|

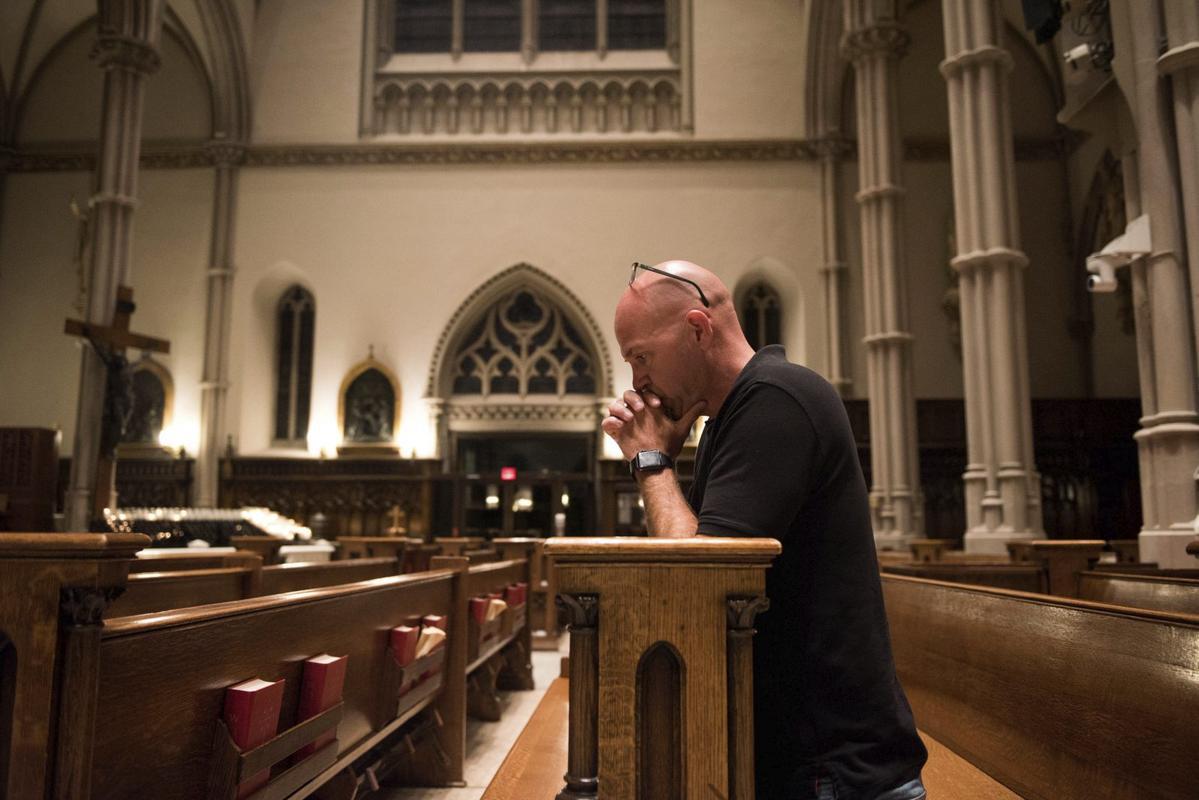

Can victim funds help heal wounds of Pa. church sex abuse scandal?

By Aaron Aupperlee

The 15-page packet of information John Delaney received in the mail weighed heavily on him. Inside was information about a fund set up by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia to compensate victims of sexual abuse at the hands of Catholic priests and an application to apply. "I'm not sure what I'm going to do. It's a hard pill to swallow," Delaney, 48, said in a telephone interview from his Sevierville, Tenn., home. Delaney, the first victim of sexual abuse to testify before the Philadelphia grand jury in 2005, could soon face a choice: Accept money from a compensation program that has paid out $25,000 to $500,000 to victims of clergy sexual abuse elsewhere — a tacit acknowledgment from the church that abuse occurred — but give up any chance of ever taking his claim against the church to court. Or he could wait on the Pennsylvania legislature to perhaps, one day, open a legal window for him to sue the church, to have his day in court, and potentially win millions. The compensation programs offer a chance to heal, bishops across Pennsylvania have said. But attorneys who have shepherded victims through similar funds elsewhere say the funds allow the church to settle claims of sexual abuse for less money and with less public exposure than if it went to court. They say the funds can insulate the church both politically and legally should lawmakers change the statute of limitations and allow old claims. "It's not about the church doing the right thing," said Jon Little, an attorney who has handled several similar cases in New York. Compensation coming to Pennsylvania Hundreds, perhaps more than a thousand, of others will face a similar dilemma as Delaney over the next several weeks as dioceses from Erie to Pittsburgh, from Greensburg to Scranton, establish similar compensation programs. Pittsburgh announced the details of its fund this month. It will start in late January. The funds are a way to provide money to victims barred from pursuing claims in civil court by the statute of limitations. Church officials announced the creation of compensation funds Nov. 8, just days after the Pennsylvania legislature adjourned without voting on a proposal to create a two-year retroactive window of opportunity for older abuse victims to file civil lawsuits. Pittsburgh Bishop David Zubik has called it the best option for recovery and healing. Greensburg Bishop Edward Malesic has said he prayed about the fund and feels it's the right thing to do. A spokesman for the Pittsburgh diocese said officials have not heard concerns about the compensation funds and are encouraged by the funds in other dioceses. The Greensburg diocese did not respond to requests for comment on this story. But Little, who represented U.S. Olympic gymnasts abused by former team doctor and convicted pedophile Larry Nassar, said the funds allow the church to pay off victims for less than they could win in court and silence them. Mitch Garabedian, a Boston-based attorney who handled some of the first clergy abuse cases in that city and has represented hundreds of victims in New York who applied to the compensation programs, encourages victims to approach the funds with skepticism. "Why would anyone trust what the Catholic church has to say at this point and time given their criminal history?" Garabedian said. Garabedian, who was portrayed by Stanley Tucci in the 2015 Oscar winning film Spotlight, said he has about 75 clients throughout Pennsylvania weighing their options. Harrisburg-based lawyer Ben Adreozzi, who represents about 75 clients, said around 90 percent of them are seriously considering applying to the compensation fund. Altoona lawyer Richard Serbin, who has represented about 300 victims of clergy abuse over the last 30 years, said many are seeking advice. Ryan O'Connor, a Verona man who was raised in the Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown and molested by a priest there, said he would reject any settlement offered to him. That diocese hasn't signaled it would establish a new victim compensation fund. It has paid $21.5 million since 1999 to settle claims of abuse. "I wouldn't even dignify it with a response," O'Connor said of a settlement the diocese might offer him. "Ultimately, my mindset is to be in a court of law with the predators. They need to see the damage they did to us, to our families, to our communities." The $25,000 to $500,000 payouts are far less than victims could win if allowed to take their case to court, attorneys and experts said. Jury verdicts in other, similar sexual abuse cases have awarded victims $11 million to nearly $30 million. Cash awards through compensation funds, in bankruptcies or through other ways, pay less. Marci Hamilton, founder and director of Child USA, a nonprofit calling for changes nationwide in statute of limitation laws including allowing old claims to come to court, said the payouts through victim compensations funds for child sexual abuse average between $200,000 and $1 million nationally. Victims of Catholic clergy abuse in California received on average $1.3 million when dioceses set aside nearly a billion dollars. Putting a dollar sign on abuse Kenneth Feinberg, a Washington attorney who has handled some of the largest settlement and compensation cases in the last two decades, will administer the victim compensation program for the dioceses of Greensburg, Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, Erie, Allentown and Scranton and the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, which announced this month that it had set aside $25 million for abuse victims. The firm is also handling five programs for dioceses across New York including the Archdiocese of New York and is working with dioceses in New Jersey on a compensation program. Camille Biros, the firm's business manager, won't say how much the funds have paid to victims or how much the dioceses have paid the firm. The Archdiocese of New York reported in August that it had awarded nearly $60 million to victims. The Diocese of Ogdensburg, NY, paid $5.5 million to 39 victims. "No matter how much money you give them, they're never going to get over this," Biros said of victims. Biros said the program in Pittsburgh will closely mirror what Philadelphia and dioceses in New York are doing. Biros is helping the Greensburg diocese design its program. Biros said the entire process typically takes less than 90 days. Nothing in the waivers issued in New York prohibit people who have gone through the fund from speaking out about their abuse, the compensation program or the amount of money awarded, Biros said. Victims who go through the Pittsburgh program will also be free to talk. There are some non-negotiable aspects of each and every program. Before anyone signs the final release , Biros requires people meet with an attorney. People can either hire their own attorney or Biros offers one at no charge. "We just don't want anybody to release their rights without fully understanding it ," Biros said. Biros also wants final say in regards to which claims the firm will accept and how much money to award. Silencing and intimidating victims Compensation programs that accept new claims, ones not previously reported to police or the diocese, require that both the person making the claim and the church report it to the district attorney, Biros said. Requiring the person submitting the claim to report helps guard against the rare bogus claims. Requiring the church report ensures that new claims will be investigated. Biros said very few claims are rejected. Nothing in the funds require the church to make public new claims or the names of new priests accused, Biros said. However, the Pittsburgh diocese said it would make public any allegations against a living or dead priest not already named. This still worries attorneys representing the victims. Little, the Indiana attorney who has handled cases in New York, said the programs allow the church to intimidate and silence accusers. Boston attorney Garabedian said it prevents the true depth and scope of the abuse and coverup from being known. "The Catholic church, by implementing these programs, is trying to sweep the matter under the rug once again, so the ugly truth isn't revealed," Garabedian said. Little and Garabedian said bishops use the funds to keep state legislatures from opening up legal windows for civil lawsuits. Past efforts to pass such laws in Pennsylvania have failed. Hamilton said she thinks dioceses are setting up compensation programs not to avoid windows for old claims opening, but because they know legislatures will soon adopt them. She expects at least eight states, including New York and Pennsylvania, to open statute of limitations windows in 2019. "The window is inevitable," Hamilton said. "They can settle out cases before they're dragged into court." A chance to heal Going through the legal system may be more than a victim can handle, Hamilton acknowledged. She called the fund process more humane than the courts. They are a good idea, she said, as long as the payments are fair and victims can choose whether to participate. Garabedian said the amounts paid out are inadequate. He calls the Catholic church a multi-trillion dollar corporation with money squirreled away and says it could pay more. Dioceses tell compensation fund administrators how much they are comfortable paying and that amount sets limits on how much victims receive, Garabedian said. In Pittsburgh, the diocese said it will fund the compensation program through past and future sales of property. In Greensburg, the diocese has not said how it will fund the program, only that it wouldn't be with money from the parishes. Dioceses in New York funded their programs through loans and self-insurance, money set aside to pay for insurance claims. The Archdiocese of New York sought a $100 million mortgage to finance its program. Biros said she does not allow diocese officials to set ceilings on the amount of money they are willing to pay. Officials can tell her they are comfortable with a certain amount and anything above that would be difficult and could lead to bankruptcy. But it isn't just about money, Garabedian said. "There isn't one victim I have represented who wouldn't give back all the money in the world if it meant the sexual abuse never occurred," he said. "It doesn't bring back a life stolen."

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.