|

In major shift, lay Catholics are organizing to push bishops on reform

By Michelle Boorstein

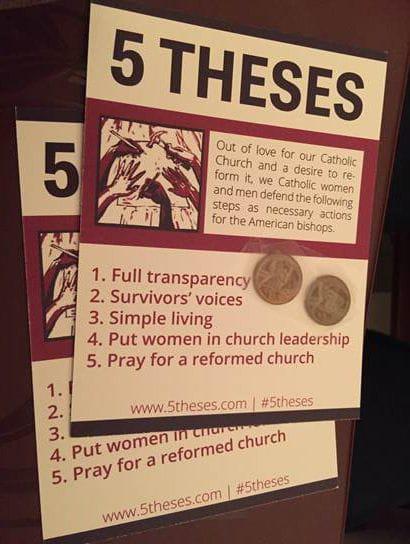

Five hundred years ago, Martin Luther of Wittenberg circulated his 95 theses, critiquing the Catholic Church and launching the Protestant Reformation. Liz McCloskey of Falls Church has five. Fed up with the way Catholic bishops have handled clergy sexual abuse of children, the 54-year-old academic’s group from Holy Trinity parish in the District has joined recently with groups from parishes in places such as Seattle and New York City on a project. They are affixing fliers with five demands to the doors of cathedrals and parish churches — meant to conjure a famous (if unconfirmed) tale about Luther nailing his demands to a German church door, an image that has come to embody grass-roots folks rising up for religious reform. Among the details on the list of five: Stop qualifying their actions or lack thereof and just cooperate fully with civil prosecutors who are investigating abuse in the church. Stop wearing fancy royalty-like garb and dress and live simply. Give space in every edition of every church newspaper to abuse survivors. The groups pushing for changes are among a small but growing number of U.S. Catholics who are organizing for internal reform — action that not long ago would have been an unheard-of challenge to church authority. In some cases, lay Catholics are making demands in cooperation with priests. “We’re in disruptive times, right? So many institutions have failed, in a way that people inside feel: ‘Hey, we’ve given institutional power to leaders for too long and they’ve failed us,’ ” said Keith Norman, a 52-year-old media executive who is part of a group at his Vienna, Va., parish that wrote its own petition of demands to the U.S. bishops. This has been a year of bitter discontent among American Catholics, with several high-level clerics leaving office because of alleged abuse or mishandling of abuse. While polls show thousands of Catholics have left the church in part because of anger over the handling of abuse allelgations, millions remain active in parish life. They tend to be those who — until 2018 — believed any abuse-related failings were sufficiently public and that reparations had been made. But in a CBS poll earlier this fall, a quarter of U.S. Catholics said that as a result of recent reports of priest sexual abuse, they have personally questioned whether to stay in the church. The recent revelations have led some across the ideological spectrum to say they are not satisfied leaving reform in the hands of the bishops and diocesan lawyers. “Catholics are newly awakened to power relationships. . . . The laity are for the first time feeling their own powerlessness,” said Kathleen Sprows Cummings, a historian at the University of Notre Dame who runs the school’s center for the study of American Catholicism. While a wave of Catholics began organizing for internal reform in the early 2000s, Cummings said, even then the push only went so far. The call then was more for laypeople to be involved than for them to be in charge in any way, which is what’s happening now. “Now for the first time in American Catholic Church history, members of the laity are more educated than ever before, more accomplished than ever, more elite,” she said. “For most of U.S. history, the most accomplished people in the Catholic Church were the hierarchy. Now you have laity who are saying: ‘I wouldn’t run the church like this.’ ” Among the parishes where groups are organizing are two very large ones in the Arlington Diocese, known as one of the country’s most conservative. There are about 70 churches in the diocese, but the organized demand for internal reform is new. As are priests serving as neutral facilitators or supporters. Norman, who has taught Sunday school and served as a Eucharistic minister, is part of the group organizing at the 12,000-member Our Lady of Good Counsel Catholic Church in Vienna. Following several meetings about what could be done to demand repair from clergy, about 250 members of the affluent and diverse parish signed on to a parish-crafted petition made public a few weeks ago. The document includes a list of action items sent to all U.S. bishops with a letter. The signers, it noted “are here to help save our Church.” The three-page list calls for more transparency and authority for the laity, including a call for nonclergy to have a greater role in the selection of bishops, priests and seminarians. It called for an end to an all-male hierarchy. It called for all financial records and decisions to be open, including any payouts of abuse claims. The meetings and compilation of the document were well-publicized within Our Lady, and the Rev. Matt Hillyard encouraged those who agreed as well as those who did not to participate. This is a tightrope for Catholic priests, who seldom publicly criticize or challenge bishops, and the mere existence of the public document is controversial at Our Lady. Some felt allegations and criticisms being made this year against American bishops and cardinals — including two District leaders, Donald Wuerl and Theodore McCarrick — hadn’t been fully proved. Others felt giving laypeople authority over clergy would make the Catholic Church un-Catholic — or even Protestant. Hillyard asked the group not to refer to itself as the “parish” group but to take another name, which it did: the D.C. Area Catholic Action Group. The priest said he worked hard to encourage people with different views to write their own letters to the bishops. The priest said what feels new about this era is the scope of the abuse and mismanagement that is alleged in different scandals, including in Pennsylvania, where a grand jury this summer released a devastating report about abuse and a coverup. “This was different because it was bigger,” he said. “The problem has raised the issue of transparency. I don’t think it’s unhealthy. It’s just where that dialogue goes.” Our Lady is pairing in its organizing with St. John Neumann, a 4,000-household parish in nearby Reston. A group there worked for months this fall on various mission statements and drafts and careful rules for even speaking in their sessions. They began meetings with a prayer: “My God . . . help us to conduct ourselves during this time, in a manner pleasing to you. Amen.” More than 600 people at St. John signed a letter to the bishops with action items including a call for the church to stop lobbying against the repeal of statutes of limitations, to incorporate women into “every level” of decision-making, to stop excusing “criminal or abusive behavior” by referencing norms and protocols “acceptable in previous eras.” The St. John letter also calls on bishops to stop “scapegoating . . . the problem of sexual abuse is not related to homosexuality.” Hillyard isn’t the only one who approaches the new organizing with caution. Even the Catholics who are most passionate about reform can be wary. “I’m not sure I’d use the word challenge,” said Betty McFarlane, one of the leaders of the St. John group. Her husband, Tom, doesn’t hesitate. “It’s more a function of the degree of frustration among all Catholics. With the way the bishops have failed to address the issue over time.” It’s not clear how the bishops will react. Angela Pellerano, the spokeswoman for the Arlington Diocese, did not respond to several requests for comment for this article. A diocesan official who was scheduled to attend one of the opening meetings at Our Lady canceled the night before, and Bishop Michael Burbidge has held no open forums on the abuse issue this year — only ones that have been invitation-only, parish members said. The diocese has not posted a list of priests accused of abuse in the diocese but said earlier this fall that it will. Burbidge did respond to a copy of the document created by the Our Lady parishioners, writing Hillyard a two-paragraph letter that some congregants found disrespectful. “It is my hope that you have been faithfully sharing with your parishioners the many ways I have personally addressed the issues raised in the petition,” he wrote. Many of the most involved Catholics say they are still working out what they mean when they say they want more accountability. The nationwide effort, known as the 5 Theses, calls for “dismantling clericalism,” but McCloskey cedes that Catholics disagree on what that means. Give the laity authority over bishops? Have bishops and cardinals dress more humbly? “Some feel it’s overstepping boundaries or not respecting the good work of priests and bishops or their authority,” she said. “I don’t know if we all mean the same thing by ‘clericalism.’ . . . But what most people agree upon is that the distance between bishops in particular and the people of God has been too great.” Members at McCloskey’s parish, Holy Trinity in the District, have held a retreat in which the priest was a participant — not the leader. They have begun also hosting female Bible scholars who can discuss women’s role in scripture. The 5 Theses effort, which was started by members of Holy Trinity, St. Bartholomew’s in Bethesda and other D.C. area parishes, includes a website and an organized effort to place postcards with their demands and two affixed pennies in the Sunday offering basket, symbolizing the offering of their “two cents” and, for some others, expressing a plainly defiant donation. Despite such moves, Cummings and others who study American Catholicism agree that the recent burst of organizing, while historic, involves a small minority of U.S. Catholics. Most people who want change, Cummings said, are either quietly leaving organized Catholic life, or scaling back to just the spiritual — coming to Mass but going out the side door before coffee hour. Or simply praying that things change. Contact: michelle.boorstein@washpost.com

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.