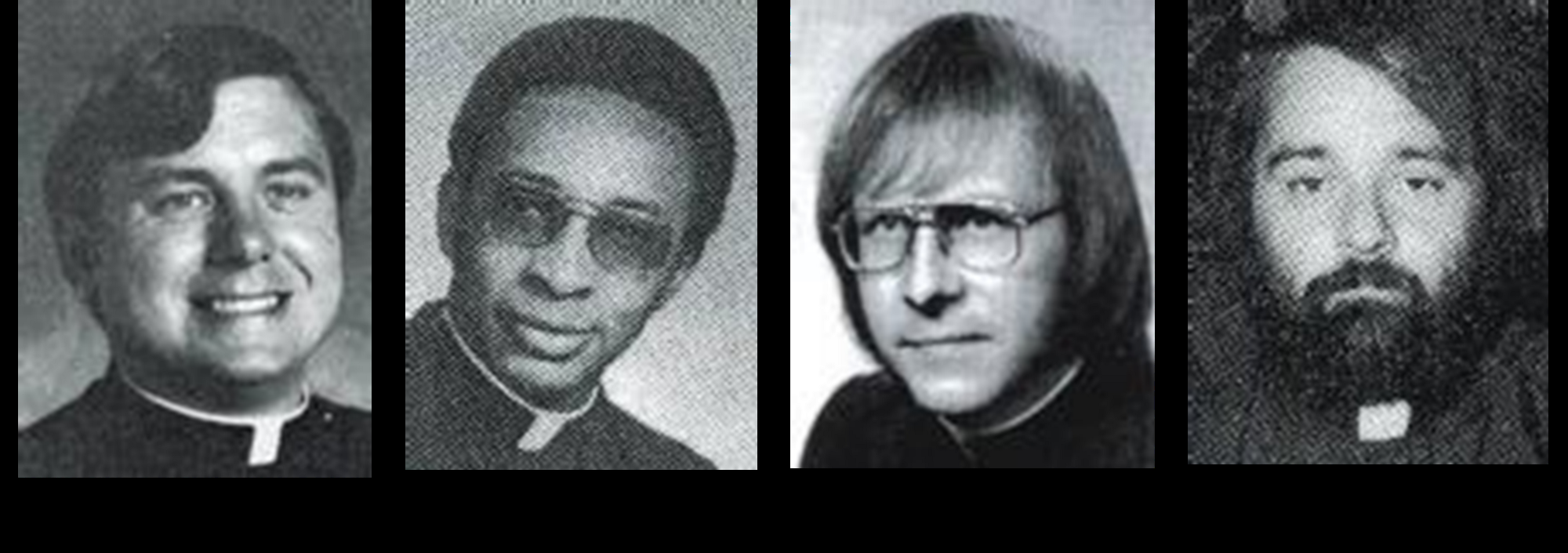

| From left: Richard Barry “Doc” Bartz, John Walter Calicott, Robert D. Craig, James Craig Hagan |

|

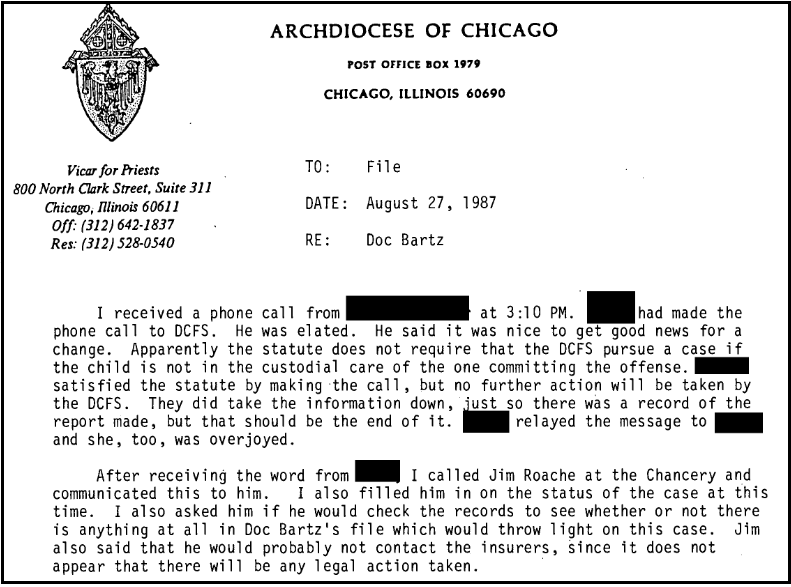

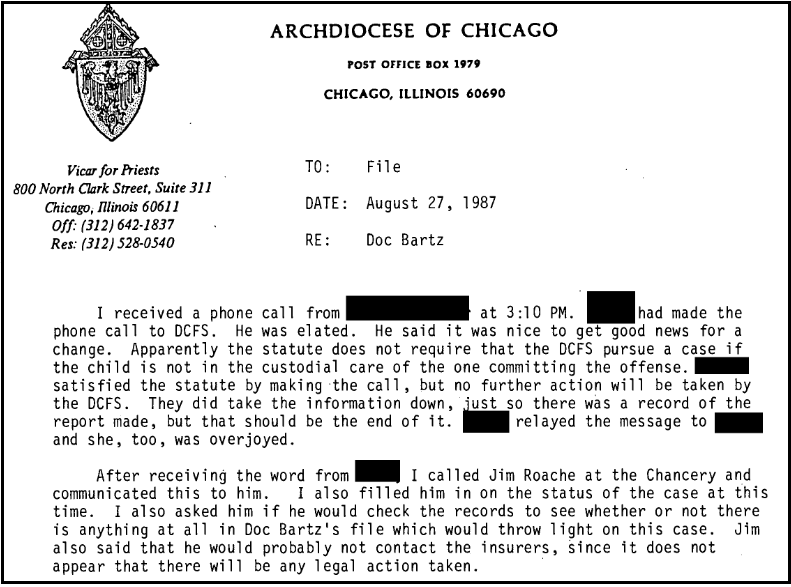

| “Elated.” “Good news.” “The end of it.” “Overjoyed.” That’s how Vicar for Priests, Bishop Raymond Goedert, described reaction to the news that a priest’s criminal sexual abuse of a minor wouldn’t be reported to law enforcement authorities. |

|

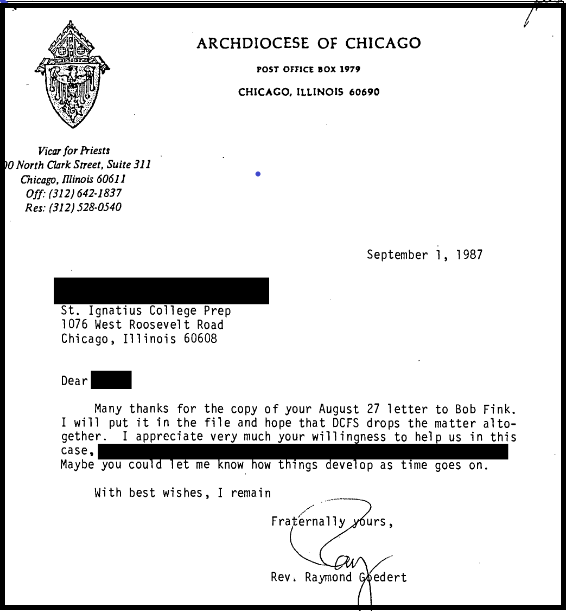

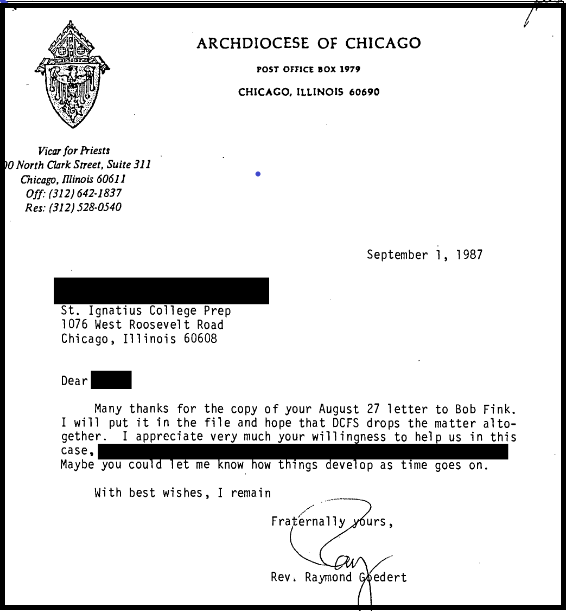

| “Willingness to help us in this case.” Goedert’s note suggests he and the Archdiocese were grateful for the principal’s assistance in keeping Bartz’s sexual abuse case from being forwarded to police or prosecutors. |

|

| Calicott’s first credible abuse allegations were reported to the Archdiocese in 1994. The abuse occurred during his first parish assignment at St. Ailbe’s in 1975. |

|

| “In 1988 I told the Archdiocese they had better watch him and if anything else happened I would go public.” |

|

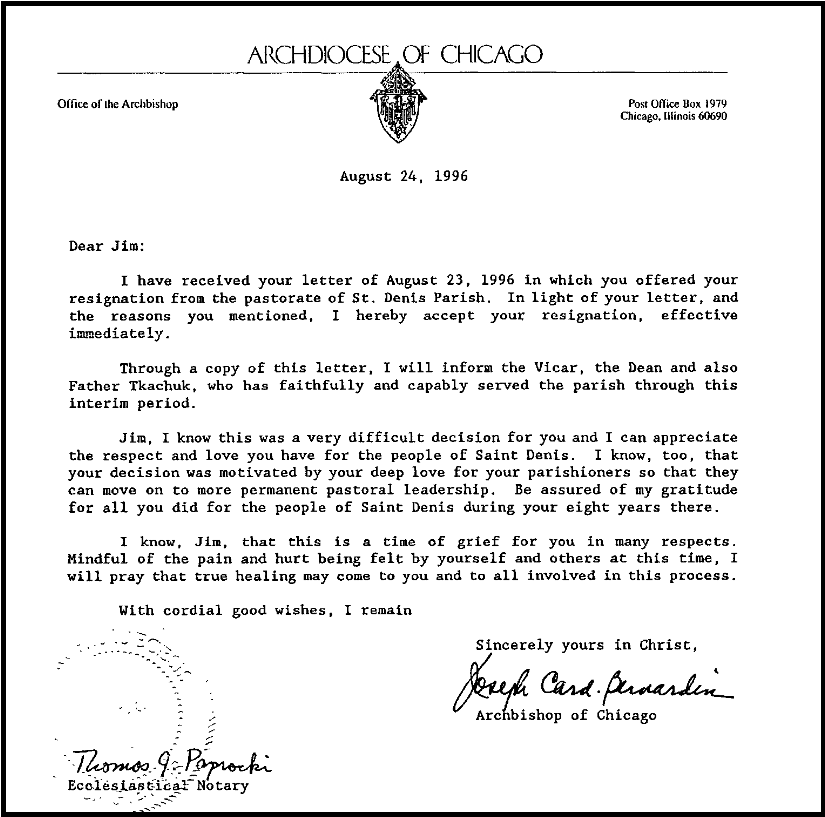

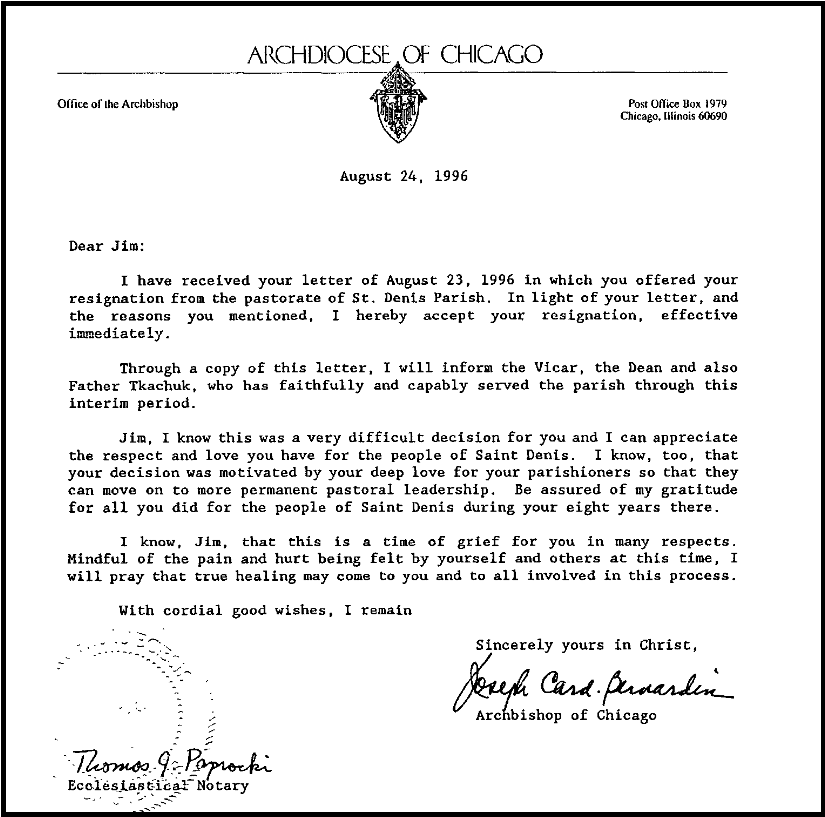

| “Be assured of my gratitude for all you did…” |

May 8, 1974 was an unseasonably cold, gusty and stormy day in Chicago. But inside the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception at St. Mary of the Lake Seminary in northwest suburban Mundelein, the assembled faithful beamed with warmth, pride and a sense of peace. Their sons, grandsons, brothers, nephews, cousins and friends were about to be ordained into the priesthood by John Patrick Cardinal Cody, prelate of the Archdiocese of Chicago, in a ceremony filled with all the pomp and circumstance the institution could muster.

The newly-ordained priests had already received notices of their first parish assignments and they were anxious to make their marks: baptizing babies, ministering to the sick and dying, celebrating the Eucharist, listening to confessions, presiding over weddings and funerals, and, apparently, for at least four of the new priests, sexually abusing boys (and, for one of them, girls as well).

Out of the nearly 100 Diocesan priests in the Chicago Archdiocese who have been credibly accused of abuse according to Bishop-Accountability.org (the Archdiocese puts the number at 65), the class of `74 carries the distinction of having the largest number of accused priests of any single ordination class. Three of the priests — Richard Barry “Doc Bartz, John Walter Calicott and Robert D. Craig — hit the ground running, with credible abuse allegations from their very first parish assignments. The fourth, James Craig Hagan, had not collected any substantiated reports from his first assignment, but made up for lost time at his second parish. Hagan was also the only one of the four who abused both boys and girls.

Their highly edited and redacted files, which became available when the Archdiocese was finally forced to make them public in 2014, include sordid details of abuse and a litany of excuses, cover-ups, reassignments from parish to parish to parish to positions as hospital chaplains or seminary officials. They contain notes from Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, Cody’s successor, and other Archdiocese religious administrators encouraging the abusers’ efforts at self-improvement and offering prayers of support. The files also contain mundane housekeeping notes on how the documented abusers would continue to receive their salaries, status reports on payments for their health insurance, auto insurance and other expenses, and options for future living arrangements.

What is not found in their files is any indication that corroborated claims were, as a matter of policy, forwarded to law enforcement authorities without threat of a subpoena.

What is also not found in the files is even a modicum of understanding or empathy for those who were abused.

In August 1987, Fr. Richard “Doc” Bartz was accused of molesting a 17-year-old male high school student (identified in documents as Victim ID) who attended Chicago’s St. Ignatius College Prep. The allegation was reported by a “relative” of the student to the principal of St. Ignatius who in turn notified the Archdiocese and the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS). Subsequent reports in Bartz’s file indicate that Bartz may have attempted to molest at least one additional boy (identified as Victim IE) the same evening as the original allegation. The documents include mention of “oral sex,” though further details of the incident(s) are not included or have been redacted.

Illinois law at the time only required a DCFS follow-up with legal authorities if an abuse report was made directly to DCFS by “a family member, guardian or someone considered a paramor [sic] of a parent or guardian,” according to a letter in Bartz’s file from the St. Ignatius principal. Since the principal was the person making the report to DCFS, the rules for passing the report on to legal authorities did not apply.

In short, the charges against Bartz would go no further. This was cause for rejoicing, according to a note-to-file by then Vicar for Priests, Auxiliary Bishop Raymond Goedert, the Archdiocese official charged with handling abuse cases.

Bishop Goedert even sent a thank you letter to the principal of St. Ignatius with the “hope that DCFS drops the matter altogether.”

Bartz was removed from St. Eulalia parish in Maywood in 1991 and became a hospital chaplain. A further allegation against Bartz, stemming from his time at Ascension parish in Oak Park, his first assignment, was brought to the Archdiocese in 1992.

Bartz resigned from the priesthood in June 2002, though he wasn’t laicized until September 2015. He was never charged with a crime.

[Note: I reported my own experience with Bartz to the Archdiocese in 1992, and, ultimately, brought my information to reporter Todd Lighty at the Chicago Tribune in 2002, shortly before Bartz resigned. More on that below.]

Credible abuse allegations against Fr. John Calicott posed a challenge for the Archdiocese.

Two credible accusers came forward in 1994 claiming that Calicott had sexually abused them on multiple occasions beginning in 1975 during his first parish assignment at St. Ailbe on Chicago’s south side. By 1994, Calicott had become a prominent pastor at Holy Angels parish, also on the south side. Cardinal Bernardin was faced with a deluge of petitions and letters from Calicott’s then-current parishioners and other neighborhood religious leaders requesting that Calicott be kept on as pastor at Holy Angels.

After the Archdiocese Fitness Review Board initially placed Calicott on “administrative leave” at the Mundelein seminary campus — a frequent home for priests with credible abuse allegations — the board reinstated him to his position at Holy Angels in October 1995 “with restrictions and monitoring.”

How gut-wrenching had it been for one of Calicott’s accusers to come forward in 1994 and finally unburden himself about his repeated abuse at the hands of Calicott in the mid-`70s?

“The most difficult part of it was remembering it and letting it out. After I went to the Archdiocese and told them my story, I literally cried for three days. No sleep. I was actually afraid to sit down. I was so overwhelmed by the emotion, I was afraid if I sat down, I would never stand up again.”

Shockingly, amid further reports of Calicott violating terms of his “restrictions and monitoring” agreement in 1999, the Review Board once again allowed Calicott to continue as pastor at Holy Angels.

In 2002, Francis Cardinal George ordered Calicott to leave Holy Angels and move, once again, to a residential hall on the seminary campus. Calicott refused to move to the seminary, though he did leave the parish rectory. He also refused to resign from the priesthood, and for the next four years, he continued to be involved with the parish, including, remarkably, teaching sex education at Holy Angels in 2004. He also continued working with a nearby Baptist church’s Boy Scout troop, including accompanying the troop on trips.

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith found Calicott guilty of sexually abusing minors in February 2006, effectively removing him from the priesthood. He appealed and lost. Calicott was laicized in 2009. He was never charged with a crime.

Robert Craig was a known threat even before he was ordained. The minutes of a meeting of the Diocesan Clergy Personnel Board from February 19, 1974 included the following note about Craig:

Robert Craig is a hard worker; must have someone working with him; will need a pastor who can tolerate non-clerical dress; very smart. He wants to be in the City where he can continue his work at the Audy Home. He would tend to move free and independent. Tom’s advice: be concerned.

The “Tom” in this case was Father Thomas Murphy, then rector at St. Mary of the Lake Seminary. The Audy Home was Chicago’s facility for juvenile offenders. What did seminary administrators know about Robert Craig, and why did they allow him to be sent to his first parish where he almost immediately began molesting and abusing boys?

From 1974 through 1990, Craig spent time as an Associate Pastor in four parishes and was ultimately accused of sexual abuse, molestation, attempted rape and rape, including incidents during his first parish assignment at St. Aloysius on the city’s west side.

In 1990, Craig provided Vicar for Priests, Bishop Raymond Goedert, with a list of “more than five” boys he had abused. The Archdiocese kept the list secret.

Craig resigned from the priesthood in 1993 and was laicized in 2009. He was never charged with a crime.

James Craig Hagan did not have any abuse cases in his Archdiocese file from his first assignment at St. Catherine parish in Oak Park. But upon arrival at St. Richard’s on Chicago’s south side in 1981, Hagan apparently made up for lost time.

In 1996, four men accused Hagan of molesting them when they were between the ages of 12 and 16 during the five years he was at St. Richard. Another man came forward in 2003 and accused Hagan of fondling him and performing oral sex on him in 1982 when the man was 15.

Hagan was moved again in 1986 to St. Gertrude parish in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhood where he remained for two years. While there, Hagan began molesting girls as well as boys. Several mothers called the parish office to complain at the time, as outlined in this letter from a concerned parent to the Archdiocese dated April 25, 1996:

The next day, April 26, 1996, the Archdiocese crafted a set of talking points marked “For internal use/Do not distribute” seeking to provide cover and a timeline about what they knew and when they knew it regarding Hagan’s many abuses. It includes this Q and A:

Q: Have there ever been prior allegations involving Father Hagan?

A: Yes. One allegation in 1988 was determined to be unfounded by DCFS and the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office.

As referenced in the mother’s letter, Hagan was promoted to pastor at St. Denis on the south side in 1988 where he remained until resigning in August 1996 after allegations against him had become public.

Cardinal Bernardin sent a heartfelt response to Hagan’s letter of resignation:

But what does the Cardinal tell someone who had been abused by Hagan?

“Move on.” Essentially, “Forget about it.” And analogizing being a victim of clergy abuse to being a cancer patient? This from a man who was considered one of leading progressive lights of the Catholic Church during this period.

Hagan resigned from the priesthood in April 1997 and was laicized in 2010. He was never charged with a crime.

“Put it behind you.” “We must forgive.”

Echoes of what I was told by Joseph Cardinal Bernardin in the summer and fall of 1992.

But let me start at the beginning…

I was raised Catholic and attended Ascension Church and School in west suburban Oak Park. It was a great community. My friends, my siblings’ friends and my parents’ friends were nearly all from families in the parish. That’s what growing up in a strong parish was like.

My parents weren’t particularly religious. We went to church every Sunday. My dad belonged to the Knights of Columbus and the Holy Name Society. The groups did good works in the parish, but they also served as fraternal drinking organizations. My mom helped out in the school and in the Altar and Rosary Society. We knew the priests, of course, but we weren’t one of the families that had priests over for dinner.

After graduating from Ascension School, I went to Oak Park and River Forest High School instead of Fenwick, the local all-boys Catholic high school. Many of the Ascension kids who moved on to the public high school, including me, would attend CCD (Confraternity of Christian Doctrine) religious classes once a week, typically on a Wednesday evening at someone’s home.

A group of us became friends with a young priest assigned to our parish. He had been ordained in 1970 and Ascension was his first assignment. He was funny, thoughtful and kind. We liked him. I remained friends with him well into adulthood. My wife got to know him. We shared meals and stories. Although I have lost touch with him in recent years, he figures prominently in the story I am about to tell. (I am not naming him here because there is no reason to drag his name into this.)

A new priest, Fr. Richard Barry “Doc” Bartz, joined our parish during the summer of 1974 between my junior and senior years of high school. I didn’t really like Fr. Bartz, but I couldn’t put my finger on the reason why. A group of us would occasionally do something with the two young priests — bowling, lunch, skiing. I never heard of anything untoward happening nor did I witness anything.

My friends and I all went off to college.

I was home for winter break during my freshman year. It was early January 1977. I was 18, turning 19 in March. Bartz called on a Monday evening and said, “We’re going skiing tomorrow morning, coming back Wednesday night. Do you want to go?” I love to ski and didn’t get many opportunities in pan-flat Champaign, Illinois, home of the University of Illinois. I said yes, figuring there were a group of us going.

Bartz shows up to my house the next morning. I run out with my bag and he pulls away from the curb, heading for the highway. I ask, “What about the other guys?” “They can’t make it,” he replies. That was a tell. I should have told him to turn around, but, frankly, I wanted to go skiing. (I found out later that he had never asked anyone else to go.)

We’re staying overnight at the resort. (I think it was Alpine Valley in Elkhorn, Wisconsin, but I’m not certain.) After dinner, we head to the room (two beds) we’re sharing. I fall asleep.

In the middle of the night, I am awakened by someone fiddling with my shorts. The zipper has been pulled down and the front of my shorts has been opened. I wake up, startled. “What the fuck...”

Bartz immediately jumps up from beside my bed and goes to the thermostat on the wall, pretending he’s adjusting the temperature. “It’s hot in here,” he says. He climbs back into his own bed as if nothing happened.

Now I’m lying in bed wondering what I should do. I am silent. My heart is racing a thousand miles a second. I’m thinking, “If I kill this guy, how do I get out of that one? A guy killing a priest in a resort hotel room?”

I grab one of my ski poles which are standing in the corner next to my bed and place it next to me on top of the covers, figuring if he comes near me again, I’ll ram the ski pole right through his gut. I’ll deal with the fallout.

I lie awake for the rest of the night, staring at the ceiling.

In the morning, Bartz pretends nothing happened. He suggests we get breakfast and go skiing. I tell him I want to go home. Now. He offers a mild protest. “Now,” I say.

The ride home is dead silent. I pretend I’m asleep. He drops me off.

I immediately tell my mother what happened. She’s shocked. She says, “You should have called us!” When my dad gets home that evening, I tell him. He says, “You should have called me! I would’ve come and picked you up!”

(I’m one of the lucky ones. My parents believed me. Immediately. Many abuse survivors are not so lucky.)

I tell my parents, “Well, I figured I could handle it. I was ready to ram him with a ski pole if he tried anything else.”

We discuss what to do next. Do we report it? To who? What would we say? We finally agree that my parents should tell all of their friends in the parish to keep their boys away from Bartz. And I would definitely tell all of my friends. (I know it may sound strange now, but in those days, these assaults were typically not reported to either the church or the authorities. The belief was that they would be swept under the rug, anyway.)

The following Sunday, I’m in church seated in a pew with friends. Bartz makes his way down the aisle to where we are seated. He is, again, acting as if nothing happened. He leans in to say hello to us, and I tell him in a low whisper, “Get the fuck away from me or I’ll crack you right here in church.” My friends know I’m serious. He slinks away.

I never spoke to Bartz again, though I did run into him twice in later years, once in passing on a sidewalk on Chicago Avenue near Rush Street where I glared at him and spit on his shoe, and once at a gas station where we both happened to be filling our tanks. I stared at him. He looked terrified and and quickly looked down, avoiding my gaze.

At some point during 1990, I told my priest friend what had happened with Bartz in 1976. He was not surprised. He informed me that Bartz had additional cases in his file at the Archdiocese.

In February 1992, Cardinal Bernardin announced, to much fanfare, that the Archdiocese of Chicago would appoint a commission to look into clergy sexual abuse.

Bernardin was viewed as being among the most progressive and liberal leaders in the U.S. Catholic Church at the time.

“The introduction of a review board with lay people on it will change things,” Cardinal Bernardin said in a telephone interview on Saturday. “Up until now we have been dealing with these problems on an in-house basis.”

I had absolutely no faith that the findings of this commission would amount to anything positive for those who had been abused. There was simply too much at stake for the Church. Nevertheless, in June 1992, I had lunch with my priest friend and he told me that the Archdiocese was making a serious effort to look into past abuses. My friend asked me to make an appointment to talk with the person assigned to look into the cases.

I was skeptical. “Is it another priest?”

“Yes,” he replied, “but the Cardinal is serious about looking into these cases. You should go talk to this guy.” He gave me the priest’s contact information.

A couple of days later, I called the number and made an appointment to meet the investigating priest. The Archdiocese had set him up in an office in a dingy third-floor walk-up at 800 N. Clark Street, kiddy-corner from Holy Name Cathedral, the Cardinal’s home church. It was a short walk from my office.

On July 8, 1992, I met with Fr. Patrick O’Malley, then Vicar for Priests, in a poorly-lit, dusty, sparsely-furnished office. Fr. O’Malley was pasty-white, late middle-aged, with thinning white hair. We shook hands, sat down facing one another and he told me a little bit about his mission. Cardinal Bernardin had tasked him with speaking to people who claimed to have been abused by priests, get their stories and then bring these accusations to the priests in question. He told me how painful these events have been for the priests involved. He also said the Archdiocese was offering free counseling to those who had been abused.

It all sounded like a tragically bad idea to me — a thought that was quickly confirmed when, after telling O’Malley my story, his first question was:

“Had Father Bartz been drinking?”

“What?”

As if to explain, he said, “Well, you know, sometimes after someone’s been drinking…”

I was incredulous. “What do you mean?”

“Sometimes people do things after they’ve been drinking that they— ”

I cut him off, my anger rising. “Look, Father, I like women. I like to have a few beers. Do you know what would happen to me if I tried to pull a woman’s pants down against her will while she was sleeping?”

Silence.

“I would go to jail. Do you know where Bartz would be if he were a Boy Scout leader who did what he did?”

Silence.

“He’d be in prison.”

I asked the priest if he had any credentials or any training in dealing with victims of sexual abuse.

“Are you a psychologist?”

“No.”

“Psychiatrist?”

“No.”

“Social worker?”

“No.”

“Do you have any training whatsoever in dealing with people who have been sexually abused?”

“No.”

End of interview. I was livid.

I told Father O’Malley that he was in way over his head. That, generally speaking, I was all right with my experience, but that many others were not all right, and that these experiences were likely the most traumatic events of their lives. I told him he was playing with fire. That people who had been abused had committed suicide or turned to alcohol or drugs or other self-destructive behavior to deal with their pain, and that his uninformed questioning could trigger events for which he was wholly unprepared and untrained and could put people at risk.

I concluded by telling him that the last thing someone who has been victimized by a priest wants to hear is how painful these events have been for the priest.

To illustrate just how tone-deaf the Vicar for Priests was about all of this, he sought to reassure me before I left by telling me that he would “confront Father Bartz with this information and let him know that he had to be alert to his problem and his tendencies.”

I went back to my office and called my priest friend and yelled at him for 20 minutes. To his credit, he listened patiently and when I was done venting, he said, “You should write all of this down and send it to the Cardinal.”

Which I did.

My three-page, single-spaced letter to the Cardinal dated July 11, 1992 detailed all that I thought was wrong with the process. I received a brief response from the Cardinal, dated July 15, promising a longer response once he returned from vacation. He included a copy of “The Cardinal’s Commission on Sexual Misconduct with Minors” report that had been published in June.

The Cardinal sent a more detailed response to my letter on August 18. He explained that Bartz had been removed from parish ministry and that he was “reassigned to a setting where he would not be in contact with young people.”

Where Bartz actually was remained a mystery.

[Note: When Bartz’s file was finally released by the Archdiocese in 2014, I found that the letter the Cardinal had sent me had been dictated by Father O’Malley (pp. 76–79 in Bartz’s file).]

I wrote a follow-up letter to the Cardinal on September 14, 1992 with a series of questions and comments on his Commission report, as well as specific questions about Bartz’s status. Cardinal Bernardin responded on October 22. In that letter, Bernardin wrote:

The pain of the victims is real and lasting. That is something I have come to appreciate more and more.

Maybe he did, and maybe he didn’t, as you will sadly see.

At the end of his letter, Bernardin suggested that we meet to discuss these matters. On November 25, 1992, I went to the Archdiocese offices on East Superior Street.

His office was what one would expect for a Cardinal of one of the largest dioceses in the country: dark wood, rich fabrics, warm light. We sat in beautifully upholstered chairs. He was an exceptionally soft-spoken man, a holy man in many regards. He had a bandage on his forehead, the result of walking into an unexpectedly open closet door in the middle of the night, he told me. We ended up talking for a little over an hour.

We discussed his new policy and what I found to be the most glaring omission in his report: that there was not a single mention of turning over all files on accused priests to relevant police departments and the state’s attorney’s office. He said that his new Review Board was the appropriate starting point for allegations of abuse.

I asked him where Bartz was now. I told him how I felt guilty for not reporting Bartz to the Church or to authorities in 1976 because I was certain Bartz had gone on to abuse others. (He did.) The Cardinal would only tell me that Bartz was not in parish ministry and that he was being monitored. I reminded the Cardinal that were he not a priest, Bartz would likely be in prison.

I asked the Cardinal why his report was limited to sexual misconduct with minors. I wasn’t, legally, a minor when Bartz attempted to molest me, but the impact and the criminal nature of Bartz’s actions were just as valid. He reiterated that his policy was a starting point and that protecting children was the number one priority.

I asked why priests with multiple abuse cases in their files, priests such as Bartz, were still being allowed to minister, given that page 47 of the Cardinal’s commission report states:

“If a priest is convicted of sexual abuse, has abused multiple victims, has committed multiple offenses, has abused a single victim over a long period of time, has become a public scandal, or is a poor risk for change, he should not be allowed to return to any kind of ministry.”

Hadn’t these priests, at the very least, forfeited the privilege of ministering in God’s name? And haven’t you ignored the policy set forth by your own commission?

And this is where the Cardinal transitioned into “forgiveness.”

He talked eloquently about forgiveness and the need to move on, just as he had in his response to the letter from the man who had been abused by James Hagan.

I reminded him that before forgiveness, there must be justice, and that without justice, there can be no forgiveness.

I walked out of the meeting hoping I had made an impact, that I had helped the Cardinal see these offenses through the eyes of those who had been assaulted, abused and molested.

When Bartz’s file was made public in 2014, I found I had made no impact at all.

The file reveals that almost exactly one year after our meeting, Bernardin was seeking to overrule the recommendations of his own Review Board, headed by Steven Sidlowski, and ease monitoring protocols on Bartz who was then working as a chaplain at Columbus Hospital in Chicago:

Final determination on Bartz’s status lingered. The Review Board sought clarification of Bernardin’s position in January 1994. The Cardinal finally responded in September 1994:

Fast forward to January 2002. The dam was bursting in Boston, thanks to the relentless work of the Spotlight investigative team at The Boston Globe. All across the country, survivors of priest sexual abuse were stepping forward with their horror stories. Bishops, Archbishops and Cardinals were under fire. Lawsuits were being filed. For the Church hierarchy, there was nowhere to hide.

All of it made me physically sick. It brought the whole sordid experience back, from the incident itself, to the unsatisfying and, at times, infuriating interactions with O’Malley and Bernardin.

My priest friend called me in April and said, “This time, they’re really looking into it. A friend of mine is running it.”

“Is he a priest?”

“Yes.”

“You must think I’m an idiot.”

“Please. Just give him a call.”

“Okay, I’ll call him. For you. But this is not a route I think I’m going to take.”

I hung up the phone. I sat at my desk with my head in my hands. There was simply no way I would subject myself to dealing with the Church again.

I called the priest in charge of this latest investigation. I asked him a list of questions, including where Bartz was now. He wouldn’t answer. I told him I was going to do this my way, and it didn’t involve the Church. He asked me what I was going to do. “I’m going to the Tribune,” I told him. He stammered and muttered and slammed the phone down.

The Chicago Tribune had been producing its own pieces on the Chicago Archdiocese that mirrored what was happening in Boston. I sent an email to a reporter at the Tribune who had been working the story, Todd Lighty. I told Todd my story and that I had correspondence with the late Cardinal Bernardin and notes from my meeting with the Cardinal. Todd responded quickly, asked me where my office was and when he could come talk to me.

Todd walked through the door later that afternoon. I told him my story, handed him my letters and the letters from the Cardinal, my original notes on the Cardinal’s commission report and other notes I had made in 1992. I added that there was one enduring mystery: Where was Bartz now?

I had tracked Bartz online to Columbus Hospital, but Columbus closed in September 2001 and now Bartz was nowhere to be found. Todd told me that it had been hard to locate a number of the accused priests as the Archdiocese wasn’t very forthcoming. We agreed to stay in touch.

Todd called a few days later and asked if I would like to add a quote to the story he was preparing about Bartz and two other priests. “That would be great,” I said, “but let me think about it. I’ll write something and email it to you.” He asked if I wanted my quote to be anonymous or if I wanted to use my name. “Use my name,” I said.

Before he hung up, he added, “Oh, I found Bartz. He’s a chaplain at Ravenswood Hospital.”

Ravenswood was owned at the time by Advocate Health Care, a large, regional health care organization. (Unknown to me at the time, Bartz was actually serving as chaplain for a separate entity within the hospital, the Chicago Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroresearch.) I looked up the email addresses of Advocate’s CEO and its head of communications and sent them a short note explaining that they had a chaplain on staff at Ravenswood with at last three documented cases of sexual abuse in his files at the Archdiocese.

Todd called me the next day and said that Bartz was gone from Ravenswood.

The story broke in the Tribune on June 20, 2002 under the headline:

The story included this:

One of Bartz’s alleged victims, Pat Navin, said the archdiocese should have acted a decade ago when he first reported his complaint.

“He should have been removed then,” said Navin, who was 18 when Bartz allegedly abused him in 1976 during a Wisconsin ski trip. “He had another allegation involving a minor. He had multiple cases in his file. Hadn’t he at least forfeited his privileges to administer the sacraments?”

Four days later on June 24, Todd Lighty and Monica Davey bylined this piece in the Tribune:

Bartz and seven other priests, including his 1974 classmate, John Calicott, had been removed from ministry.

Bartz resigned from the priesthood.

When attorney Jeff Anderson finally succeeded in forcing the Archdiocese to release the files of Bartz and 35 other priests on November 6, 2014, Todd Lighty sent me a quick note alerting me to the release.

Todd and two other reporters filed a piece that day documenting victims’ responses to what was in the files. He asked if I would like to offer a comment for the piece after reading through Bartz’s stomach-churning file and I did:

After the archdiocese made the documents public Thursday morning, Pat Navin pored over the 362 pages in the file of Richard Bartz. Navin was 18 when Bartz allegedly abused him in 1976 during a Wisconsin ski trip. At the time, Bartz was associate pastor at Ascension Catholic Church in Oak Park.

Bartz was removed from public ministry and resigned as a priest in 2002. He could not be reached for comment.

“What is astounding about the file, in its entirety, is the amount of concern for the priest and the lack of concern for the victims,” said Navin, 57. “Not surprising, really, but a sad commentary on the priorities of the church hierarchy. … Reading this file was sickening. I feel physically ill.

“I never wanted to sue these people. … But now I’m regretting my decision not to sue them. The only thing they seem to have understood from the very beginning is losing money.”

None of this will come as a surprise to anyone who has followed the story of clergy sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church. Concern for the priest — and for the institution of the Church — were always paramount. Concern for those who were abused was a distant third. In most instances, survivors rated nary a mention in these files, save for the sanitized and summarized descriptions of abuse and assault, or in the plaudits to those who kept these criminal acts from authorities.

These four members of the Class of `74 have never faced criminal charges for their actions. The Archdiocese succeeded in hiding and stalling their cases long enough that the statute of limitations expired.

Where are they now? All four are still living in the Chicago area at last check, two in the western suburbs, one in a south suburb and one in a northern suburb. They’re not required to report as sex offenders. They’re free to travel where they want, when they want to do what they want. The Church has washed its hands of them. No one is monitoring them.

If it’s true that “time heals all wounds,” I would say that I am healed. I was healed long ago. But that doesn’t mean I forgive Bartz, and, I suspect, many survivors of clergy abuse are also unable to forgive.

Forgiveness follows justice. For those abused by four members of the Class of `74, there has been no justice.

|